Icebergs around Cape York, Greenland. Credit: Mila Zinkova via Wikimedia Commons.The National Snow and Ice Data Center’s (NSIDC) latest polar ice report is in and the big news is that this winter might be a lot different from last, even though we’re still in the middle of a La Niña.

Icebergs around Cape York, Greenland. Credit: Mila Zinkova via Wikimedia Commons.The National Snow and Ice Data Center’s (NSIDC) latest polar ice report is in and the big news is that this winter might be a lot different from last, even though we’re still in the middle of a La Niña.

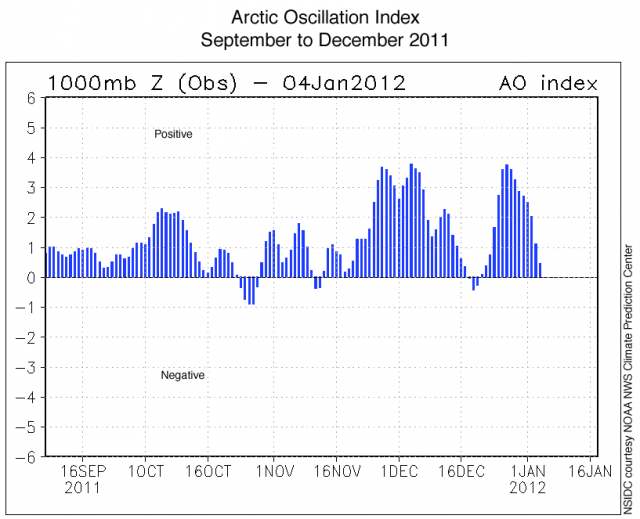

The reason is the appearance of a mostly positive phase of the Arctic Oscillation (AO), which tends to produce less snow and warmer-than-average temperatures over the wintertime North America and Eastern Europe.

Daily Arctic Oscillation Index values from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center, Sept 2011 to Jan 2012, showing relative pressure anomalies between polar and mid-latitude regions. : Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA NWS Climate Prediction Center.

Daily Arctic Oscillation Index values from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center, Sept 2011 to Jan 2012, showing relative pressure anomalies between polar and mid-latitude regions. : Credit: NSIDC courtesy NOAA NWS Climate Prediction Center.

Last winter saw the opposite: tons of snow and really cold temps over much of North America and Europe and warmer-than-normal conditions over much of the Arctic. That’s because a negative Arctic Oscillation took hold. I wrote about that here.

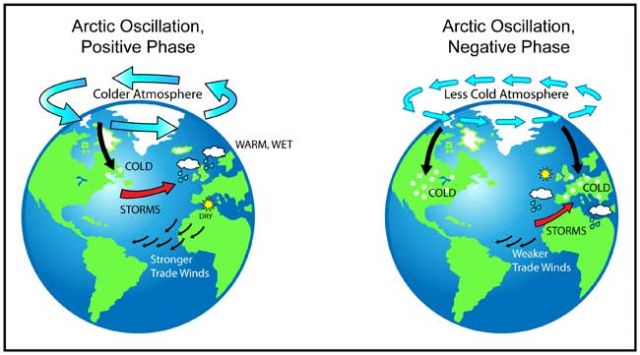

Arctic Oscillation: positive phase (left) has higher air pressure in mid-latitudes than in Arctic, leading to milder winter for US; negative phase (right) has higher air pressure over Arctic, pushing frigid, wet air into US.: Credit: NASA.Technically, the Arctic Oscillation is a measure of atmospheric pressure variations at sea level north of 20N latitude. Where an Arctic high develops affects weather thousands of miles away.

Arctic Oscillation: positive phase (left) has higher air pressure in mid-latitudes than in Arctic, leading to milder winter for US; negative phase (right) has higher air pressure over Arctic, pushing frigid, wet air into US.: Credit: NASA.Technically, the Arctic Oscillation is a measure of atmospheric pressure variations at sea level north of 20N latitude. Where an Arctic high develops affects weather thousands of miles away.

