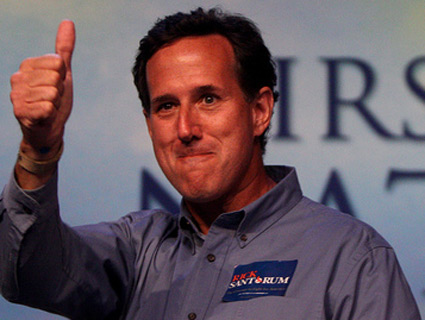

Photo illustration by Dave Gilson

As a kid growing up in western Pennsylvania, Rick Santorum spent his Saturday mornings glued to the television set, watching pro wrestling. Santorum, a comic book fan, saw the contests as bouts of good versus evil, with guys like Bruno “Living Legend” Sammartino (known for such moves as the pendulum backbreaker and the airplane spin) and George “The Animal” Steele playing the perfect heroes and villains.

Santorum played up his love of wrestling in a 2006 campaign ad, which compared Washington to a chaotic wrestling ring and depicted him clotheslining a bare-chested heel:

“Professional wrestling matches, as bizarre as they were and are, at least began as morality plays,” Santorum wrote in his 2005 book, It Takes a Family. “Good guys, literally wearing white, fought bad guys, literally wearing black.” And as in any good morality play, Santorum argued, there had been a Fall: “Today, professional wrestling is more about titillation than ever. The violence has been sexualized.”

But what Santorum doesn’t bother to acknowledge, however, is how he helped make that happen. Though his book briefly notes his stint as the Pennsylvania counsel for the World Wrestling Federation in the late 1980s, it doesn’t mention that he played a critical role in the nationwide deregulation push that turned the spectacle of beefy men in skimpy outfits into a billion-dollar industry—and opened the door for more violence and steroid use.

“Once they deregulated it, then it was kind of like allowing the animals to be in charge of the zoo,” says Jimmy Binns, the former head of the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission, who resigned his post in 1987 during the deregulation push.

Santorum’s wrestling work was the centerpiece of a brief but fruitful lobbying career that began shortly after he graduated from Penn State’s Dickinson School of Law in 1986. Santorum landed a job as an associate with the Pittsburgh firm Kirkpatrick and Lockhart and built up a small client list, including chemical giant Koppers, a local public broadcasting station, and Titan Sports, the parent company of World Wrestling Federation (renamed World Wrestling Entertainment in 2002 and currently known as simply WWE).

At the time, Vince McMahon, the WWF’s slick-haired impresario, was in the middle of a power grab. “Wrestling used to be like the mafia; there were territories,” explains Irvin Muchnick, author of Wrestling Babylon. “There was a national promotional war because of cable, and Vince McMahon won the war. But part of the whole thing was his openly acknowledging that wrestling was fake, which anyone of any intelligence already knew. But he broke the old carnival code and acknowledged it and sort of got a campy rub out of all of that.”

By freely admitting that wrestling wasn’t a legitimate athletic contest, McMahon was able to make the case that it shouldn’t be held to the same regulatory standards as sports. Before the 1980s, most wrestling was under the jurisdiction of state athletic commissions, which were responsible for levying taxes, providing referees, and ensuring basic medical precautions.

Beginning in 1987, Santorum’s mission, as dictated by the WWF, was simple: Get the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission out of the ring. There was no need for state officials to act as referees, because wrestling was a spectacle, not a sport. Nor did it need the state to supply timekeepers, announcers, and doctors—the promoters could take care of that. The new legislation, backed by Santorum and the WWF, would also reduce state taxes on wrestling events, from 5 percent to 2 percent.

That year, Linda McMahon, Vince’s wife and Santorum’s client, advised the Pennsylvania legislature to let the commission’s oversight authority expire. “I don’t think I have to tell you how much prestige and money it would cost Titan Sports if Hulk Hogan or Andre the Giant or any number of our wrestlers were seriously injured and unable to perform,” she testified.

To win lawmakers over, Santorum pulled out all the stops. A 1987 Philadelphia Inquirer story noted that, in the run-up to the vote on the legislation the WWF (with Santorum’s assistance) helped write, the company “treated more than 20 people to complimentary tickets, hot hors d’oeuvres, beer and soda” at a wrestling match. Staffers from the Governor’s Office, including some who had oversight of the State Athletic Commission, “had their photographs taken with Hulk Hogan.”

At the time Santorum dismissed suggestions that his deregulation bill would open up the industry to abuse. If anything, he told the Inquirer, it would give his client an added incentive to keep wrestlers healthy. “These people are their income,” he said, parroting Linda McMahon’s earlier statement. “If Hulk Hogan gets hurt, that’s a pretty big loss to the WWF.” Santorum did not deny that the move was a power grab by the WWF. He told Pittsburgh Press that by upping the per-performance fee to $10,000, his bill would “keep out small-time promoters who don’t run very good shows.”

Santorum, who called the state’s regulatory structure “pernicious” in a later interview, had some legitimate grievances. “They go there, they sit ringside, they bring their friends over the barricade…and they watch the match,” he said of state athletic officials. “That’s how wrestling is regulated in Pennsylvania.” Nothing could justify paying state employees to referee a staged contest: “They made you pay all this money to the boxing commission. They used to just rape these guys,” he said, referring to the state agency’s treatment of wrestling promoters.

Muchnick calls the old regulatory structure “weird and archaic, and in many ways pointless.” But the WWF’s new system only perpetuated existing problems. “With the elimination of any break on excesses by this industry, it has contributed to the occupational health and safety issues that we see, and in the deaths of dozens, scores, or hundreds of young performers in their 20s, 30s, or 40s, depending on how you define, how you slice and dice the various death lists.”

There were also signs that the WWF wasn’t as committed to protecting its athletes as Santorum let on. The deregulation legislation gave the WWF the authority to appoint physicians to ensure wrestlers had stable blood pressure (among other things) prior to entering the ring. But the company was mostly focused on filling seats, not on maintaining its employees’ health. As Muchnick explains, after the law was passed, Linda McMahon retained George Zahorian, a physician with a reputation for selling anabolic steroids and who, according to court testimony, defended his value to the organization thusly: “The boys need their candies.”

It was only when the McMahons caught wind of a federal investigation that Linda cut the doctor loose. Zahorian was convicted in 1991 on 12 counts of illegally distributing drugs. In 1994, with the blessing of immunity from prosecutors, Hulk Hogan testified under oath that he had received steroids from Zahorian. Two years later, the WWF ended its policy of mandatory drug testing.

Binns, one of the few opponents of the Pennsylvania deregulations measure (which passed overwhelmingly in 1989) viewed wrestling promoters as craven operators fixated on the bottom line. “The wrestling powers that be would pay these kids $50 to get—I think they called it juicing—where they would tape their razor blades into their fingers, so when they got hurled against the turnbuckle, they would slice their forehead open,” he says. “I thought that was subhuman.”

Muchnick described the deregulation push in detail in a 1988 piece he wrote for the Washington Monthly. Although he didn’t talk to Santorum for the article, he said got a call from him shortly after it was published. “It was like asshole central,” he remembers. “He was slapping his knees and laughing and reading lines out loud, which at a minimum showed a certain cynicism about the whole thing. But also, it was just very juvenile. I’m sure he didn’t expect to be running for president at that point.”

The Pennsylvania deregulation did eventually become a campaign issue in 2010, when Linda McMahon was the Republican nominee for Senate in Connecticut. Pressed on charges of obstruction of justice stemming from the Zahorian case, McMahon noted that her opponent, Democrat Richard Blumenthal, had voted to deregulate wrestling as a state representative in the 1980s. Yet none of Santorum’s current opponents have weighed in on the former senator’s WWF lobbying.

Wrestling, Santorum writes in It Takes a Family, “is a non-elite artifact of our culture that has survived by trying to keep up with the envelope-pushers in Hollywood and New York.” It was also a cautionary tale, albeit one whose causes he was loath to delve into. “It has been sucked into telling some of the same lies,” he wrote. “Bad culture lies, good culture doesn’t.”