Growing or shedding a white winter coat at the wrong time is a monster liability for snowshoe hares:Photo by <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/starrydude/">ringsofstaurnrock</a> | Samuel George at <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/starrydude/5604698863/">Flickr</a>.

Snowshoe hares live or die by their coat color—turning brown in the growing season and white in the winter. But the timing of the snow is changing faster than some hares can keep up.

The authors of a new paper in PNAS report that natural populations of North American snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) exposed to three years of widely varying snowpack (2009, 2011, 2012) seemed able to adapt to some extent to changes in spring snow melt dates by changing how quickly they molted from white fur to brown, depending on the presence or absence of snow. But they couldn’t change the speed of their autumn molt from brown to white. That’s because the fall molt appears to be purely a response to the shortening days and unrelated to the appearance of actual snow.

“On average, it takes about 40 days for a hare to completely change from brown to white,” says lead author L. Scott Mills, at the University of Montana College of Forestry and Conservation. “The white-to-brown change takes a few days longer and shows some ability to speed up or slow down according to temperature or snow.”

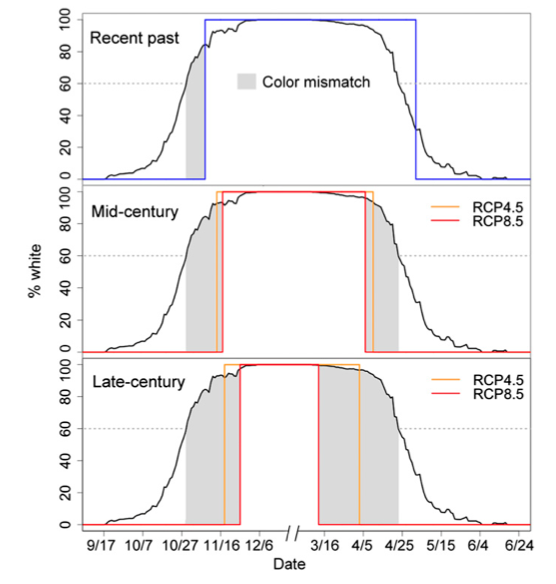

Beyond these findings, the researchers also used an ensemble of climate change projections to predict how changing snow dates might affect hares in the future. Their results suggest that by 2050 there’ll be between 29 and 35 fewer days of snow cover, and by 2100 40 to 69 fewer days. That means hares might be hopping on a mismatched background for four to eight times as many days as they do now.

The future of these hares may boil down to plasticity: the ability of a plant or animal to change its appearance in response to changes in the environment. The authors write:

For example, male rock ptarmigan exhibit behavioral plasticity to reduce conspicuousness by soiling their white plumage after their mates begin egg laying in spring, a phenomenon likely underlain by tradeoffs between sexual selection and predation risk. A more direct avenue for plasticity to reduce mismatch when confronted by reduced snow duration would arise from plasticity in the initiation date or the rate of the seasonal coat color molts. It is not known how much plasticity exists in these traits, nor how much seasonal color mismatch is expected in the future as snow cover lasts a shorter time in the fall and spring.

Snowshoe hares are the main dinner course for the endangered Canadian lynx, which also inhabits the US. So the hares’ ability to adapt or not could fatten lynx in the short term but, as their population declines, leave the cats starving in the future.

At least nine other widely distributed mammals also undergo seasonal color changes: Arctic foxes, collared lemmings, long-tailed weasels, stoats, mountain hares, Arctic hares, white-tailed jackrabbits, and Siberian hamsters. Their ability to match coat color to coming changes in snow cover could determine their fates—and might serve as a lesson for us. As the authors conclude:

The compelling image of a white animal on a brown snowless background can be a poster child for both educational outreach and for profound scientific inquiry into fitness consequences, mechanisms of seasonal coat color change, and the potential for rapid local adaptation.