Last year the so-called “Arctic fence” that keeps cold air penned up in the north broke down, allowing frigid air to spill south. So far that’s not happening this winter. Though the AO is a fickle—not seasonal—phenomenon and can switch up at any time.

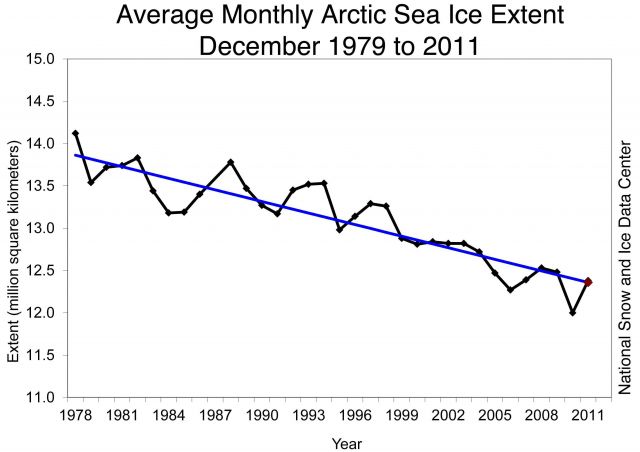

Monthly December ice extent for 1979 to 2011 shows a decline of 3.5% per decade. Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Monthly December ice extent for 1979 to 2011 shows a decline of 3.5% per decade. Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The NSIDC report points out that during a positive Arctic Oscillation, like now, thick sea ice tends to migrate through Fram Strait between Greenland and Iceland, leaving much of the Arctic with thinner ice that melts out more easily the following summer.

In the graph above you can see the precipitous decline of December Arctic sea ice—averaging -3.5 percent per decade since 1979—a trend that’s stronger than the AO alone.

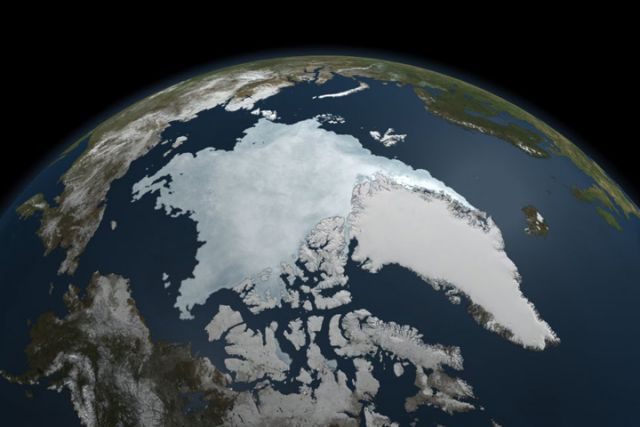

Arctic sea ice extent on 9 September 2011, the 2nd lowest extent on record.: Credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

Arctic sea ice extent on 9 September 2011, the 2nd lowest extent on record.: Credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

After last year’s warm Arctic winter, the 2011 summer sea ice extent was the second lowest on record. (FYI, August sea ice is declining by 9.3 percent per decade… HT @Sustainable2050 for that stat.)

Which means we started this winter with a major deficit. And even though sea ice grew slightly faster than normal in December 2011, and even though temperatures in much of the Arctic were lower than normal in December, overall sea ice cover was still below average. In fact, the third lowest on record.

The five lowest December sea ice extents have all occurred in the past six years.  Polar bear swimming. Credit: Mila Zinkova via Wikimedia Commons.

Polar bear swimming. Credit: Mila Zinkova via Wikimedia Commons.

The positive feedback loop between less ice, open sea water, and escalating temperatures can be seen in the Atlantic side of the Arctic, in the Kara and Barents seas. Higher-than-average December temperatures there were at least partially a result of of dwindling sea ice, allowing more heat to escape from open sea water and further warm the atmosphere.

The eastern coast of Hudson Bay didn’t freeze entirely until late December. Normally, it’s completely frozen over by the beginning of December. That’s a bad start to the winter for Hudson Bay polar bears.