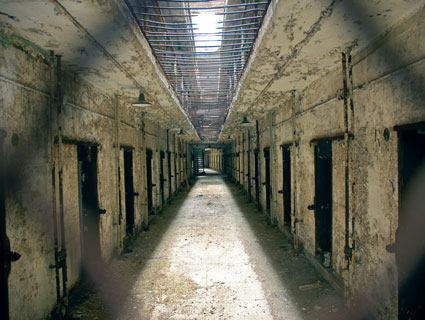

<a target="_blank" href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/paulk/3080299313/">Paul Keller/Flickr</a>

Following a long tradition of tactical White House holiday news dumps, President Barack Obama quietly signed the National Defense Authorization Act Saturday. Obama released a signing statement that pledged to avoid, disregard, and in some cases grudgingly accept new restrictions imposed by Congress.

Detention of American citizens. This was the most controversial section, of the bill, and the most misreported. A Senate compromise amendment to the bill leaves open the question of whether the 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force against the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks authorizes the president to detain American citizens suspected of terrorism who are captured on American soil. This matter may never be settled, as the risk of getting smacked down by the courts may dissuade presidents with even more expansive views of executive power than Obama from ever trying it.

In his statement, Obama says he wants “to clarify that my Administration will not authorize the indefinite military detention without trial of American citizens.” He continues: “Indeed, I believe that doing so would break with our most important traditions and values as a Nation.” Note what the president does not say: that indefinitely detaining an American suspected of terrorism would be unconstitutional or illegal. Obama’s signing statement seems to suggest he already believe he has the authority to indefinitely detain Americans—he just never intends to use it. (In the context of hot battlefields the courts have confirmed he does indeed have that power.) Left unsaid, perhaps deliberately, is the distinction that has dominated the debate over the defense bill: the difference between detaining an American captured domestically or abroad. This is why ACLU Director Anthony Romero released a statement shortly after Obama’s arguing the authority in the defense bill could “be used by this and future presidents to militarily detain people captured far from any battlefield.”

Mandatory Military Detention For non-citizen terrorism suspects. Originally, this provision would have mandated military custody for non-citizen terrorism suspects, like convicted underwear bomber Umar Abdulmutallab, who are captured on American soil. In the final version of the bill, enough loopholes were created in the “mandatory” provisions as to allow the administration to essentially avoid the restrictions. Based on his signing statement, that’s exactly what Obama intends to do. “Moving forward, my Administration will interpret and implement the provisions described below in a manner that best preserves the flexibility on which our safety depends and upholds the values on which this country was founded.” However, signing this bill still creates an assumed role for the military in domestic law enforcement, and will allow critics to accuse the president of ignoring the will of Congress next time a non-citizen terror suspect is captured on American soil.

Detention Review in Afghanistan. The Obama administration drew some cautious praise from human rights groups a few years ago for revamping the process by which the military determines whether detainees in Afghanistan are in fact enemy fighters. But as Marcy Wheeler noted Saturday, the defense bill would have gone further, allowing military judges to preside over status determinations and detainees to be represented by military counsel should they so choose. One legal observer suggested to me that this level of legal review in a battlefield context could be historically unprecedented in terms of the degree of due process it granted to detainees, particularly since those in Afghanistan do not have the right to habeas review in American courts. Unfortunately, the signing statement suggests that Obama may intend to disregard this provision entirely. The statement reads that “my Administration will interpret section 1024 as granting the Secretary of Defense broad discretion to determine what detainee status determinations in Afghanistan are subject to the requirements of this section.” Human rights experts have argued that Obama’s original reforms to the review process didn’t change much.

Guantanamo Transfer Restrictions. No one is getting out of Gitmo any time soon unless it’s in a body bag, not even the dozens of detainees who have already been cleared for transfer. The defense bill maintains restrictions on transfers out of the Guantanamo Bay detention center that Pentagon General Counsel Jeh Johnson has said are “onerous and near impossible to satisfy.” No detainees have been transferred out of Gitmo since the restrictions were first put in place during 2010’s lame duck session of Congress. Obama’s signing statement says that where the restrictions “operate in a manner that violates constitutional separation of powers principles, my Administration will interpret them to avoid the constitutional conflict.” That implies Obama could disregard the transfer restrictions, but given that they’ve been in place for a year without that happening, I wouldn’t hold my breath.

Given that the White House withdrew its veto threat following changes to the final version of the bill, this outcome was expected. However, this is really just the latest skirmish in a much larger fight about where the battlefield lines are drawn, and to what degree legal issues raised by the US fight against Al Qaeda and like-minded groups allow the government to disregard longstanding restraints on government power. For the first time in a long time, however, people may be starting to recognize that these debates affect Americans themselves, not just anonymous foreigners easily written off as terrorists with no rights anyone is bound to respect.