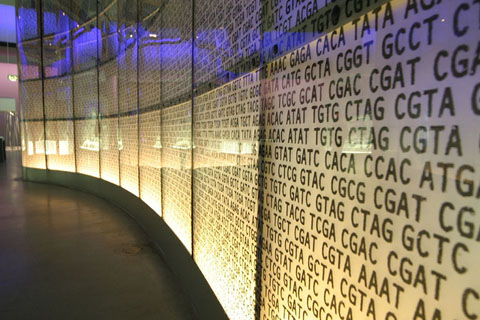

This DNA sequence can be found at the Science Museum in London.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/johnnieb/17200471/sizes/z/in/photostream/">JohnGoode</a>/Flickr

The human genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 are pretty notorious. A woman carrying a harmful mutation in either of these two genes is five times more likely to develop breast cancer in her lifetime, up from a 12 percent likelihood in the general population to about 60 percent. Taken together, mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 represent the single largest known hereditary source of breast cancer today. But so far, their notoriety has been limited to two usually disparate communities: scientists and patent lawyers.

That’s because BRCA1 and BRCA2 are essentially “owned” by a private company, Myriad Genetics, and are at the center of a two-year legal battle over whether human genes can be patented in the first place. Though always surrounded by controversy, gene patents are not uncommon; more than a quarter of human genes currently have patent-holders in universities and biotech companies across the US. But last Wednesday, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) finally petitioned the Supreme Court to rule on whether this is a legal practice at all.

The effects of a ruling against Myriad would be enormous. Currently, in order for women to get tested for potentially dangerous abnormalities in BRCA1 or BRCA2, they must shell out over $3,000 for the Utah-based company’s patented BRACAnalysis test. Because Myriad owns the patent on these two genes, other potentially cheaper testing options simply can’t exist. Many people, from within both the scientific and legal communities, have argued that this is true across the board; gene patents can limit the extent of research and raise the cost of treatments for patients.

The ACLU’s petition last Wednesday (which represents medical associations, geneticists, genetic counselors, patients, and breast cancer groups) came after two years of tug of war in the lower courts over the issue of whether Myriad’s gene patents cover preexisting “products of nature”—which the United States Patent and Trademark Office would deem unpatentable—or whether they have truly produced novel inventions.

The issue boils down to semantics. Each cell in your body carries a copy of these genes, which are reproduced each time a cell divides. Though the genes themselves are a natural product of your biology, Myriad has claimed that their contribution of isolating the gene is what differentiates it from a natural product.

“Simply because I have taken gold out of a stream, washed off the dirt, and made it shiny doesn’t mean that I deserve a patent on gold,” said Daniel Ravicher, president of the Public Patent Foundation (PUBPAT), one of the plaintiffs against Myriad, in a PBS-Frontline interview in April. “I have to actually do something meaningful with it to make it a new invention.”

Myriad and others have shot back with the argument most often used to defend the patent system: Patents exist to incentivize research and innovation. Without the possibility of patenting a product, the investment necessary to fund research would drastically decrease. However, patents can also create serious roadblocks to innovation—especially in the world of scientific research, which relies heavily on full disclosure and the open exchange of ideas.

“Granting patents on genetic information not only obstructs progress in both basic research and medicine, it is an intellectually ludicrous practice,” says Michael Eisen, Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology at UC Berkeley. “It’s hard to overstate how much this interferes with research…it has led to the creation of a universe of material transfer agreements and other legal obstacles to the free flow of ideas, information, and resources.”

The Myriad case, if taken up by the Supreme Court, could completely shift how we view ownership of our own human biology, and more tangibly, how affordable and available personalized medicine will be for patients. In this case, Myriad’s stand-alone $3,000 test for the BRCA mutations might no longer be the only option for someone interested in learning their chances of developing breast cancer.

“There are 25,000 genes in every human cell; if we allow patents on that, there’s going to be a toll booth set up on every inch of our genetic code,” says Ravicher.