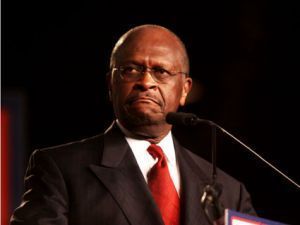

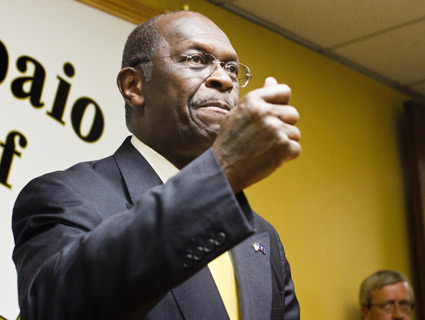

As he’s climbed into contention for the GOP presidential nomination, Herman Cain has relied on a campaign staff as unlikely as the candidate himself. There’s Mark Block, the chain-smoking, mustache-sporting chief of staff who was once banned from working on elections in the state of Wisconsin. There’s Rich Lowrie, the economic adviser who devised the 9-9-9 plan while employed at a Wells Fargo in Pepper Pike, Ohio. And there’s J.D. Gordon, a former Department of Defense flack at Guantánamo Bay, who once accused a female investigative reporter of sexual harassment.

But the most curious Cain staffer is one you’ve probably never heard of. Jamie Brazil is the vice president of field operations for Cain’s campaign. He’s also godfather to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s nephew, a onetime consultant to ex-Iraqi Prime Minister Ayad Allawi, and a political operative who came under FBI scrutiny during a mammoth pay-to-play scandal that roiled Philadelphia’s political world.

A long-haired attorney from Scranton, Pennsylvania, with a passing resemblance to the The Dude, Brazil built a reputation for himself in the ’90s as a political consultant adept at winning elections and making connections. A longtime friend described Brazil to the Philadelphia Daily News in 2004 as “a man who could talk a dog off a meat wagon.”

His political contacts made him a good fit in the lobbying world, and in March 1998 Brazil took a job with Commerce Capital Markets, a Philadelphia-based corporation that was just breaking into the municipal bond market. Brazil was tasked with securing contracts with Pennsylvania cities.

But there was a hitch: In his two years with Commerce, and four subsequent years in the same role at Hefren-Tillotson Inc., Brazil never obtained a license to sell municipal bonds, nor did he ever pass the required Series 52 test to work in the securities field. That’s a violation of industry standards.

In 2005, a routine inspection of Commerce Capital’s record by the National Association of Securities Dealers, the industry’s regulatory board, revealed that Brazil had been acting as an “unregistered” securities dealer. When the NASD—which is now known as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority—asked Brazil to provide documentation on his dealings, he refused to cooperate. As the regulatory board’s decision notes (PDF), “Throughout these proceedings, Brazil has asserted his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination as his only defense.”

Brazil’s punishment was the most severe the regulatory board doles out to individuals. Having offered no defense or explanation for his actions, he was barred from associating with any securities firms—and docked $1,152.65 in hearing costs to boot. Brazil, who left Hefren-Tillotson in 2004, a year before the NASD rendered its verdict, has never appealed the decision.

The NASD investigation came at came at a critical moment for Brazil and his former employer, Commerce Capital. As Will Bunch has reported, both were both key players in a federal investigation into systematic pay-to-play corruption in Pennsylvania politics.

Commerce Capital had jumped into the municipal bond market with a vengeance in the late ’90s, and while Brazil was in its employ the company established itself as the dominant underwriter in the region. But its rapid ascent had raised concerns among industry observers, and ultimately, prompted a slew of state and federal investigations. As the trade publication Bond Buyer reported, from 1999 to 2003 Commerce Bancorp, an affiliate of Commerce Capital, donated $2.4 million to politicians in New Jersey and Pennsylvania—coinciding neatly with the Commerce Capital’s rise as the preeminent lender in the area.

