Update: On November 6, Matheson narrowly survived yet again, beating Mia Love by fewer than 3,000 votes.

The congressional career of Rep. Jim Matheson (D-Utah) has often seemed like a decadelong exercise in political survival. Utah Republicans have twice tried to redistrict him out of office, and he presently represents the most solidly GOP district in America held by a Democrat. One of a fast dwindling cadre of conservative “Blue Dogs,” Matheson is Utah’s lone congressional Democrat—and in November Republicans may finally succeed in their long crusade to pick him off.

Nationally, conservative Democrats like Matheson are an endangered species. In 2010, more than 50 Blue Dogs served in the House. Today there are 24, and 4 of them are either retiring or running for the Senate. Like many of the remaining 20 House Blue Dogs, Matheson’s fate is very much in doubt.

The six-term incumbent is locked in a tough race against upstart Mia Love, the conservative mayor of Saratoga Springs, Utah, who has overnight become one of the GOP’s rising stars and a tea party sensation. Over the summer, Matheson held a double-digit lead over Love. The latest poll shows the race a virtual dead heat, with 14 percent of voters still undecided.

The national GOP has helped close the gap by pouring money into ads, dispatching party luminaries to fundraise for Love, and opening a call center in Salt Lake City. But Love has also benefited from another factor: gerrymandering.

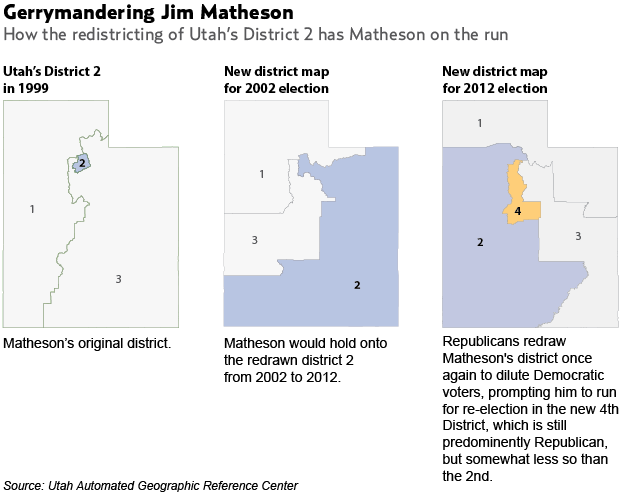

When Matheson was first elected in 2000, his district consisted entirely of Salt Lake County, an area that’s home to the highest percentage of registered Democrats in the state. A year later, the GOP-dominated state Llegislature redrew the boundaries of the 2nd District to dilute the power of Democratic voters, excising chunks of Salt Lake County while adding large rural stretches of the state. Parts of Matheson’s new district were a five-hour drive from his home in Salt Lake. The Cook Report assessed the new 2nd District as one that a generic Republican ought to win by at least 15 points.

Despite this disadvantage, Matheson has managed to hang on to his seat, in part due to his conservative credentials. He was one of 34 House Democrats to vote against Obamacare, and his pro-business voting record is so solid that he is one of just five House Democrats this year to win an endorsement from the US Chamber of Commerce.

Despite this disadvantage, Matheson has managed to hang on to his seat, in part due to his conservative credentials. He was one of 34 House Democrats to vote against Obamacare, and his pro-business voting record is so solid that he is one of just five House Democrats this year to win an endorsement from the US Chamber of Commerce.

Matheson’s name recognition certainly has contributed to his staying power. He hails from Utah’s only Democratic political dynasty. Matheson’s father, Scott, was a popular three-term Democratic governor (the last Democrat to hold that office); his brother is a federal judge.

Unable to beat Matheson at the ballot box, Utah’s Legislature took another crack at rejiggering his district in 2011, this time changing the boundaries to cover even less of Salt Lake County and to exclude Moab, a liberal outpost in far southern Utah, where 50 percent of the voters are Democrats.

When new census data was released in 201O, Utah gained an additional congressional district, so Matheson had the option of choosing to run again in the newly redrawn 2nd District or jumping to the new 4th District. He picked the 4th, which included more of Salt Lake, but which is still overwhelmingly Republican.

