Weeks after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary that left 20 children and six teachers dead, the American public is still demanding that lawmakers say how they plan to stop future gun violence. One anti-gun measure that is picking up steam is community gun buyback programs, where people can turn weapons into the police for a couple hundred bucks or shopping discounts. These events have already been going on for years, but in the last week alone, at least six cities have scheduled new buybacks. Proponents say that they get guns off the streets and slash local crime rates. But critics point out that coaxing people into selling their weapons for cheaper groceries won’t do much to stop mass shootings.

“It would be hard to imagine a shooter like Adam Lanza not being able to obtain a weapon because of a local gun buyback program,” says Ladd Everitt, spokesman for the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. “Lanza’s Bushmaster was purchased legally.” (By his mother, Nancy.) Everitt also points out that the number of guns bought in these events is “piddling” compared to the number of guns in the United States. “It’s just not going to make a dent.”

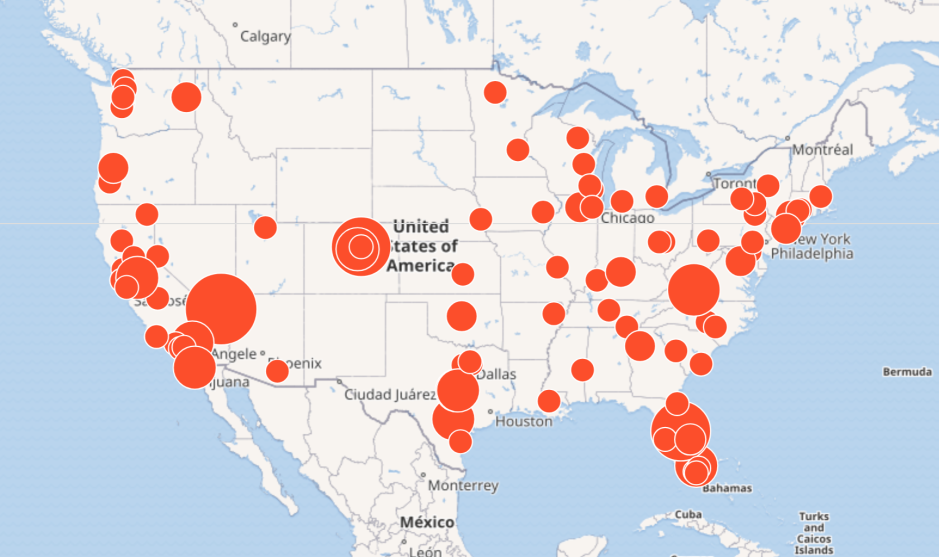

Since Newtown, there have been at least 27 buybacks held or planned. The shooting appears to have had an impact on cities’ decisions to hold gun buyback events as well as people’s decision to turn up. The largest buyback, which took place in Los Angeles, was scheduled for an earlier date because of the shooting; it ended up netting over 2,000 firearms. A buyback in New Albany, Indiana, held two weeks after Newtown, was so popular that $50,000 in buyback funds were spent in 90 minutes. New buyback events were scheduled in Ithaca, New York, Pueblo, Colorado, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Piedmont, California, because of Newtown. And places that scheduled gun buybacks before the mass shooting, like Oakland, San Francisco, and Camden, New Jersey, saw record numbers of guns turned in.

Gun buyback programs have even drawn the attention of federal lawmakers. Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) cowrote a letter with Rep. Ted Deutch (D-Fla.) on December 21 requesting that $200 million in federal funds be set aside for gun buyback programs in the fiscal cliff deal. George Burke, a spokesman for Connolly’s office, told Mother Jones that increasing funding could go a long way towards encouraging communities to start new buyback programs. Buybacks, which can cost in the tens of thousands of dollars, are usually funded by eclectic sources, ranging from supermarkets to state criminal forfeiture funds to, in one case, a medical marijuana group.

City officials remain enthusiastic that these events work. The Los Angeles Police Department claims violent crime has decreased 33 percent since the city’s buyback program began in 2009. Lester Davis, a spokesman for the Baltimore City Council, says that buybacks “take dangerous weapons off the street” and pointed to a buyback on December 15 as an example. “We received more than a dozen firearms that violated federal statues,” he says.

But experts argue that all this political momentum could be better directed elsewhere. A 2004 report released by the National Research Council found that the theory underlying gun buybacks is “badly flawed” for an obvious reason: Criminals who actively acquire guns generally don’t want to give them to the police department to destroy, even if it’s done anonymously. Neither do pro-gun types, who tend to vehemently oppose the events. After a July buyback in Chicago, a pro-gun group called Guns Save Life sold old, junk weapons and used the earnings to fund a shooting camp for kids. As Daniel Polsby, dean of the George Mason University School of Law points out, it’s “silly” to think that “making a market in a commodity will make that commodity scarcer.”

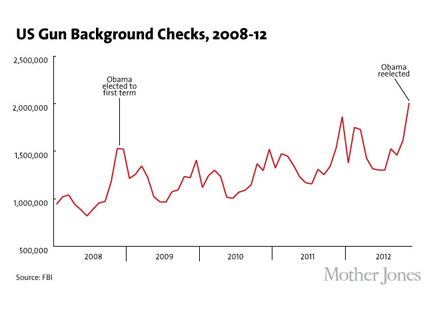

Jon Vernick, codirector of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research, told the Daily Beast that gun buybacks are a political cop-out. While buybacks give communities “a visible thing to do” after mass shootings occur, he said that “conducting buybacks is much easier than fighting the political battle.” And as illustrated in this chart, Congress can’t even get that accomplished. Although Connolly’s letter had the support of more than 40 House members, it ultimately wasn’t included in the deal, as “many Republicans were not conducive to the provision,” according to Burke.

Burke adds that he doesn’t view gun buybacks as “the be-all end-all” to stopping mass shootings, but says that “you want to do everything you can to minimize gun violence, and this is one piece of the puzzle.”

While a national gun buyback program isn’t on the table for now, if you want to see what one might look like, head down under. Australia, which saw several mass shootings in both the ’80s and ’90s, successfully bought back and destroyed 650,000 guns after an especially violent shooting in Tasmania in 1996, effectively ending mass shootings in the country. There was one tiny difference: The buyback was mandatory.