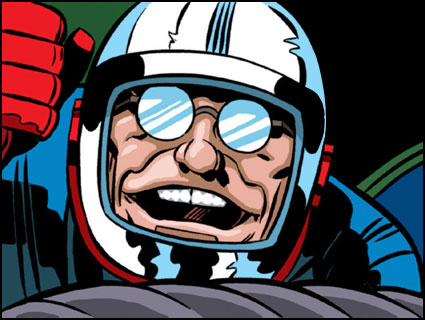

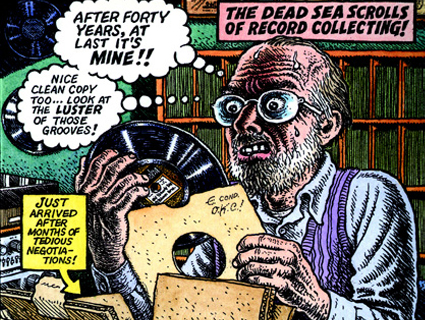

Detail from The Complete Record Cover Collection by R. Crumb © 2011 by Robert Crumb. Used with the permission of the W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Don’t go bothering Robert Crumb. The renowned cartoonist and American expat lives somewhere in the south of France, but when I call him to talk about his latest book, he steadfastly refuses to tell me where: “I don’t want people coming here looking for me,” he says, “so I don’t tell the name of this town.” He won’t elaborate on whom he might be hiding from, but it’s easy to believe that Crumb, 68, has a cult following. Over his nearly lifelong career, this icon of 1960s underground comics has created beloved characters like Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural, was the subject of a Terry Zwigoff documentary, and even illustrated the book of Genesis. (“First I was gonna make a satire,” he told me. “But the original text is so strange by itself you don’t have to satirize it.”) In 1991, Crumb was inducted into the prestigious Will Eisner Hall of Fame. Maus creator Art Spiegelman has called him “a monolithic presence, who rewrote the rules of what comics are.”

But behind the overt sexuality and anti-establishment riffs that characterize Crumb’s comics, his muse has always been old-timey American blues. He’s a die-hard collector of 78 rpm records from the likes of Memphis Minnie and Robert Johnson. Crumb himself is an accomplished banjo player, and made a splash in the 1970s underground folk music scene with his Cheap Suit Serenaders. He began drawing album covers and cartoon portraits of musicians while living in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood during the 1960s, and has since created an extensive portfolio of illustrations of classic rock figures like Janis Joplin, his old blues heroes, and his own band. This week WW Norton releases The Complete Record Cover Collection, a compendium of Crumb’s greatest music cartoons and album covers. I spoke with Crumb about trading records for art, Janis Joplin’s fatal quirks, and getting the hell out of the United States.

To view a selection of art from the book, check out our slideshow.

Mother Jones: When I was a kid, one of my best friends had the Big Brother and the Holding Company record you illustrated on his wall. And now, I can’t ever hear that band without visualizing that record cover. I wonder if you could talk about the relationship between an album’s cover art and the music on the album?

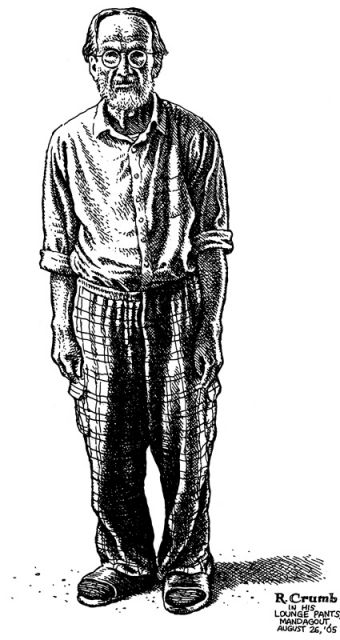

Crumb’s self-portrait: Courtesy WW Norton & Company

Crumb’s self-portrait: Courtesy WW Norton & Company

R. Crumb: Geez, I don’t know, all I can tell you is that when I did that cover for them, it was very short notice. They needed it fast, because they didn’t like the cover that CBS Records had done for them. So they came to me and said, “Crumb, we want you to do a cover for us but we need it, like, tomorrow.” So I pulled an all-nighter. I took amphetamines and stayed up all night, and did the cover. And I had never heard any of the music! I had heard them play at one of those ballrooms in San Francisco, the Fillmore or something. But I wasn’t particularly familiar with the tunes on that record, so I just kind of made up the artwork.

MJ: Without having heard the album?

RC: Yeah, that’s right.

MJ: That’s funny, because a listener’s first encounter with the album is so often the cover art, and it can have a big impression on how people hear the music. What do you think?

