The Science Conference Lounge. Julia Whit

The Science Conference Lounge. Julia Whit

Editor’s note: Julia Whitty is on a three-week-long journey aboard the the US Coast Guard icebreaker Healy, following a team of scientists who are investigating how a changing climate might be affecting the chemistry of ocean and atmosphere in the Arctic.

Every other night someone gives a lecture in the Science Conference Lounge at 7pm. First up was Captain Beverly Havlik, Commanding Officer of USCGC Healy. She gave a riveting seafaring description of the Healy‘s pivotal role in keeping the people of the city of Nome from freezing last winter.

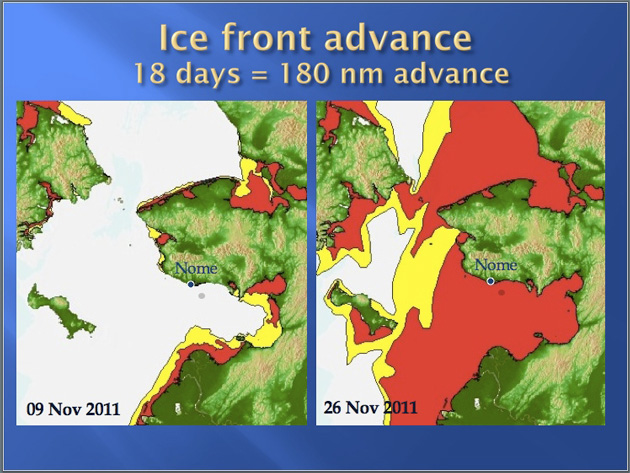

Advance of the sea in in the Bering Sea near Nome from 09-26 November 2011. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

Advance of the sea in in the Bering Sea near Nome from 09-26 November 2011. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

You might remember the story. An early monster of a storm swept through the Bering Sea 08-10 November 2011, which turned around the tug and barge delivering fuel to Nome. In the wake of the storm, sea ice closed in too fast for the vessels to return. In the maps above you can see how the ice front advanced a whopping 180 nautical miles (207 miles) in only 18 days.

The Russian tanker Renda steaming in the wake of USCGC Healy in the Bering Sea. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

The Russian tanker Renda steaming in the wake of USCGC Healy in the Bering Sea. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

Since there are no roads connecting Nome to the outside world, the people there rely on sea and air cargo for virtually all of their goods. As Captain Havlik explained, it would be tough for flights to make up the 1.3 million gallons of fuel a tanker ship normally delivers. The equivalent by air would require 270 flight—which are also vulnerable to weather during the Alaskan winter. But what if the US Coast Guard icebreaker Healy could lead a tanker ship to Nome? Turns out the only tanker available was the T/V Renda, a Russian ship. So bureaucracies were laid aside. And the crew of Healy, who were looking forward to steaming home to Seattle for the December holidays after an extremely long season in the Arctic, were told they were needed in the north again.

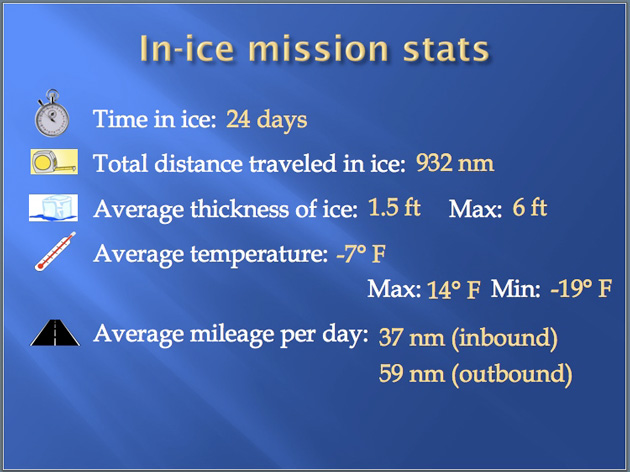

The two ships entered the ice on 06 January (map below), 365 nautical miles (420 miles) from Nome. Healy broke ice and Renda steamed in her wake. When Renda bogged down, Healy performed a variety of icebreaking maneuvers to free her. Though none of it was that easy. Captain Havlik described the many frustrations: translation problems between Russian and American crews; issues of trust (since the icebreaker needed to steam extremely close to Renda to cut her free); extreme cold; the ever-changing pack ice.

