The pale grass blue butterfly, Zizeeria maha.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/tuis_imaging/5673815947/in/photostream/">Tuis</a>/Flickr

Last March, the 9.0 magnitude T?hoku earthquake triggered a tsunami that sent over 45-foot waves of water crashing down on the reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant, causing the largest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986. While health officials scrambled to quickly stabilize the situation, it was unclear how much radiation had made it out of the plant—and how it could affect people, plants, and animals who came into contact with it.

Preliminary studies concluded that most of the 140,000 people in the surrounding areas of Fukushima had probably been exposed to relatively low doses of radiation that probably wouldn’t lead to any adverse health effects. But a new study published last week in Nature has shown that the radiation is causing a particularly sensitive population—the pale grass blue butterfly—to develop a slew of uncommon and potentially lethal physical abnormalities.

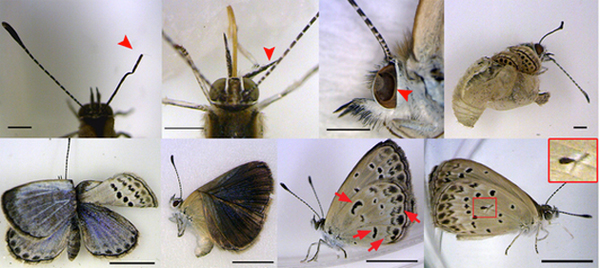

Researchers collected butterflies immediately following the nuclear meltdown and six months later, both from the surrounding areas of Fukushima and from various other localities in Japan where the butterfly is common. As compared with the butterflies collected from elsewhere in the country, Fukushima butterflies showed some abnormally-developed legs, dented eyes, deformed wing shapes, and changes to the color and spot patterns of their wings, with an overall abnormality rate of around 12 percent.

Mutations included malformed antennae, dented eyes, bent wings, and abnormal color patterns. Photo courtesy of Joji M. Otaki

Mutations included malformed antennae, dented eyes, bent wings, and abnormal color patterns. Photo courtesy of Joji M. Otaki

While these levels of mutations were still relatively mild, perhaps more alarming were the same data on butterflies collected six months later, in September of last year. The overall rate of similar mutations among these butterflies was around 28 percent, while this number skyrocketed to around 52 percent in the second generation produced from the collected butterflies.

To make sure that the mutations were really caused by the radiation from Dai-ichi power plant, the researchers exposed normal butterflies to similar low levels of radiation that were released following the tsunami and saw comparable results. Since the Fukushima butterflies were also being exposed internally by eating leaves affected by radiation, they also fed normal butterfly larvae radiated plants and saw similar mutations emerge. Based off this, the researchers concluded that the mutations being seen in the Fukushima butterflies are due both to external and internal contact with radiation.

The study renews worries that humans, too, might be affected by the released radiation in the Fukushima area, but the researchers insist that this is not an easy line to draw. “Humans are totally different from butterflies and they should be far more resistant,” the head scientist on the study, Joji M. Otaki, told The Japan Times. So while the butterfly study is the first to definitively link Fukushima radiation to physical mutations in any organism, they are certainly not the only ones to be exposed; it remains to be seen if similar effects can be seen across species. Let’s hope not.