RC: Geez, it never affected me that way, particularly. But I’m into old-time music, I’m not very interested in modern, popular music at all. And if I’m really into some particular old-time musician, some fiddler or banjo player, I’m always dying of curiosity to see what they look like. So there’s some connection between visual images and music. But there’s plenty of old records where I have no idea what the band looked like, or even what sort of context the music was played in. I do covers for CDs and LPs of music that I like, reissues of old-time music, and then I’m inspired to make some kind of drawing based on this love of the music. I don’t do album covers or CD covers for groups or musicians I don’t like or have no interest in. But I liked Janis Joplin’s singing. She was a talented singer, I thought, but I didn’t think that band was very good, and I didn’t like that kind of music very much.

MJ: How’d you get interested in doing music-related work, in addition to your other stuff?

RC: Well, after that Big Brother cover, which was kind of a fluke, I got work from a small company in New York that was reissuing the kind of music I like. And this guy asked me to do album covers, and offered to give me old-time blues 78s in exchange—you know, the original records. So I jumped at that. Those records are hard to find, and this guy was very wealthy. He was a guy that if anybody had rare blues records they wanted to sell, they went to him, because he would pay money for them. He had lots and lots of duplicates, because he was a collector himself of these old 78s. So I did lots of covers in exchange for 78s—and you know what, I’m still doing that today. I’ve done several illustrations recently for reissues, in exchange for 78s.

MJ: Do you remember any one record in particular you got back then that you were really excited about?

RC: Well, lots of them. I was thrilled to get 78s by Blind Lemon Jefferson or Memphis Minnie or Charlie Patton. I couldn’t believe when that guy gave me Charlie Patton 78s in exchange for doing artwork for him. That was thrilling, God damn! Those are quite a find. You could look your whole life and never find those out in the field, looking out in secondhand stores or flea markets. He had probably the best collection of blues 78s in the country back then, and his shelves of duplicate copies were better than my collection. If I’d known then what I know now, I would’ve been a sharper bargainer and made him give me more records for the artwork. But I was very young, and I was so eager to get the records, I think he really took advantage of me.

MJ: Maybe you would’ve spent whatever money he gave you on records anyway?

RC: No, if I got money, I had to live on it. Even back then, Charlie Patton records were going for $50 or $100. I couldn’t afford to pay that for old records just to feed my obsession. I still can’t spend a lot of money on records at collector prices. There’s something in me that just won’t allow me to do that. But I will trade my artwork, which I know is worth thousands of dollars.

MJ: Could you tell me more about the time you spent living in San Francisco? What kind of relationship did you have with the musicians you did artwork for?

RC: Well, I really didn’t work for any other musicians after Janis Joplin. I did that first Big Brother cover because I really needed the money. I got 600 bucks, and in 1968 that was a lot of money for me—big money. And I kinda knew Janis Joplin. She liked the underground comics. She used to come around and hang out a little bit; she thought the comics were funny and all that. And she was a nice person, even though she drank too much. And then when she got really famous later, she was just surrounded by these sycophants, and it was just awful what happened to her. She just became more and more into drugs and alcohol, and accidentally killed herself.

MJ: So even though you weren’t that into the band, you made an exception because you needed the cash.

RC: Yeah, I suppose it sounds kind of crass. But you know, I draw the line at some things. Some things I won’t do for any amount of money. Like for instance, there’s a couple of CEOs of very large corporations that offered me lots of money to do special pictures for them. And I just refused to do that. Even if it was a million dollars I wouldn’t do it.

MJ: Why not?

RC: Because then you’re just like a servant to the rich. That’s so demoralizing and goes against every principle that I hold, you know? It’s like, okay, they can buy me because I’m a talented guy. They can buy talent. You can’t buy it for yourself, but you can buy other people’s talent to serve your purposes. And once an artist does that, he becomes like a plaything of the rich. You know, some of these wealthy collectors have paid lots of money for artwork that I already did, but I didn’t do it with the intention of catering to them. I think part of the reason my work is attractive to people like that is because it doesn’t cater to them.

MJ: I read on your website that one reason for going to France was that you had become disgusted with America. What do you mean by that?

RC: Well, the corporatization of culture. We lived in inland California, the Central Valley, and we witnessed over a period of 20 years of this invasion of shopping malls and corporate businesses and everything, and it lost all of its old character. Any kind of authentic character that it had was rapidly getting lost. The expanding urban development was just horrible to behold.

MJ: Have you been following Occupy Wall Street at all?

RC: Oh yeah, it’s great stuff. I think they should stay there, and persist and persist until they have some effect. I don’t know what effect they can have. I was thinking about it last night, I was laying in bed, thinking, “Can this thing have any effect on the wealthy establishment?” They’re so entrenched, they’re so powerful. I don’t know if they even care that people go there and demonstrate. What will it take, an armed revolution? That’s violent, and I’m kind of against violence. Violence begets violence, and then you get leaders who are violent men. And you don’t want that. You don’t want some Stalin in there as your left-wing leader. But it’s a great thing to see. I kinda thought that the American youth were very complacent and indifferent about all that, or just didn’t know what to do. But somebody got this thing going.

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones. And see below for interviews with other comics luminaries.