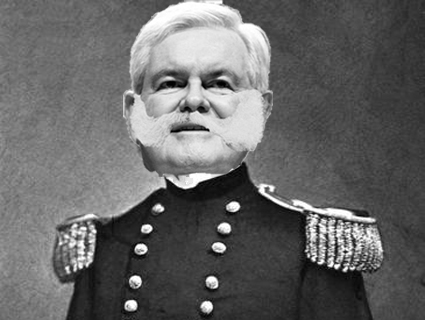

With the help of scientific advancements, historians have been able to figure out exactly what Ambrose Burnside would have looked like if he had Newt Gingrich's head.Gage Skidmore/Flickr; Library of Congress; Photo Illustration by Tim Murphy

There are no sex scenes in Newt Gingrich’s latest novel, The Battle of the Crater. This is for the best. It’s not because Gingrich is squeamish about the subject: In his 1995 beach read, 1945, the Germans invade Tennessee and a Nazi “kitten” seduces a White House aide. But a novel about a Civil War battle that turned into a racial massacre is a terribly awkward place for lovemaking, and, anyway, the former House speaker and current front-runner for the GOP presidential nomination has enough trouble getting his history right.

Gingrich has risen in the polls over the past four weeks while maintaining the traveling salesman routine that had previously made him a punch line. Since entering the race in May, he has released a new documentary about American exceptionalism, hawked DVDs about Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II, and toured the country to promote his wife’s children’s book about a time-traveling elephant. Now, on top of all of that, he has published Crater, his 26th book and the ninth coauthored with William R. Forstchen, a faculty fellow at Montreat College in North Carolina.

The Battle of the Crater explores the 1864 battle of the same name outside Petersburg, Virginia, in which Gen. Ambrose Burnside tried to break through Rebel lines by building a tunnel under the Confederates’ position and filling it with explosives. That part worked, somehow, but the subsequent assault was an epic disaster, ending with Union forces trapped inside the 30-foot-deep crater as mortars rained in. At a critical point in the fight, the Yankees sent in a division of black soldiers; after they were pushed back, the Confederates ignored pleas for surrender and started killing blacks indiscriminately. America was the loser.

The novel is intended in part to honor the black regiments that saw action at the Crater and help correct the narrative that says they cost the North the battle. (In fact, they nearly won it.) But in correcting one narrative, it whitewashes another, because none of the rebels we meet in Crater carry with them much animus to black soldiers. The only Confederate we see in any level of depth is a former journalist who, as a matter of principle, never owned any slaves. Our rebel points out, accurately, that not all black POWs were murdered—but that’s sort of splitting hairs when you consider that battlefield accounts describe white Confederates bashing in the skulls of surrendering and wounded black soldiers “like eggshells.”

Instead, the authors veer in the other direction. Gingrich and Forstchen even craft an imaginary scene in which General Robert E. Lee, the embodiment of Southern honor, instructs his subordinates to make clear that black soldiers at Petersburg are to be treated like any other opponent. But there’s no historical evidence that Lee gave any instruction of the sort. Nor did Lee intervene in the immediate aftermath, when his army pushed to return black POWs to their former masters.

It’s a significant omission, because just as the inclusion and heroism of black soldiers reflected the higher principles behind the Union effort, their slaughter and return to captivity underscored the moral depravity of the Southern effort. Black soldiers presented an existential challenge to white soldiers—slave owners or not—because they subverted the structure of white supremacy at the core of the fledgling nation. As historian Richard Slotkin has written, “The summary killing of armed Blacks and their White abettors was the logical extension of the slave codes that governed their society.”

You don’t have to read as far as the massacre to deduce the battle’s appeal for Gingrich, though. It’s clear he has a soft spot for Burnside, the Union commander. In Crater, the general comes off as a brilliant-but-misunderstood ideas man who locked horns with a corrupt and entangling bureaucracy. Burnside was a futurist of sorts, anticipating the kind of bunker-busting initiatives that would be commonplace come the First World War. If all went well at Petersburg, he might have ended the war. But he had no patience for bureaucracy.

Gingrich hates bureaucracies with the fierce passion he normally reserves for cable news anchors who ask him follow-up questions. And in the Army of the Potomac, circa July 1864, he has found a bureaucracy worthy of his scorn. If any organization could have used some Lean Six Sigma, it was this one, a mammoth fighting unit manned at every level by shell-shocked officers, alcoholics, political favorites, and glory-seekers. At the Crater, red tape, bad communication, and poor management cost hundreds if not thousands of additional lives.

The problem with this framing is that in scrutinizing the Army’s dysfunction, Gingrich ends up as a Burnside apologist. It’s a natural conclusion for someone who has spent his career churning out big ideas while bashing big government: If only Burnside’s plan had been adopted exactly as he’d specified, Gingrich suggests, the war might have ended then and there; the blame for the ensuing disaster (contra the historical narrative) lies largely with Burnside’s superior, George Meade. Newt even conjures up some super-secret missing cables, revealed to Lincoln by a rogue journalist who doubles as a spy, that purport to make that exact point. (In the book, Lincoln is sympathetic to that view, but keeps it secret for political reasons.)

Burnside’s idea may have been a good one in the abstract, in the sense that vaporizing your opponent’s front line is almost always beneficial. But ultimately it was a roundabout road to disaster, like putting a military-grade tank in the hands of your county sheriff’s department.

Gingrich’s book is not a total waste. The Battle of the Crater tells an interesting story and goes down smooth in a Dan Brown sort of way. The 38th United States Colored Troops, unfairly maligned by their contemporaries and largely forgotten by history, are well deserving of the former speaker’s attention. But the book also confirms something that Freddie Mac and Beltway insiders have known for a while: Only a fool would pay Newt Gingrich for his historical analysis.