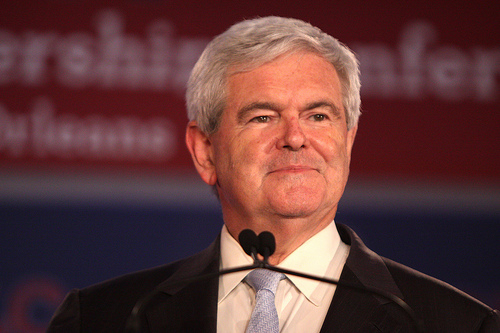

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/5438140228/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

We are officially in the midst of a Newt Gingrich boom.

You didn’t notice? ABC News, pointing out that the former House speaker has leaped to third place in the GOP 2012 contest with 10 percent support in a recent poll, reported, “For Newt Gingrich, the tides seem to have turned.” The Washington Post‘s political über-junkie Chris Cillizza wrote: “Don’t call it a comeback! Actually, do. Sort of.” He notes that a series of decent debate performances have vaulted Gingrich, whose campaign has been marred by profound disorganization and embarrassing revelations about Tiffany’s expense accounts, into the tier between top-tier and second-tier, behind Herman Cain and Mitt Romney. So with the Newt rehab underway, it may be an opportune time to ask: Is Gingrich too mean to be president?

Gingrich is by far the nastiest of the pack. Last spring, Tim Murphy and I posted a compendium of the highlights—or lowlights—of his three-decades-long career of rhetorical bomb-throwing. From the moment he was first elected to Congress in 1978, Gingrich has made mudslinging a specialty. He has routinely compared opponents to Nazis or to Nazi appeasers. (It can be confusing.) He has counseled fellow Republicans to accuse Democrats of treason. Last year, he derided President Obama for being “fundamentally out of touch with how the world works” and asked, “What if [Obama] is so outside our comprehension that only if you understand Kenyan, anti-colonial behavior, can you begin to piece together [his actions]? That is the most accurate, predictive model for his behavior.”

Gingrich has always draped fierce opposition in poisonous maliciousness. That has usually not been a recipe for success in presidential politics. For most political consultants and observers, it’s an article of faith that voters tend to embrace optimistic and sunny-side presidential candidates, even when times are tough. Has there been a mean president? Not since Richard Nixon—and he generally kept the depths of his pathological vileness (such as a plan to firebomb the Brookings Institution) out of the public view. Jimmy Carter was a touch dour, but not vicious. Reagan did mean things—such as firing the air traffic controllers and backing death-squad-connected leaders in Latin America—but always with that Hollywood smile. George Bush the First exuded a Republican noblesse oblige. Bill Clinton was a good ol’ boy policy wonk. Bush the Second, it was said, was the sort of fellow you’d want to have a beer with (except for maybe during his mean-drunk days). Obama is nothing if not well mannered.

The general-election presidential candidate of recent years who came closest to being outright mean was Sen. Bob Dole in 1996, and that was mainly because he had a sharp and acerbic sense of humor that played better on the Tonight Show than on the campaign trial. John McCain in 2000 was joyous as the maverick challenger to Bush II during the primaries, though in 2008, as the GOP nominee, he was a bit on the grumpy side. Pat Buchanan’s presidential runs, fueled by a populist-tinged sense of vengeance, fizzled.

Harsh and cruel have generally not worked for national candidates. (Spiro Agnew, Nixon’s veep, is another exception, and it didn’t end well for him.) When Gingrich entered the race this year, it seemed possible that he would try to pull in his claws and attenuate his inner malcontent—even if the Republican electorate was in a foul mood. Yet Gingrich has stayed bombastic and grinch-ish.

In a debate earlier this month, he noted: “There’s a stream of American thought that really wishes we would decay and fall apart and that the future would be bleak so that the government can share the misery. It was captured by Jimmy Carter in his malaise speech. It’s captured every week by Barack Obama in his apologias disguised as press conferences.” Really? Obama wants the United States to collapse? (That must be why he bailed out the auto industry.) There’s not much in this statement that makes sense. It is just a mean-spirited shot.

Such foul rhetorical excess flows readily from Gingrich’s never-depleted reservoir of bile. At a Republican gathering in June, he called Obama “the opposite of freedom.” Was he saying Obama is a dictator? Not quite. He denounced the president as “a natural secular European socialist.” But that’s apparently the functional equivalent of a Stalin-like tyrant.

Gingrich is, of course, particularly hard on secularists and the left. In a recent debate he pounded atheists and agnostics: “How can you have judgment if you have no faith? How can I trust you with power if you don’t pray?” He slammed the Occupy Wall Street protests for including a “frightening level of anti-Semitism.” Not long ago, he contended that liberals are “fundamentally wrong” about “the nature of America.”

In the Republican debates of recent weeks, Gingrich has at times endeavored to position himself as being above the petty bickering of the other candidates (namely, Rick Perry and Mitt Romney). This week, he earnestly claimed that he believes that “policy dialogue, handled with civility, is exactly what politics should be.” Yet he has frequently tossed aside respect to make room for low blows.

Among GOP voters this season there does appear to be a desire for an I-feel-your-anger candidate who is willing to say anything (as long as it’s ugly) about Obama. Thus, there was the rise (and then fall) of Donald Trump, who banged the birther drum, and of Michele Bachmann, who once suggested that Obama held “anti-American” views.

None of the 2012 GOPers are soft on Obama and the Democrats (except for Jon Huntsman, who used to work for Obama). But most successful politicians find a way to slam the opposition without casting themselves as malevolent SOBs. In this race, Romney is trying to be the responsible chief executive. Perry is attempting to be the tough-talking sheriff. And Cain, the feisty pitchman. Each of these strategies is rooted in the history of the candidate. But can Gingrich’s turn his long-established mean streak into an asset that helps him vanquish these other contenders and defy history in the primary contests and then the general election? If so, he would certainly give new meaning to the so-called bully pulpit.