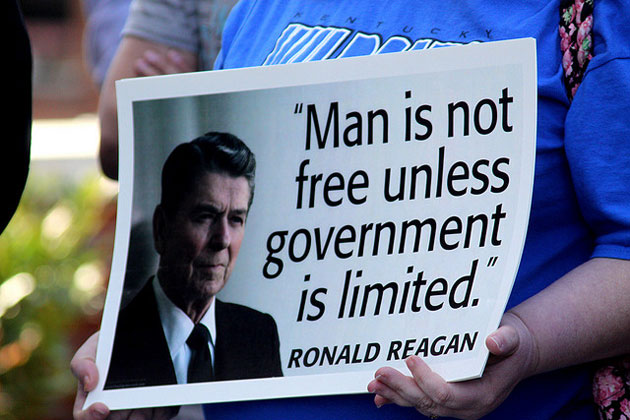

Sign supporting limited government at a Tea Party in London, Kentucky.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/22007612@N05/4469679258/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

After a grueling election cycle from which the GOP emerged with a net loss of eight seats in the House, two seats in the Senate, and no White House, one might expect Republicans to reconsider their view that the electorate has given a solid mandate to conservative hardliners. But no: From the fiscal cliff talks (where only 29 percent of Americans approve of the work GOP leaders have done), to the inflexible stance on guns post-Sandy Hook amid an eight year high in public calls for better gun control, the party seems to be largely in denial about where the policy mandate lies. And that, in turn, highlights a longer-term problem: The right-wing base is less vital than it used to be. The challenge can be seen most evidently in a movement I know from personal experience: the religious right.

To be sure, the movement remains a major player. The politically active core of the conservative Christian block, white evangelicals, still compose 26 percent of the voting population nationally, equal to the portion of African-American, Asian, and Hispanic voters combined and they are up 3 percent from their 2004 numbers. Just 30 percent of those voters cast their ballot for Obama this past November (compared to Clinton’s 36 percent in 1996, and Jimmy Carter’s whopping 41 percent in 1976).

However, let’s take a look at another fact: evangelicals have increased primarily in their strategic strongholds. In Iowa and Ohio, the white evangelical voting population went up by 5 percent from 2004. The South is as (if not more) evangelical as ever, most notably in Mississippi, where white evangelicals increased by 2 percent from 2004 to 2012, going to a whopping 50 percent of the entire voting population and Alabama, where white evangelical voters went up by 4 percent.

During primary season, evangelicals often make up the majority of Republican voters in these states. In my home state of Georgia, for instance, 68 percent of Republican voters were evangelical. In Alabama, the figure was 80 percent. Florida: 47 percent. Iowa: 57 percent. And in Ohio, evangelicals made up 49 percent of Republican primary voters.

On the other hand, both the number of evangelicals and Protestants as a whole has decreased in several states, notably by 4.5 percent in both Maine and Wisconsin since 2004—a potential factor in the success of marriage equality on the ballot this year.

In a word, the religious right seems to be staying very strong where it has long been strong, and declining or failing to make inroads beyond those places. That’s a recipe for stagnation. And that trend is just one part of a bigger problem that affects the New Right coalition on a larger scale.

While conservative ideologues might remain popular within the Republican Party, they’re getting pummeled in the message war nationally. Approval of Republican Congressional leaders is 7 percent lower than approval of their Democratic counterparts, and stands at its lowest point since 2009. Likewise, 64 percent of Americans favor taxing the wealthiest, 54 percent support limiting tax write-offs for large corporations, and a majority of Americans disapprove of reducing federal funding for Medicare, healthcare, education, student loans, and low-income assistance programs, all while a majority of Republican voters support cuts in all of these programs.

What’s going on here? Part of the problem is that the New Right coalition relies on the same ideas based on the same people it has relied on since the 1960s and 1980s. The Heritage Foundation and National Review ideology that underlies modern conservative politics starts with Goldwater and ends with Reagan. Leaders of the party regularly kiss the proverbial ring: they make documentaries (a la Newt Gingrich’s Citizen’s United-produced documentary on Reagan), write books (think Dinesh D’Souza’s Reagan book), and even produce radio spots featuring Reagan (e.g. every Heritage ad on talk radio, ever.)

When I thought I could be some sort of strange child pundit wonder, I wanted to fit in with conservatives so badly that I dedicated both of my books to the holy trinity of Reagan, Goldwater, and Buckley. And I’d never even read Conscience of a Conservative, much less a single issue of National Review! But actually knowing what they thought meant nothing; mentioning their names seemed enough to make you a part of their club. My exposure to politics had centered on talk radio (and online commentary from talk-radio hosts), so I can say from experience how little research many of today’s conservatives put into forming their opinions.

This brings me to another reason why conservatives keep losing the message war: the messenger. Up until about the ‘90s, academic/intellectual types like Buckley and Brent Bozell led the charge with magazines, books, and appearances on shows like Crossfire. Nowadays, the more visible members of the conservative intelligentsia are talk show hosts, TV presenters, and opinion writers—Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, Bill O’Reilly, and Sean Hannity.

In recent years, there has been an attempt to put a more populist face on these ideologues’ fanatical calls for small government, with corporate donors and political operatives focusing on building up the Tea Party movement. But after scoring great gains for Republicans in 2010, the Tea Party wasn’t able to maintain momentum: Here, too, the appeal is mainly in places that are already strongly Republican, the South and certain areas of the Midwest.

From my own experience in the modern conservative coalition, including growing up in an extremely conservative Southern evangelical household, I know that the base will remain strong in certain areas without any need to moderate its views. However, your base alone can’t win elections.

The Right, like any other political movement, finds itself every now and then at a point where it needs to reevaluate itself. Today, too many in the GOP don’t want to admit that they’ve lost any policy mandate they might have had in 2010. Until they do—listening to some of their own leaders, like Jeb Bush—they are doomed to stay in the current state of stagnation.

At the last minute, Grover Norquist agreed that the Senate’s fiscal cliff compromise was an acceptable solution. However this support of compromise from the economic far-right would last only a few hours, until the Club for Growth told Republicans in the House they must vote “no” on the compromise; a bill which the group reasoned was simply “business as usual,” adding that the only reason the Senate passed the bill so late at night was “in the hopes of avoiding public scrutiny” rather than gridlock and political maneuvering. The far right found its champion in the Senate with Sen. Marco Rubio, who voted “no,” arguing that it was a matter of principle and not politics.

What the Tea Party-backed senator realized was that if he wants to have any chance of winning the nomination in 2016 he’ll have to cater to the hard right. And if Rubio’s calculations are any indication, this means relatively little moderation for the party in the short run.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. A more modern conservative coalition would broaden the base and bring in new leaders—exchanging the “intense policy demanders” like the National Rifle Association for those promoting innovative policies on issues where conservatives are losing (gay marriage, gun control, taxing the wealthy). The problem is that given the strength of conservative voters in the primary electorate, most less-extreme candidates don’t stand much of a chance. And while some in the old guard have tested the waters with moves such as David Keene’s inclusion of the gay Republican group GOProud to the Conservative Political Action Conference, it will be the next generation of Republican leaders who determine whether the party of Reagan is ready to move past the ‘80s and come to terms with a changing America.