When Charlton Heston said the federal government could take his guns from his "cold, dead hands," he was referring to the ATF.Preston Mack/ZUMAPress

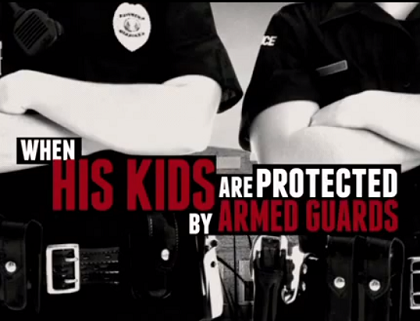

Driven to act by last month’s massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, President Barack Obama on Wednesday called on Congress to pass new laws banning assault weapons and high-capacity magazines and targeting gun traffickers, and he announced 23 steps his administration is taking to better enforce existing law. With Republicans threatening to block any legislation—and some extreme GOPers calling for impeachment if Obama acts alone—reform, as could be expected, will not be easy.

But should Obama gets what he wants, he’ll face another major challenge: his own Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. Over the last three decades, gun activists and lawmakers have purposefully hindered the ATF and carefully molded the agency that enforces gun laws to serve their own interests, stunting the ATF’s budget, handicapping its regulatory authority, and keeping it effectively leaderless. The bureau Obama is counting on to lead his gun control push is a disaster…by Republican design.

The problems are obvious. The agency that Obama said “works most closely with state and local law enforcement to keep illegal guns out of the hands of criminals” has the same of number of agents as the Phoenix Police Department. Its budget has barely budged in decades (as the Department of Homeland Security has grown flush with post-9/11 funding). It has fewer investigators than it did in 1973. And its acting (and part-time) director, B. Todd Jones, commutes to work from Minneapolis, where he works full-time as a US attorney. It hasn’t had a permanent director for six years. The NRA blocked Obama’s earlier appointee, Andrew Traver, in part because Traver had once attended a meeting of police chiefs that focused on gun control. At the unveiling of his gun violence prevention package, Obama announced he would seek to make Jones the permanent (and presumably fulltime) chief of the ATF.

To understand how the ATF became the weakest of law enforcement agencies, you have to go back to President Ronald Reagan’s first term.

The 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, the first major piece of gun control legislation since the Capone days, led the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division of the Department of the Treasury to sprout a third responsibility: handguns. With the market for moonshine collapsed—due to a global spike in sugar prices—the division’s primary investigative responsibility for most of its history withered. The new mandate to regulate arms sales filled the void. It also made the bureau a natural foil for the nascent gun lobby, and the NRA, whose leadership was fast transitioning from a moderate coalition of sportsmen to a band of true believers, went to work to make the agency a pariah.

Republicans and Democrats alike hammered the agency for years. Appearing in a 1981 NRA-produced film, Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.) charged, “If I were to select a jackbooted group of fascists who are perhaps as large a danger to American society as I could pick today, I would pick BATF.” A 1982 Senate report blasted the agency’s supposed “practically reprehensible” enforcement tactics.

Leading the charge was Reagan. On the campaign trail, he’d bashed the ATF and vowed to dissolve it. Once in Washington, Reagan, with the NRA’s backing, proposed folding the ATF into the Secret Service—the two branches of the Treasury most unlike all the others. ATF agents would help the Secret Service handle its beefed-up responsibilities of campaign years and expand its investigative powers. It would have been a death sentence for the bureau.

But then the NRA had had a change of heart. The organization’s strategists came to worry that if gun law enforcement was handed to the Secret Service, one of the few federal agencies with a reputation for competence, gun owners might actually have something to fear. And, they feared, that if the agency did become part of the Secret Service, they’d lose an easy target.

The NRA realized, “‘Oh my God, we’re gonna lose the ATF!'” recalls William Vizzard, a professor of criminology at California State University-Sacramento, who worked for bureau at the time. “It would have been like removing the Soviets during the Cold War, for the Defense Department—there’s nobody to point to.”

Working in conjunction with the liquor lobby (which had its own misgivings about suddenly being regulated by the Customs Service), the NRA coaxed a friendly lawmaker, Sen. James Abdnor (R-S.D.), into scuttling the merger by inserting language in a budget bill. As Vizzard puts it, “If it weren’t for the NRA and the liquor industry, there would be no ATF today, because the merger with the Secret Service would have just gone ahead.”

Once the NRA had saved the ATF, it focused on how to neuter it. Four years after bargaining for the preservation of the ATF, the NRA helped Congress formally handcuff the agency, in the form of the 1986 Firearms Owners Protection Act. The law, which included a handful of token regulations (such as a ban on machine guns), made it all but impossible for the government to prosecute corrupt gun dealers. It prohibited the bureau from compiling a national database of retail firearm sales, reduced the penalty for dealers who falsified sales records from a felony to a misdemeanor, and raised the threshold for prosecution for unlicensed dealing.

Perhaps most glaringly, the ATF was explicitly prohibited from conducting more than one inspection of a single dealer in a given year, meaning that once an agent had visited a shop, that dealer was free to flout the law.

Those restrictions haven’t changed over the last two decades. “There’s no other law enforcement entity in the country that has any restriction remotely like that,” says Jon Lowy, the director of the legal action project at the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

But the NRA wasn’t done; over the next decade-and-a-half, it worked with Congress to run up the score. Following the joint ATF and FBI raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, in 1993—which NRA executive vice president Wayne LaPierre said was “reminiscent of the standoff at the Warsaw ghetto”—Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) launched a Firearms Legislation Task Force to hold hearings on perceived ATF abuses. His deputy, Rep. Bob Barr (R-Ga.), called for the bureau to be disbanded. LaPierre, channeling Dingell, called ATF agents to “jackbooted thugs,” prompting former president George H.W. Bush to resign his NRA membership.

During the George W. Bush administration, The gun lobby delivered another big blow. In 2003, Rep. Todd Tiahrt (R-Kan.) inserted a series of amendments into a Department of Justice appropriations bill that prohibited the ATF from sharing information on weapons traces to the general public—effectively restricting researchers from detecting trends and potential loopholes in current policy. (A 1996 NRA-backed budget likewise prohibited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from studying the health effects of gun ownership.)

The same year, Congress, backed by the NRA, split the ATF off from the Department of Treasury and stipulated that its director be confirmed by the Senate, effectively giving the gun lobby veto power over who would run the agency. Since then, the ATF has simply gone leaderless. No nominee has been confirmed by the Senate after that policy went into effect—not even President Bush’s pick. Without job security, acting ATF directors have had none of the political capital needed to reform the agency or run it at full throttle.

And the hits have kept on coming. Last year’s “Fast and Furious” gun-walking scandal caused yet another interim director to resign under pressure from gun rights activists and shed light into cases of corruption and depreciating morale at the bureau. LaPierre and Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) alleged a conspiracy on the part of the ATF and the White House to use Fast and Furious to push FOR massive arms confiscation. Around the same time, Fox News analyst Dick Morris typified a resurgent line of 1990s thinking when he all but justified the murder of federal agents: “Those crazies in Montana who say, ‘We’re going to kill ATF agents because the UN’s going to take over’—well, they’re beginning to have a case.”

The ATF’s challenges haven’t gone overlooked by the White House. In his remarks Wednesday afternoon, Obama outlined the urgency of making Jones a full-time director. He’s right; the rest of his agenda just might depend on it.