Arrowhead Marsh near Oakland could turn to mud by 2080. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/taylar/4029881809/sizes/l/in/photostream/">ingridtaylar</a>/Flickr

By now, we’re used to hearing about the threats sea level rise poses to human society: It can wash away urban areas, give a boost to storms, and swallow island nations. But new research from a team at the US Geological Survey shows that rising seas can also devastate fragile ecosystems.

Using a custom-built sea level modeling tool, USGS’s Western Ecological Research Center forecast the future for a dozen salt marshes in the San Francisco Bay Area, home to several species of federally protected birds and other animals. The predictions are grim: 95 percent of the marsh area could become mudflats by 2100, the effect of four feet of sea level rise (a level projected by previous studies). That’s a problem for marsh-loving endangered species like the salt marsh harvest mouse (left) and the California black rail bird, both found only in the Bay Area, and for other beach-dwelling birds that count on solid ground to lay their nests.

Take a look at the video below, which shows the projection for a marsh in San Pablo Bay; yellow is land, light blue is average sea level, and dark blue is high water level:

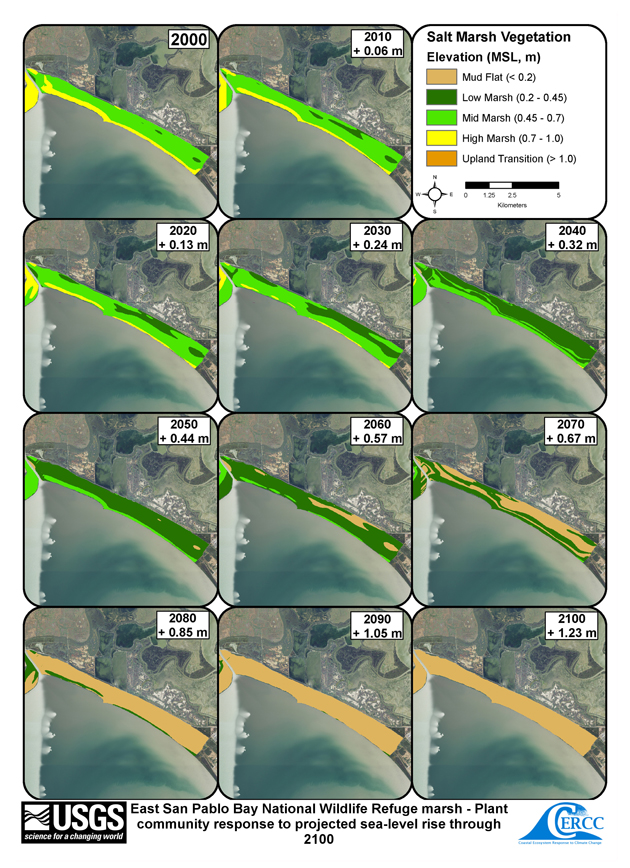

By the end, no more marsh (have a favorite Bay Area marsh? You can see projections for it here). Here’s that same story, told a different way, as the marsh goes from a healthy green to muddy brown:

The study points out that marshes have historically been able to keep pace with sea level rise, by continually accumulating sediment and plant life. They can also escape rising seas by retreating inland. But in the Bay Area many marshes are hemmed in by development, and the rate of sea level rise projected for the remainder of this century could outpace their ability to keep up. By century’s end, the study predicts, the unique “high” marsh habitat—marked by infrequent flooding, relatively solid ground, and hardier plants—could be lost completely, replaced by watery expanses of mud interspersed with a few “low” marshes, bathed in warm salty water and suitable only for algae. This isn’t a problem only for the flora and fauna there: Marshes serve as an important buffer zone between the sea and urban areas; in San Francisco, a lot of important infrastructure (highways, airports, etc.) are only a few feet above sea level.

John Takekawa, who led the study, said the findings make an important statement about the damage sea level rise can bring even when it doesn’t cover the coast.

“Even when it’s not that entire areas will be washed away, per se,” he said, “the vegetation is changing, and then the habitat.”