Courtesy Nick Cooper

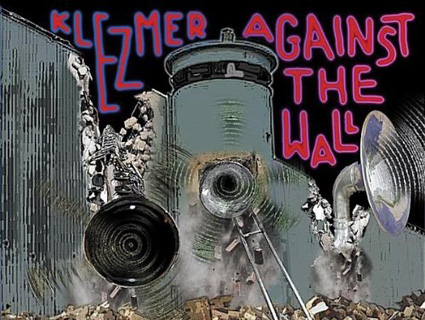

Nick Cooper, a 42-year-old Houston drummer of Jewish ancestry, conceived the idea for the 2010 album, Klezmer Musicians Against the Wall, while standing outside a Muslim punk rock concert in New York.

Cooper had spent the evening slamming to the music of the Kominas, one of many bands inspired by Michael Mohammad Knight’s portrayal of a fictional Pakistani punk-rock scene in his 2003 novel, The Taqwacores. “What if we did something like that?” he remembers thinking. “Maybe I could create an anti-occupation klezmer scene?”

Many Americans associate klezmer with Jewish weddings and bar mitzvahs. But the folksy, instrumental music from 19th century Eastern Europe has spawned diverse, creative offshoots, including Cooper’s band, The Free Radicals. Cooper says he was attracted to the “one-two beat” of klezmer music, which “kind of overlaps with punk-rock tunes.” The New Yorker describes his band as a “horn-heavy, continually evolving collective” that “produces a wildly eclectic fusion.”

Cooper was raised in a secular Jewish family, “has very little interest in religion,” and has never traveled to Israel. He celebrates some holidays, including Passover—because it’s about “standing with oppressed people of the world.” After forming in 1996, the Free Radicals have regularly performed at protests and charity concerts for liberal causes. They refuse to perform for projects sponsored by Israeli institutions unless those institutions are explicitly opposed to Israel’s 43-year occupation of the Palestinian territories. Cooper is also active in organizations that promote boycott, sanctions, and divestment from Israel.

After that Kominas concert, Cooper used a website called Klezmer Shack to contact hundreds of musicians around the world. Most ignored him. Others “cursed me out or sent me some kind of nasty message.” Still others declined to participate, but they engaged Cooper in “constructive debate that at least wasn’t insulting,” he says. In the end, about 30 bands expressed interest.

A heated debate then ensued over the album’s political message. Some musicians opted out as the bands attempted to compose a mission statement. The final version reads: “Klezmer Musicians Against the Wall oppose discrimination, injustice, and brutality against living beings. We support opposition to Israeli apartheid and occupation through non-violent protest, targeted boycotts, civil disobedience, and direct action. We encourage the international community to join us. Musicians know how people from different cultures can build bridges, not walls.”

The 14 remaining klezmer bands from the US, Israel, Germany, and the UK exchanged audio files over the internet and finished the CD in about two months of intensive work. They decided to donate their online sales proceeds to two charities teaching arts and music in the Palestinian territories, Project Hope and Middle East Children’s Alliance.

While the album is almost entirely devoid of lyrics, its political message is conveyed artistically. Cooper says that one song, “For a Hurried Funeral,” is meant to make listeners “think of all the people in the world who have to go to a funeral and get the hell out of there as quickly as possible, because if they don’t, they’re going to have their own funeral.” Another song, “Enemy Combatant Playground,” includes authentic voices of children playing in the Palestinian territories. The cover photo features the horn—a classic klezmer instrument—tearing through the wall separating Israel and the territories.

Some in the Jewish community are offended by the idea that traditional Jewish music could be used to rally protesters against Israeli policies in the West Bank and Gaza. The radio station Shalom South Florida banned all of the klezmer bands featured on the album, and the website Klezmer Shack declined to review the CD. These snubs reflect the sharp and growing political divides within the American Jewish community over the question of Israel’s policies towards Palestinians.

Yet Cooper is forging ahead with his plans for an anti-occupation klezmer scene. The album has been out for a year now, and sales are growing at a leisurely pace. Cooper is planning a promotional event in July at a Houston club, and another one in New York in September. “Whether your message comes through the lyrics, or through your artwork and the names of the songs,” he says, “there’s a really important place for all kinds of music in the world of activism.”

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones.