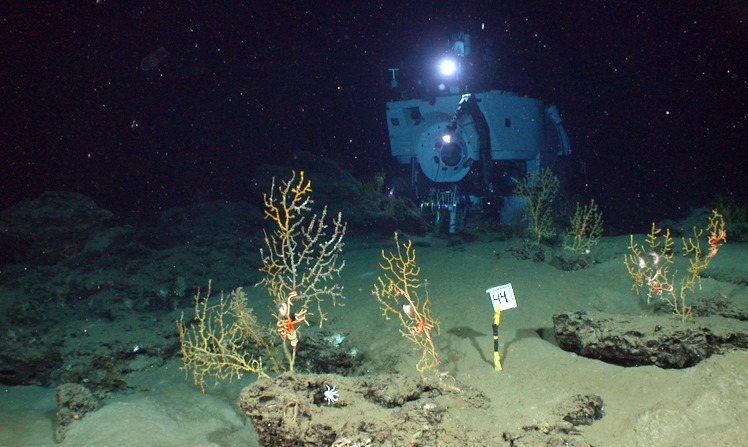

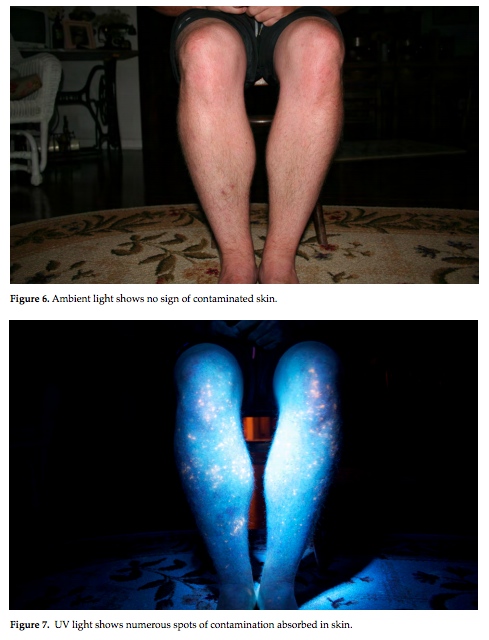

Corexit® dispersed oil residue accelerates the absorption of toxins into the skin. The results aren't visible under normal light (top), but the contamination into the skin appear as fluorescent spots under UV light (bottom).Credit: James H “Rip” Kirby III, Surfrider Foundation

The Surfrider Foundation has released its preliminary “State of the Beach” study for the Gulf of Mexico from BP’s ongoing Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Sadly, things aren’t getting cleaner faster, according to their results. The Corexit that BP used to “disperse” the oil now appears to be making it tougher for microbes to digest the oil. I wrote about this problem in depth in “The BP Cover-Up.”

The persistence of Corexit mixed with crude oil has now weathered to tar, yet is traceable to BP’s Deepwater Horizon brew through its chemical fingerprint. The mix creates a fluorescent signature visible under UV light. From the report:

The program uses newly developed UV light equipment to detect tar product and reveal where it is buried in many beach areas and also where it still remains on the surface in the shoreline plunge step area. The tar product samples are then analyzed…to determine which toxins may be present and at what concentrations. By returning to locations several times over the past year and analyzing samples, we’ve been able to determine that PAH concentrations in most locations are not degrading as hoped for and expected.

Worse, the toxins in this unholy mix of Corexit and crude actually penetrate wet skin faster than dry skin (photos above)—the author describes it as the equivalent of a built-in accelerant—though you’d never know it unless you happened to look under fluorescent light in the 370nm spectrum.? The stuff can’t be wiped off. It’s absorbed into the skin.

And it isn’t going away. Other findings from monitoring sites between Waveland, Mississippi, and Cape San Blas, Florida over the past two years:

- The use of Corexit is inhibiting the microbial degradation of hydrocarbons in the crude oil and has enabled concentrations of the organic pollutants known as PAH to stay above levels considered carcinogenic by the NIH and OSHA.

- 26 of 32 sampling sites in Florida and Alabama had PAH concentrations exceeding safe limits.

- Only three locations were found free of PAH contamination.

- Carcinogenic PAH compounds from the toxic tar are concentrating in surface layers of the beach and from there leaching into lower layers of beach sediment. This could potentially lead to contamination of groundwater sources.

The full Surfrider Foundation report by James H. “Rip” Kirby III, of the University of South Florida is open-access online here.