Bond dealers are forbidden from contributing to political campaigns, but the NASD alleged that Commerce Capital had for years skirted that rule by funneling donations through Bancorp’s PAC. The company never admitted wrongdoing, but in 2005 it agreed (PDF) to a “a censure, $600,000 fine, and making a future certification to the NASD about procedures for compliance.” (The inquiry was unrelated to the Brazil investigation.)

It was around that time that Brazil’s work as a bond dealer—and the murky underworld of Philadelphia politics—came under scrutiny by the FBI, which was investigating corruption in Philadelphia’s City Hall. The feds zeroed in on key allies of the city’s Democratic mayor, John F. Street, charging that they had used municipal bonds and other city contracts for personal gain.

Among those prosecuted by the Justice Department was a Brazil associate named Shamsud-din Ali. A powerful Philadelphia imam and businessman, Ali had ties both to Street (he served on the mayor’s transition team) and the mob (his nickname was “Cutty”). Ali, the Justice Department alleged, had attempted to extort businesses seeking city contracts and bribed competitors to ensure his own businesses got a piece of the pie.

Brazil hoped Ali’s ties to high-ranking officials would open up business opportunities in Philadelphia for his then-employer Hefren-Tillotson; Ali, in turn, relied on Brazil to introduce him to new contacts. When FBI wires caught Ali meeting with the mayor of Scranton in 2001, Brazil was in the room. (The mayor was not accused of wrongdoing.) In another conversation, taped by the FBI, Brazil said to Ali, “I’d like someone to be able to say to [Street]: ‘H-T needs your help.'” (He was referring H-T Capital Markets, a Pittsburgh-based division of Hefren-Tillotson.) Brazil also served as the liaison (PDF) between Ali and Louis DeNaples, a casino owner who landed in prison for perjury over his ties to the Bufalino crime family.

Ali was ultimately convicted of racketeering, bank fraud, and extortion. Commerce Capital, following an Securities and Exchange Commission investigation, saw two high-ranking Commerce executives indicted for their involvement in the Philadelphia corruption scandal. That same year, the company announced it was exiting the municipal bond market.

Brazil’s involvement in the City Hall investigation makes him an odd choice to help lead a campaign that’s billed, at least by the candidate, as a break from traditional politics. (Cain, for his part, has ripped into the Obama administration for “crony capitalism.”) What makes his role even more unusual is that, for most of his life, Brazil has been a Democrat. And not just any Democrat—a close friend of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s family.

Hillary’s brothers have owned a lake house in the Scranton area for years and Brazil, who grew friendly with the Rodhams, was an early recruit for Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign. With Tony and Hugh Rodham, Brazil crisscrossed the state in a Winnebago to drum up support for Clinton, according to the Daily News. They stayed close over the years. Brazil became the godfather to Hillary’s nephew, and when the New York Senator ran for president in 2008, Brazil began helping out behind the scenes.

Angry that Clinton had lost out on the nomination to then-Sen. Barack Obama, Brazil took a paid position as the national director for Citizens for McCain, a nominally independent effort to support the Arizona senator created by Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.). Brazil hosted a dinner party at his house for Tony Rodham and McCain surrogate Carly Fiorina, along with Lynn Forester de Rothschild. They were the PUMAs, short for “Party Unity My Ass.”

Since then, Brazil has mostly worked with Republicans, although he’s stayed close enough to the Clintons. He credited Bill with connecting him with Allawi in 2010, whose party, as the Pottsville, Pennsylvania, Times-Tribune reported, Brazil helped maintain control of parliament.

Brazil, contacted through the campaign, did not respond to requests for comment. But in October, he told the Times-Tribune he had personal reasons for supporting Cain. “I like his jobs plan, I like him as a person,” he said. “This guy’s special. He’s got the X factor.”

Cain must think the same of his controversial campaign operative.