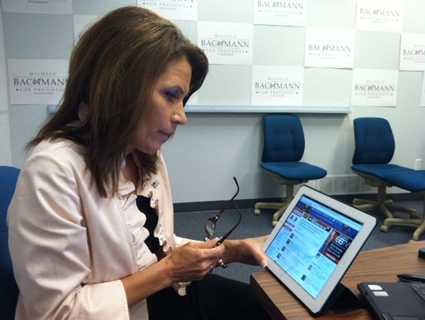

Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.).<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/5854180927/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

The first rule of Michele Bachmann’s presidential campaign: Don’t talk about Michele Bachmann. Matthew Spolar of New Hampshire’s Concord Monitor scored a sit-down with the Minnesota congresswoman and GOP presidential contender and reports that it ended abruptly when he asked her about the issue that definied her career as a Minnesota state senator:

Bachmann cut off an interview last week as she was being asked a question about gay marriage and emphasized that she is focused on rebuilding the economy and repealing federal health care reform.

“I’m not involved in light, frivolous matters,” she said. “I’m not involved in fringe or side issues. I’m involved in serious issues.”

This is a trend. Here’s the New Yorker‘s Ryan Lizza, similarly recounting how his one-on-one with the candidate came to end: He asked one too many questions about Bachmann’s ideological mentor, the theologian Francis Schaeffer:

As I started getting deeper into a conversation with her about Schaeffer, she abruptly ended the interview. She said she had to leave for an appearance on “Hannity” but would try to set up another time to talk. I didn’t hear from her again. Her press secretary later told me that Bachmann “wasn’t comfortable with the line of questions, and that’s why there wasn’t a follow-up conversation.”

Here’s Davenport, Iowa’s WQAD, detailing how it and other local stations were blacklisted by the campaign after they asked Bachmann about her Christian counseling clinic’s practice of “reparative therapy,” which seeks to cure gay people of their homosexuality:

The reporter asked a question about Bachmann’s clinic and her husband. At that point, McClurg says the staffer took the microphone off of Bachmann, tossed it to the reporter and said their interview was over.

Here she is last month at the National Press Club, in response to a question about whether she still believes homosexuality can be cured:

My husband is not running for the presidency, neither are my children, neither is our business, neither is our foster children, and I am more than happy to stand for questions on running for the presidency of the United States.

And here she is in June, dodging the same question from Bob Schieffer:

“You know, I firmly believe that people need to make their own decisions about that,” she said. “But I am running for the presidency of the United States. I am not running to be anyone’s judge. And that’s where I’m coming from in this race.”

You can decide for yourselves whether Bachmann’s refusal to answer questions she doesn’t like is a smart strategy. With the rise of conservative media, it’s certainly easier than it’s ever been, and it’s not as if the rest of us have especially long attention spans.

But horserace considerations aside, let’s just be clear: Michele Bachmann does not believe that gay marriage is a fringe or a side issue. If she did, she would not have signed the Iowa Family Leader’s Marriage Pledge in July, which committed her to opposing same-sex marriage at the national level (in addition to rejecting pornography and Islamic Shariah law). She would not have signed the National Organization for Marriage’s pledge just last week, which commits her to “appoint a presidential commission to investigate harassment of traditional marriage supporters.” She would not have raised money for the Minnesota Family Council in May, at a time when it was driving that state’s effort to ban gay marriage once and for all. She would not have gushed to her supporters in May about being the “tip of the spear” of the anti-gay marriage effort.

Critically, if Bachmann didn’t think gay marriage was a real concern, she would never have called it an “earthquake issue” that could destroy civilization as we know it, and she would not have compared Massachusetts’ decision to legalize gay marriage to Pearl Harbor. (Both of things sounds pretty serious!)

Bachmann’s in a tough spot. Her path to the GOP nomination depends on her ability to carry Christian conservatives who, like her, believe that America has strayed from its Judeo-Christian foundations. That, as Lizza ably explains, has been the guiding principle behind her entire political career, and her greatest selling point. It’s at the root of Bachmann’s opposition to big government, which she believes jostles with God for our hearts and minds in public schools; it was the thesis touted by Schaeffer, the theologian she says changed her life. But most Americans don’t see a United Nations conspiracy when they go shopping for light bulbs, and according to the latest surveys, they don’t see anything wrong with allowing two men to get married.