South Sudan came into being a year ago but remains fragile today: It is rife with violent conflict and corruption, and sorely lacks infrastructure.

In 2005, a peace treaty between Sudan’s mostly Muslim North and mostly Christian South put an end to Africa’s longest civil war and set in motion a process for the South to become independent. After almost 99 percent of the population voted for separation in January 2011, the leaders of the main Southern rebel group, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, became the de facto leaders of the new nation. Today, the country is among the worst in health and education rankings globally. And President Salva Kiir recently admitted that the country’s leadership stole $4 billion in funds intended for clinics, roads, and schools.

Ongoing violence makes development tough. Clashes persist between rival tribes in South Sudan—often due to competition for scarce resources—and conflicts rage with the North over oil resources and border disputes. In May, the United Nations Security Council approved a resolution threatening both sides with sanctions if the fighting doesn’t cease, and the two states are now discussing a “security road map.” But many worry tensions will escalate again and destabilize the region.

Cédric Gerbehaye, a Belgian documentary photographer, traveled to Sudan on a Magnum Foundation grant in July and August 2010, and returned during the referendum to document a country in transition. “The people were waiting for that historical moment, for that ‘final walk to freedom,'” he said. After subsequent trips, he observed, “It was weird to see such hope within the population and then see that things haven’t really changed.”

This project was funded in part by the Pulitzer Center.

Bir-Diak cattle camp of the Pakam Clan of the Dinka Tribe, Rumbek North Country, Lakes State. During the civil war the cattle keepers were forced to carry weapons and ammunition for the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Since the peace agreement of 2005, it has been easy to obtain weapons left over from the war.

Bir-Diak cattle camp of the Pakam clan of the Dinka tribe, Lakes State. The social structures of the pastoralist societies are based on the possession and successful retention of cattle.

Bir-Diak cattle camp of the Pakam Clan of the Dinka Tribe, Rumbek North Country, Lakes State. Cattle keepers refused to surrender their weapons during the last disarmament because they have to defend themselves during cattle raids that cost many lives each year.

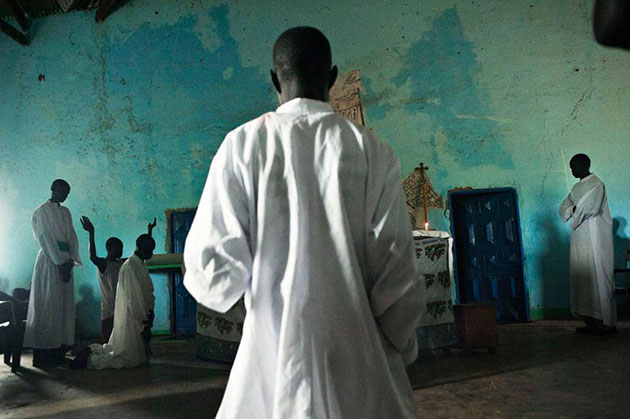

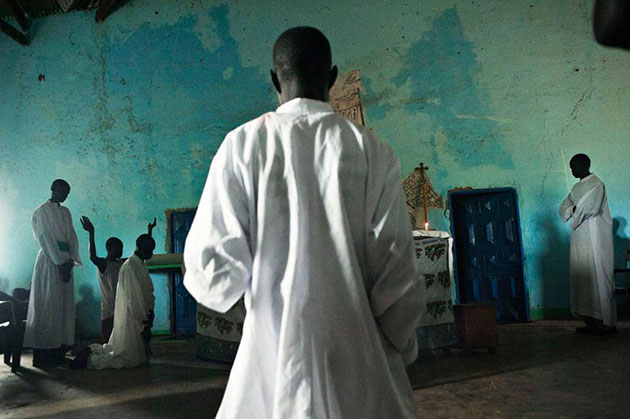

Sunday mass at the church of Gogrial in the Warab State. Southern Sudan is mainly Christian-animist.

A mother with her child in the hospital of Pibor in the Jonglei State. Maternal mortality in South Sudan is one of the highest in the world.

Inside Juba’s prison. The rehabilitation of the prison is supported by the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) and part of the capacity building efforts in South Sudan.

A young boy on the banks of the Gilo River, Jonglei State. His leg was amputated due to lack of care after being bitten by a snake. Access to health care is a major challenge for South Sudan.

A woman waiting for consultation at Aweil Hospital, Northern Bahr-El-Ghazal State. South Sudan has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world, with one in seven women likely to die due to pregnancy related causes.

