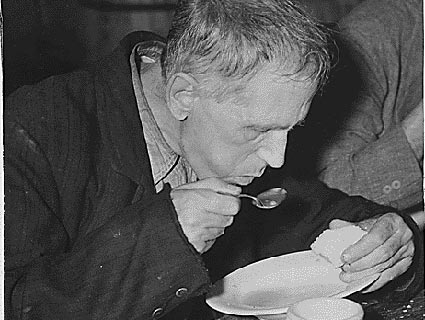

WPA photo from Depression-era soup kitchen.Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/pingnews/">pingnews</a>

Among the latest attacks on President Obama’s policies are claims that his economic stimulus created few jobs, and at exorbitant cost to taxpayers: $278,000 per job, to be exact. Fuzzy math aside, what his foes fail to mention is that the stimulus, like all else these days, operated under the conservative creed that everything must be done through the private sector. This ethos, which Obama has firmly embraced, prevents the federal government from taking the far more efficient route of simply employing people, which might have created many more good jobs at the same cost.

Had Obama had heeded FDR’s experience during the Great Depression, we could have put unemployed people to work rebuilding American infrastructure—bridges, tunnels, railroads, roads—not to mention restoring and shoring up wetlands and carrying out other environmental projects. That’s what Roosevelt famously did with his Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps.

Such an initiative might have been possible, on some scale, prior to the midterm elections. But with the gridlock in Congress and diminishing confidence in the president and government, that course now is hard to imagine. Instead, the austerity imposed by the debt deal will further impede any chance of real job growth—as Roosevelt discovered in 1937 when he briefly adopted austerity measures, only to see a falling unemployment rate spike once again.

But even at this dismal stage, there remain a handful of realistic projects that ought to appeal to some fiscally minded conservatives, and Democrats as well.

Jonathan Alter, a journalist and historian of FDR’s New Deal, is promoting an idea that would allow states to “convert their unemployment insurance payments from checks sent to the jobless into vouchers that can be used by companies to hire workers.” The amount of the checks would in effect become subsidies to the employers, so that “for instance, a position paying $40,000 might cost employers only $20,000, thereby encouraging them to hire…If a mere 10 percent of unemployed Americans persuaded employers to accept such vouchers, more than a million people would find work with no new spending beyond some administrative costs.”

Alter thinks this plan, first suggested by Alan Khazei, a Democratic candidate for the Senate in Massachusetts, might appeal to “a Republican House that loves the concept of vouchers.” But so far there’s been no interest from Congress or the Obama administration.

Another option is the already much-discussed German experience with short work weeks. As Kevin A. Hassett of the American Enterprise Institute explained this scheme back in 2009:

Firms that face a temporary decrease in demand avoid shedding employees by cutting hours instead. If hours and wages are reduced by 10 percent or more, the government pays workers 60 percent of their lost salary. This encourages firms to use across-the-board reductions of hours instead of layoffs. Here’s how the program works.

A firm facing the challenges of the recession cuts Angela’s hours from 35 to 25 per week, thus reducing her weekly salary to 714 euros from 1,000 euros. Angela does not work for the firm during those hours. As part of its short-work program, the government now pays Angela 171 euros—60 percent of her lost salary. Most important, she still has a job. Effectively, the government is giving her unemployment insurance for the 10 hours a week that she is not employed.

Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) have put this program into legislation that so far has gone nowhere, with only a handful of cosponsors. This despite the fact, per Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, that “21 states (including California and New York) already have short-time compensation as an option under their unemployment insurance system. In these states, a governmental structure already exists to support work sharing, although there would have to be changes to make the system more user friendly so as to increase take-up rates.”

In the Washington Post last week, Steven Pearlstein pointed to another way of immediately putting people to work, which harkens back to the idea of rebuilding the nation’s crumbling infrastructure:

Over the next decade, the federal government is slated to spend hundreds of billions of dollars building roads, schools, airports, trolley lines and airport terminals, modernizing the air traffic control system, replacing computer systems and buying planes, ships, tanks, trucks and cars. Moving up some of that spending from years 8, 9 and 10 to years 1, 2 and 3 won’t cost any more in the long run, or increase the long-term deficit any more, but could sure help put a floor under the economy in the short run. For those worried about pork, the actual spending decisions could be left to an independent Infrastructure Bank.

To spur private investment in equipment and research, the government could immediately allow companies of all sizes to deduct 100 percent of such expenses made in the next three years, rather than “depreciating” them over many years. That incentive to invest now will increase the deficit in the short run but have little or no impact on the long-term deficit.

As former MoJo reporter Suzy Khimm writes in the Post, “The question of infrastructure funding will come up as soon as Congress returns from its August recess,” since “a bill reauthorizing spending on surface transportation—which would help build roads, highways, and the like—is set to expire in September. There’s a big gap between the House GOP proposal, which would slash federal spending to 35 percent less than Fiscal 2009 levels, and Democratic Sen. Barbara Boxer’s two-year plan to spend $55 billion a year. Boxer’s proposal would require revenue beyond what’s in the Highway Trust Fund, which receives money from the gas tax, promising yet another fight over which will be better for the economy—reducing the deficit or Keynesian spending on infrastructure.”

We all know how that fight is likely to turn out. And as Alter notes, even these modest approaches to job creation call for an attitude of what Roosevelt called “bold, persistent experimentation”—and the leadership to back it up. And as we’ve seen all too clearly, Obama is no FDR.