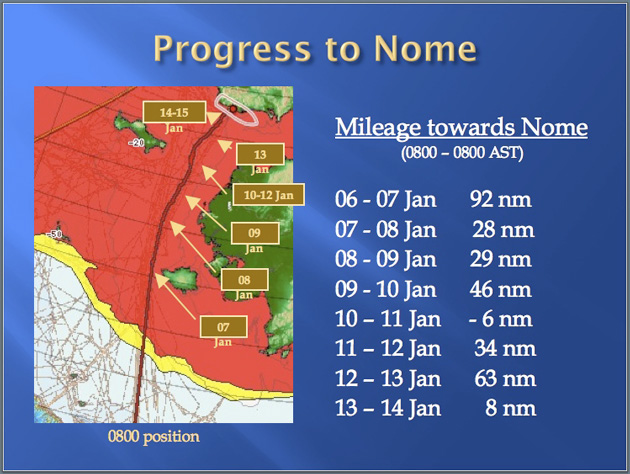

Progress to Nome (1 nautical mile = 1.15 miles) of Healy and Renda, 2012. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

Progress to Nome (1 nautical mile = 1.15 miles) of Healy and Renda, 2012. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

In the map above you can see their progress through the ice. Some days were better than others. There were other considerations too. A transit closer to Saint Lawrence Island (center of map) would likely have provided something of a lee shore from winds and ice. But the island is critical winter habitat for the endangered sea ducks known as spectacled eiders, so that was a no go.

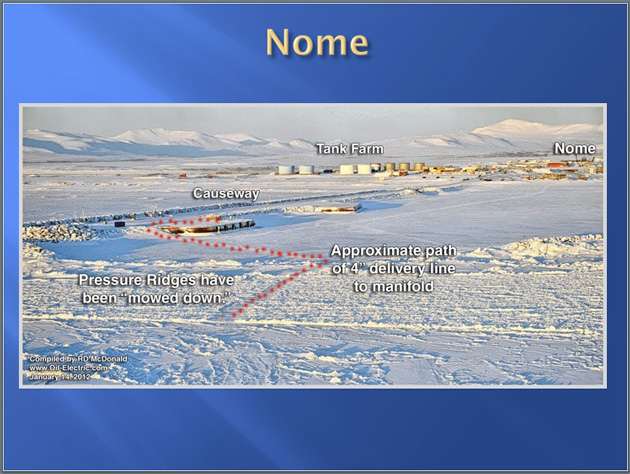

Nome, January 2012. The red dotted line shows where the fuel hose connecting T/V Renda to the town was laid. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard.

Nome, January 2012. The red dotted line shows where the fuel hose connecting T/V Renda to the town was laid. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard.

After eight days plowing through a frozen sea, the two ships arrived at the port of Nome. Because the harbor was too shallow for Healy‘s draft all the fuel had to be offloaded 460 yards from shore. A path was mowed through the pressure ridges in the ice and two hoses were laid out connecting the fuel tanks on Renda with the fuel tanks in Nome. The pumps ran nearly nonstop for the next 60 hours. The citizens of Nome turned out to help. A few Alaskans from other parts of the state flew in to help. The Healy and Renda crews were thanked with batches of cookies and cakes from the people of Nome.

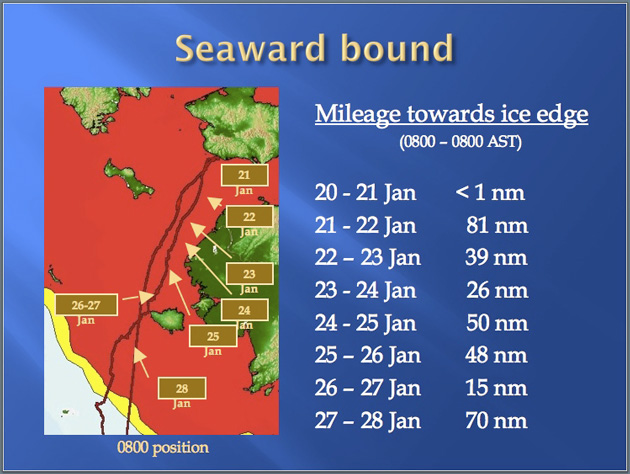

Return progress of Healy and Renda through the ice. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

Return progress of Healy and Renda through the ice. Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

By the time the fuel transfer was complete and the ships started back south the pack ice had grown further and open water was now a daunting 500 nautical miles (575 miles) away. But Healy and Renda had a working system in place. And they were steaming with the wind this time. As you can see from the map above, they made better time.

In-ice mission stats Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

In-ice mission stats Image courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

“The crew of Healy was outstanding,” said Captain Havlik. And the mission was proof that the US needs more icebreakers. USCGC Healy is currently the only operational icebreaker in the the US fleet—Coast Guard or Navy.