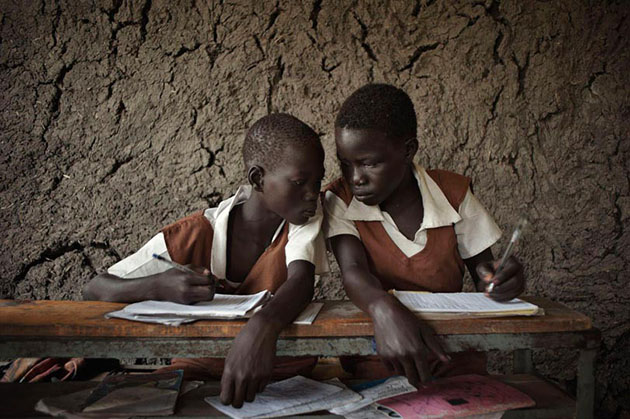

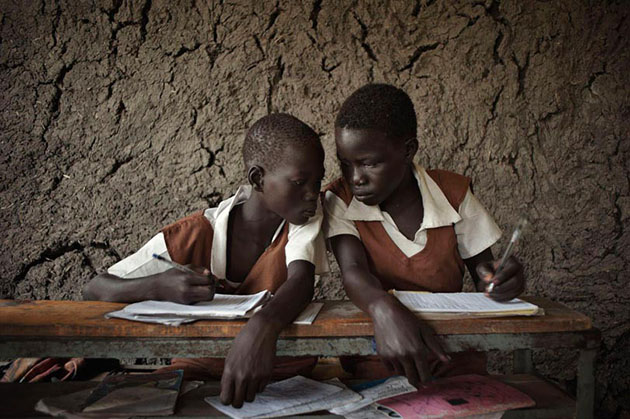

Students in a village school in Owachi, located next to the Nile, in the Upper Nile State. Women’s literacy in South Sudan stands at 16 percent, and a 15-year-old girl has a greater chance of dying in childbirth than completing her education.

Before Sunday prayer at the Catholic Church of Mary in Abyei.

Abdellah Kuma looking after his daughter Orchelim who just had her right arm amputated. Her house of Al Buram in the Nuba Mountains in Southern Khordofan, Sudan, was bombarded by the SAF (Sudanese Armed Forces) while she was preparing breakfast for her family.

From his desk, the shopkeeper of Geng Petroleum, a gas station, is looking at the customers. Opened the day before, the gas station is the first one owned by a Bentiu inhabitant, Unity State.

The first day of the referendum on January 9th, 2011. Bentiu inhabitants in Unity State stand in line at a polling station before voting.

At the end of the day Martin Lou Lawrence, a mechanic who works on water pumps near the Nile River, looks at the last trucks filling up. Juba city, South Sudan’s capital, has no running water system. Near Knoyo Konyo Market, one filling station with 24 pumps fills up 200 trucks a day with non-treated Nile River water to supply the city.

After a long journey by bus, people who have come back to vote for the referendum have their personal effects returned from the trucks that brought them from Khartoum to Bentiu, the capital of Unity State.

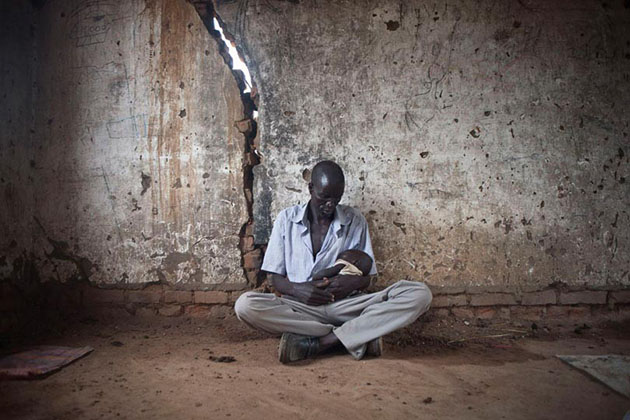

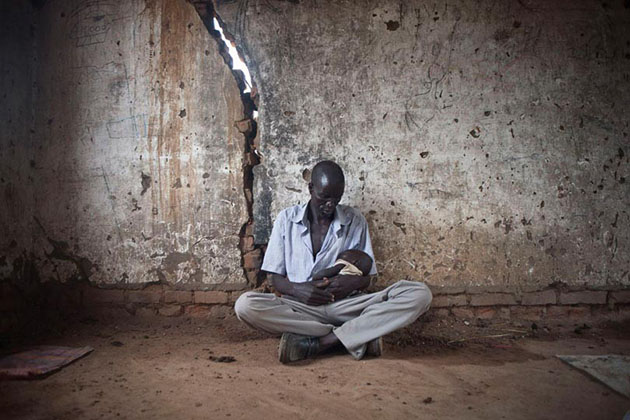

Sabrino Mayol and his son Blue, as well as the rest of the family, found shelter in a building next to the church of Mayan Abun in the state of Warrap. They ran away from the fights between the SAF (Sudanese Armed Forces) and the SPLA (Sudan People’s Liberation Army) in Abyei.

Raby, 8-years-old, at the transit center that welcomes returnees from the north and the IDPs following the fighting between the SAF and the SPLA in Abyei. Wau , Northern Bar-el-Ghazal State.

This project was developed with support from the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund, in partnership with Mother Jones. The Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund supports experienced photographers with a commitment to documenting social issues, working long-term, and engaging with an issue over time.