<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/22620936@N04/5548801701/">Jim Larson</a>/Flickr

With six weeks until Election Day and Barack Obama’s polling advantage holding steady, a new narrative is emerging about the first presidential election of the super-PAC era. It goes something like this: All the hue and cry about outside interests buying the election has been misguided; in fact, about the only thing super-PACs have been good for is blowing their rich backers’ money. “A summer of vast campaign spending and dark warnings about sinister, secret donors is on the verge of being replaced by a fall in which rich men spend a lot of time explaining to their wives why they wasted millions of dollars,” Buzzfeed‘s Ben Smith wrote last week. In July, the New York Times’ Matt Bai made a similar case that the impact of the Citizens United decision that made super-PACs possible had been overstated.

We won’t know the full story until after the election, but it’s too early to completely write off super-PACs. A few reasons why:

1) Super-PACs may have helped keep Romney in the game: The Obama campaign has raised $150 million more than Romney’s. However, the $143 million already spent by outside groups opposing Obama has tilted the money game in Romney’s favor. “We helped leave this race a statistical dead heat,” Steven Law, president of Karl Rove’s American Crossroads super-PAC, told the Wall Street Journal. “Obama has gotten almost nothing for all the money his campaign has invested.” Likewise, Gary Bauer, the former GOP presidential candidate who runs the anti-gay marriage super-PAC Campaign for American Values, told the Journal, “If Romney didn’t have the help from the outside groups that he’s had, this race would be over.”

However, this reliance on super-PACs could also hurt Romney. Campaigns and super-PACs aren’t allowed to coordinate (at least not too obviously), which can make message discipline tough. The Romney campaign “has to guess at what it thinks other people are going to say and where they are going to say it, and then has to deploy its resources where it thinks there will be gaps, and that’s a hard guessing game to play,” Brad Todd, a GOP ad man, told the Los Angeles Times. And as Romney’s fortunes wane, groups like American Crossroads appear ready to shift more resources to down-ballot candidates, and could withdraw their support for him altogether—what Washington Post‘s Ezra Klein calls “Romney’s nightmare scenario.”

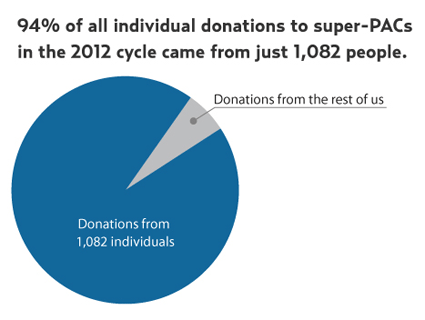

2) Super-PACs have amplified megadonors’ influence: Wealthy donors love to get up close and personal behind closed doors with the politicians they fund, as our reporting on the Koch brothers’ secret confabs and Mitt Romney’s 47 percent gaffe show. Super-PACs have given this elite group a new avenue for catching lawmakers’ attention. As casino magnate Sheldon Adelson told Politico, “I don’t believe one person should influence an election. So, I suppose you’ll ask me, ‘How come I’m doing it?’ Because other single people influence elections.”

As Bai noted, superdonors already had ways to write big checks before Citizens United. Yet unlike 527 groups, super-PACs can advocate for specific candidates, and there’s little chance that candidates are ignoring the donors using super-PACs to sidestep limits on campaign donations. And even after the election, super-PACs will remain on the scene to infuence policy and politicians’ votes. They’re already getting into the lobbying game.

On the other hand, megadonors aren’t exactly expert strategists. No one has made this more clear than Adelson himself, who along with his wife Miriam has poured $36 million into super-PACs—including $10 million to Newt Gingrich as his primary campaign was imploding. Money may guarantee that a donor’s voice is heard, but money can’t always save a loser.

3) Super-PACs are shaking up state races: Even those who argue that the impact of Citizens United has been overstated, like Bai, have pointed to congressional races as an exception. Super-PACs like the antitax Club for Growth Action have poured millions into state races, from Arizona to Wisconsin, typically influencing the outcome. In Texas, a 21-year-old millionaire helped a Rand Paul-backed House candidate win his GOP primary. And super-PACs aren’t limited to spending on federal races: Rich out-of-state donors helped push its total cost of June’s recall election in Wisconsin beyond $60 million.

4) Super-PACs are flooding the airwaves: Analysts predict that more than $3 billion will be spent on political ads in this election cycle (including twice what was spent in 2008 on cable ads). According to a recent Sunlight Foundation study, Citizens United is directly responsible for 78 percent of spending from outside groups this election.

5) Dark money still matters: Even if super-PACs have been overhyped, there’s still no denying that outside money is playing a bigger role than ever before in this election. That’s especially true when you figure in 501(c) “social welfare” nonprofits, which have spent more money on ads than super-PACs. We may not appreciate their influence until the election is over. As the IRS has gotten more aggressive in determining whether 501(c)s have violated their tax-exempt status, the groups have become more adept at skirting new rules to keep toothless regulators at bay. And if that trend continues, reformers predict, outside spending in the future will dwarf 2012’s numbers.