A Lebanese cedar.<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=2262372">Sybille Yates</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

King Solomon used them in the construction of the temple that would bear his name, the Phoenicians used them to build their merchant ships, and the ancient Egyptians used their resin in the mummification process. But now Lebanon’s cedar trees (Cedrus libani), described in the Scriptures as “the glory of Lebanon” and by the 19th-century French Romantic poet Alphonse de Lamartine as “the most famous natural monuments in the world”, face a new threat in the form of climate change.

Emblazoned on the national flag, currency, and the country’s national airline, the cedar is the one great unifying emblem of this small Mediterranean nation. Centuries of deforestation have already seen the tree’s 500,000 hectares decimated to its current 2,000 hectares, and it has been added to the IUCN’s red list of threatened species, albeit at the lowest level of threat.

The cedars, some up to 3,000 years old and almost all of which are now protected, need a minimum amount of snow and rain for natural regeneration. But global warming has meant that Lebanon’s cedars are being subjected to shorter winters and less snow, and the Lebanese government estimates that snow cover could be cut by 40 percent by 2040.

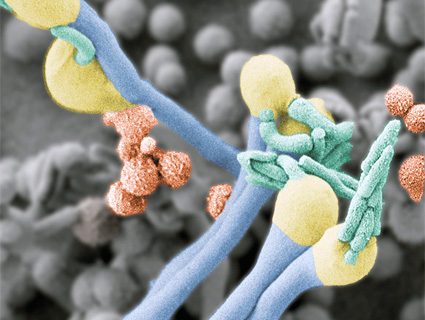

Nabil Nemer, the head of the agricultural sciences department at Lebanon’s Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, said that the lack of snow was not the only problem linked to climate change. “Insects, due to the changing climatic condition, become more active and their development rate is faster, thus causing more outbreaks, which weaken the cedar tree, making them more susceptible to other diseases and/or insects, which will ultimately kill the trees,” he said. “At least one insect has been studied, and the results showed that outbreaks of this insect are due to climate change, a low period of snow, and low humidity in summer. This insect, the Cephalcia tannourinensis, is a serious cedar tree defoliator.”

But, with sectarian difficulties forever dominating the political agenda, the fight to preserve Lebanon’s cedars can be a frustrating one. Nemer, who is also project coordinator of Support to Nature Reserves of Lebanon, said that while the Lebanese government was concerned about the threat to its emblem, not enough was being done to stop deforestation and plant new cedars: “Whether what is being done is enough—it is enough when you see the number of groups involved and it is not enough when you observe what is done, how it is done and by whom.”

Elsa Sattout, whose doctorate entailed a multidisciplinary study of Lebanon’s cedar forests, defended the country’s approach and noted the cedar is protected by law, but said more could be done.

“There are many reforestation projects undertaken by nongovernmental organizations and funded by international agencies, which have and are taking place, but, for me, these could have been more successful,” she said. Since 2009, for example, Starbucks and the Association for Forest Development and Conservation have partnered to plant several thousand cedars in areas of Lebanon afflicted by forest fires.

She also highlighted a mass spraying project against Cephalcia tannourinensis in a joint effort between the American University of Beirut and the ministries of agriculture and environment.

A spokesman from the country’s Lebanese agricultural ministry told the Guardian: “When, for example, the threat of the Cephalcia tannourinensis was discovered in the Tannourine nature reserve we had experts from France to assess the danger and they suggested the insecticide to use, which we dropped using helicopters and were successful in drawing an environmental balance—and keeping the insect at bay. The cedars are our treasure and we need to preserve this treasure for many hundreds and thousands of years to come.”