This election cycle, the GOP has pulled out the stops to oust Matheson. Everyone from Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) to Condoleezza Rice to Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) has parachuted in to Utah to stump for Matheson’s opponent. Love, meanwhile, has become a surrogate for Mitt Romney, campaigning on his behalf in the critical swing states of Nevada and Ohio and serving on his Black Leadership Council. Mitt Romney’s son, Josh, who lives in Utah, is an adviser to Love’s campaign. And Love may be hoping that her close affiliation with Romney—in a state where the candidate is expected to generate massive voter turnout—will enhance her own prospects at the polls.

To further boost Love’s national profile, the GOP granted Love a coveted speaking slot at the Republican National Convention, which translated into a major fundraising boon for the candidate. Matheson started the race with a large war chest and the fundraising advantages of an incumbent. But following the convention, Love raised twice as much as Matheson did. So far, the candidates have collectively spent nearly $6 million, raising the possibility that the race will break the record ($6.5 million) for Utah’s most expensive political race.

Love’s jump from mayor of Saratoga Springs (population 18,000) into the national political spotlight has not been seamless. In June, she stood up Mitt Romney at the NAACP’s national convention in Houston, where she was scheduled to introduce the presidential candidate, sparking grumbling in GOP circles that Love’s campaign was in disarray. And she gave a bizarre interview to Buzzfeed in August, where she demanded fundraising help from the decidedly nonpartisan site:

“Here’s what I need you to do for me,” she said toward the end of a brief conversation at the Utah Republican Party headquarters. “This is very important. I am running a race against Democrat Jim Matheson, and it’s all hands on deck…I need you to put a ticker on your website to say ‘Donate to Mia Love.'”

When the request was met with mild befuddlement, Love kept pushing: “Seriously! The time has come for us to no longer just stand on the sidelines and watch and see what happens. If you understand and can see the sincerity of what I’m saying, I need people to take a stand…I need you to put a ticker, and we need to raise a million dollars.”

Love, who’s Haitian American, has also stumbled by making her immigrant parents a centerpiece of her campaign, while also supporting draconian immigration policies backed by many in her party. In September, Mother Jones raised the question of whether Love was what some in her party refer to with the derogatory term “anchor baby”—that is, a child born on US soil specifically to help her parents gain legal residency. Love had described herself as “our family’s ticket to America” in a 2011 interview with the Deseret News.

Love didn’t handle the scrutiny well. After Mother Jones‘ story appeared, she claimed amnesia about her comments, then blamed the Matheson campaign for “planting” the story. Eventually, her campaign allowed the Salt Lake Tribune to interview her father, who admitted that he’d worked illegally in the US before gaining residency.

Matheson, by contrast, is a seasoned pol. While politics is in his blood, he is also a former businessman, with a Harvard degree in government and MBA from UCLA. After college, he spent a few years working as a lobbyist for an environmental group in DC now called Friends of the Earth. He can work a room, but he also is fluent in public policy in a way Love is not. Still, his conservative streak hasn’t endeared him to many Utah Democrats who are unhappy with his vote against Obamacare in 2010, among other positions.

While in Saratoga Springs in August, the lone Democrat I found there told me that Matheson was “a disgrace to our party.” I also attended a meeting of the Utah Democrats education caucus, where Matheson was the featured guest. One of the organizers, teacher Robert Comstock, had actually helped to orchestrate a primary challenge to Matheson in 2010. This year, though, everything had changed, in large part because of the redistricting, which Comstock called “an abomination.”

“In Utah, we are the minority party,” he told me. “We’ve got to keep this seat. In my heart I know [Matheson] cares about our values.”

By switching parties, the way many conservative Dems have done in years past, Matheson could have an easier go of things. Why isn’t he just a moderate Republican, I asked him? “I’m part of a party that I think values making sure that everyone in this country has an opportunity to succeed,” he responded. “That’s why I’m a Democrat.” It’s clear, too, that a party switch might not even save him. Matheson observes that moderation is risky business in politics these days, a point driven home by the fate of former Utah Sen. Robert Bennett, a moderate Republican who was capable of working with Democrats. In 2010, tea party activists ousted Bennett in a primary challenge that sounded the death knell for bipartisanship in the state.

This year, Matheson is fighting those same forces, which have aligned heavily behind Love. And Matheson has worked to highlight the hardline agenda Love has embraced, particularly on education, where the GOP candidate has proposed to abolish special education funding, Pell grants, the student loan program, and the school lunch program.

Matheson is putting his faith in his belief that Utah voters are more independent than they get credit for. “A lot of people say they vote the person not the party,” he says. “But in Utah, they really do or I wouldn’t be here.”