This week, New York City is defending itself against a lawsuit that claims its controversial “stop and frisk” policy is used to illegally detain and search people on the basis of race. The subject of an ongoing trial, the suit also argues that the weak justifications given by NYPD officers for most stop-and-frisks fail to meet the constitutional burden for search and seizure. We put together this explainer and some charts to help you make sense of what’s going on.

What is “stop and frisk,” exactly, and what does it have to do with the NYPD? Starting in the 1970s, in the hope of curbing street crime, New York City began encouraging its officers to stop people they deem suspicious, to question them, and, if there is adequate reason to suspect illegal activities, to pat them down for things like drugs and weapons. This type of police activity has been upheld in the past: In a landmark 1968 case, Terry v. Ohio, a police officer detained three men without a warrant, suspicious that they were casing a local convenience store for a hold-up. One of the men had a revolver, and the Supreme Court ruled that the warrantless search was constitutional because the cop had reasonable suspicion to believe the men were about to commit a crime.

If it’s constitutional, then what’s the problem? Well, it’s not always constitutional. It’s only constitutional when the police have reasonable suspicion to believe someone poses a danger, has committed a crime, or is preparing to commit one. And police cannot use race as a criterion for any search and seizure. But New York City has faced allegations of unconstitutional policing against communities of color for a long time.

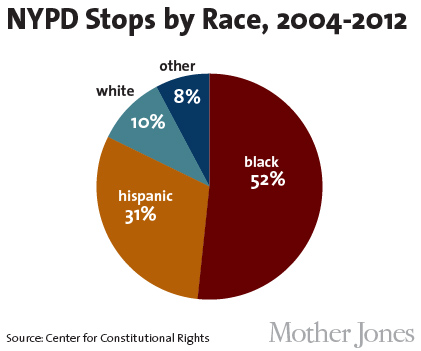

In 1999, the state Attorney General’s Office found that while blacks and Latinos made up about 50 percent of the city’s population, they accounted for 84 percent of the police stops (PDF). The same year, in the aftermath of the slaying of Amadou Diallo, the unarmed Guinean immigrant who was shot 41 times by New York City police, the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) sued the city, alleging that stop-and-frisk was unconstitutional. In a settlement, the NYPD promised it would keep close tabs on who it stops and why.

What’s up with this new lawsuit? In 2008, the Center for Constitutional Rights filed another suit based in part on the data that the NYPD had disclosed since the prior settlement. The case, Floyd et al. v. New York et al., is named for one of the plaintiffs, David Floyd, a 33-year-old Bronx resident and medical student who was stopped and frisked twice by New York police—in one instance after crossing the street to avoid another stop-and-frisk in progress. “It’s a scary thing,” he told Colorlines in March. “You don’t know what’s going to happen with your life, you don’t know what’s going to happen with your freedom.”

The earlier settlement has provided CCR with the statistical ammunition it needs to argue that the NYPD’s policy, which Commissioner Ray Kelly and Mayor Michael Bloomberg have credited with driving down the crime rate, is little more than an excuse to treat New Yorkers as suspects on the basis of race. “This trial is coming at a moment when there is widespread community outrage with NYPD practices,” says Baher Azmy, the group’s legal director. “This is stemming from years and years of perceived harassment and unfair treatment and discriminatory treatment, particularly of minority communities.”

Do stop-and-frisks work? Depends on what you think they’re supposed to do. The justifications most often cited by police officers, according to the data disclosures, were that the individual they stopped was in a “high crime area” or was engaging in “furtive movements.” The lawsuit argues that these are little more than thinly veiled pretexts for racial profiling. These charts will help you visualize the issue. For instance, violent crime in New York City has remained low for years and is still in modest decline (here’s one possible explanation), whereas stops by the NYPD have skyrocketed.

Not every stop results in a frisk, but stops and frisks are increasing at similar rates:

Whether or not the tactic is accomplishing the city’s goals is a matter of opinion. In early April, during the trial, New York state Sen. Eric Adams testified that Commissioner Kelly had once told legislators that the stop-and-frisk program focused on black and Hispanic men because “he wanted to instill fear in them, every time they leave their home they could be stopped by the police.” Kelly told reporters that this was “absolutely, categorically untrue.” But one thing’s certain: The burden of the policy weighs most heavily on black and Hispanic New Yorkers.

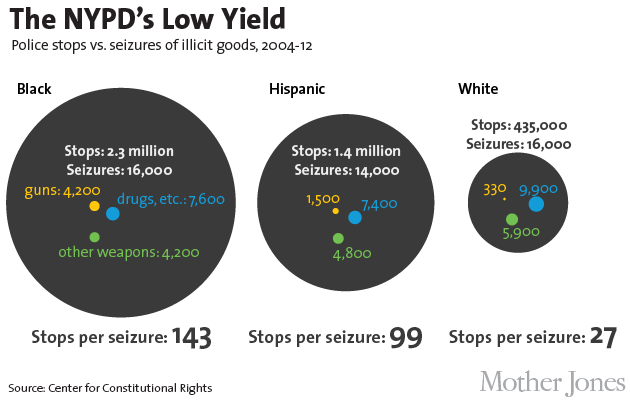

NYPD officer Pedro Serrano, who says he himself has been stopped by the police while off duty, testified that officers were expected to fill quotas that forced them to make more stops than they would have otherwise. Serrano also made a secret recording of a superior stating that “the right people” were to be stopped, which seems to validate claims of racial profiling—but the NYPD’s defenders say the statement was taken out of context.The rising number of stops in recent years has not led to a bounty of illicit goods. Only a very small percentage of the searches lead to a discovery of weapons, drugs, or stolen items. And lo and behold, and as this chart demonstrates, black New Yorkers are far more likely than whites to be stopped needlessly.

In any case, trial judge Shira Scheindlin has said that “the effectiveness of the policy is not of interest to this court.” Her decision will hinge solely upon whether the city’s lawyers can effectively counter CCR’s claims that the NYPD is violating the Constitution. Other police jurisdictions have implemented their own versions of stop-and-frisk, so the trial outcome could affect police practices elsewhere. No matter what happens, the practices of the NYPD and freedom of movement in the city of New York will be affected.

The trial is expected to last another two weeks, and the judge’s decision could follow at any time. We’ll keep you posted.