Tim McDonnell

Generation Xers grew up with MTV, Nirvana, and the dot-com bubble. Today, Americans born roughly between 1961 and 1981 are better educated and work longer hours than their parents, sit on their children’s school boards, and take active roles in their communities. But when it comes to climate change, Gen Xers voice a resounding “meh.” Tim McDonnell

Tim McDonnell

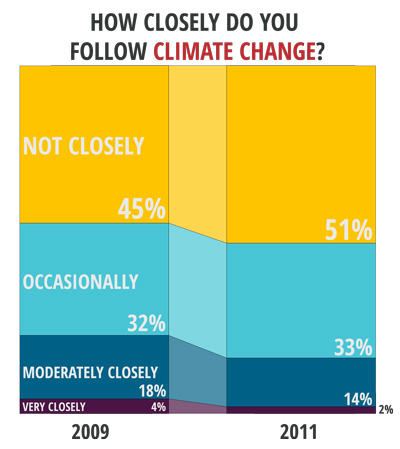

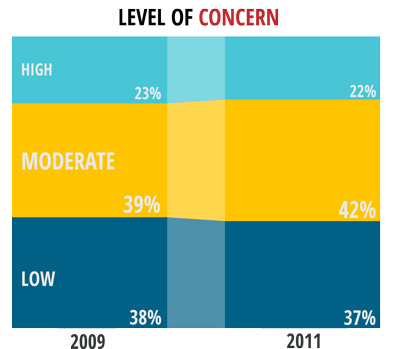

That’s the result of a University of Michigan study that polled some 3,000 Gen Xers and found that in the last several years their overall interest in climate change has waned.

Sociologist Jon Miller, the study’s author, sees this as a sign of victory for the climate disinformation campaign. “I was optimistic because this group of people is more scientifically literate; they’ve grown up in an era of of science and quantitative discussion, unlike their grandparents,” Miller says. But the complexity of climate science, the long time scale it takes to play out, and seeds of doubt sown on the nightly news have caused many Gen Xers to simply tune it out.

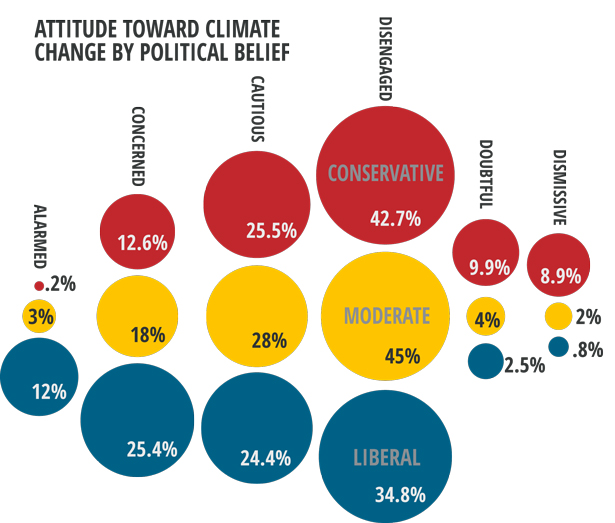

The data shows a broad “migration to the middle,” says Miller, with passionate voices on both ends of the spectrum quieting down in favor of passive disengagement. Tim McDonnell

Tim McDonnell

The trend cuts through the political spectrum, as the chart at the top of this post shows: Conservative, moderate, and liberal Gen Xers alike felt more “disengaged” about climate change than any other attitude (details on those categories here). Not surprisingly, conservatives were overwhelmingly less concerned about climate change than liberals, with moderates split more or less evenly.

Climate change is one of the most politicized scientific issues in recent history. Miller says that when faced with loud debate over a subject they don’t fully understand and whose full impacts seem to be on the horizon, most people will just stick with their political party lines. “Democracy works best on short-term issues, so [climate change] is a real challenge,” he says.

But stepping outside the Gen X bubble, a string of recent climate-related surveys suggest a society more ready and willing to grapple with global warming could be in the offing.

In December, a Pew poll found a “modest” rise in the number of people who see solid evidence of global warming. A Gallup survey in April found that 70 percent of Americans support higher greenhouse gas emissions standards for business and industry. And this month, a Washington Post-Stanford University study found that while climate change is no longer Americans’ top environmental concern, three-quarters believe the planet is warming and that it will continue to do so if nothing is done.

So what gives, Gen Xers? Miller said one of the most reliable ways to grab their attention was with issues that affect the daily lives of their kids—the flu, for example. Maybe climate science communicators need to do a better job convincing young parents that the state of the world their kids will grow up in—one with higher seas, worse storms, punishing summers—is something they should think about today.

“We have to say, ‘Look, it’s not going to be easy’,” Miller says. “But I think we should not give up on it.”