Donkey: Shutterstock; Houses: Shutterstock

Last week, President Barack Obama laid out his new housing plan, emphasizing the importance of safe, simple, affordable mortgages. But lawmakers in his own party are working against him, trying to gut historic new safeguards on home loans.

A new mortgage rule issued by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) that takes effect January 1 limits fees on new home loans to three percent. The regulation is “one of the most direct and important responses to the mortgage crisis,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) argued in a recent editorial in American Banker. But 12 House Democrats and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) have joined with Republicans to cosponsor bills that would eviscerate the new cap and clear the way for lenders to steer Americans into riskier, higher-cost loans.

The CFPB’s new mortgage rule is intended to prevent lenders from directing borrowers toward higher-cost loans that earn the lenders more money—a practice that helped lead to the financial crisis. Tens of thousands of borrowers, especially minorities, were sold costly subprime loans even when they qualified for more affordable loans, because those loans were more profitable for lenders and brokers, according to a 2011 investigation by the Justice Department. The three percent fee cap effectively ends that conflict of interest.

The new mortgage fee cap also says that fees for certain types of title insurance—which protects the value of a homeowner’s property in case of losses due to defects in the property title—have to be included in the 3 percent cap, to avoid another conflict of interest. In most real estate deals, the lender shops for title insurance for the borrower. If the lender’s company also owns a title insurance company, the lender has an incentive to buy expensive title insurance for the homeowner from that company, since it would benefit his business.

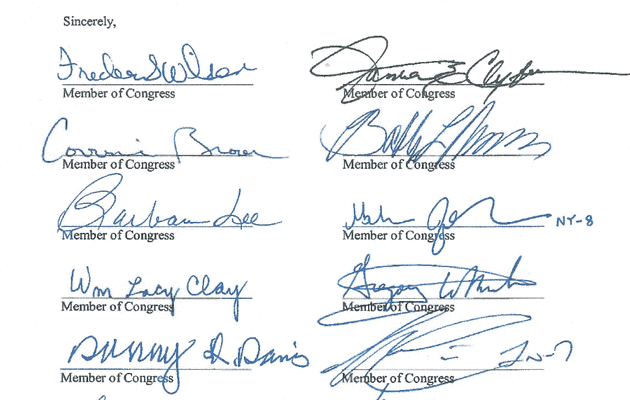

The whole point of the CFPB rule is “to make sure that brokers are more likely to work in the interest of homeowners,” says Alys Cohen, a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC). The bills—backed by Democratic Reps. Gregory Meeks (D-N.Y.), William Lacy Clay (D-Mo.), Gary Peters (D-Mich.), David Scott (D-Ga.), Mike Quigley (D-Ill.), Bill Owens (D-N.Y.), Sanford Bishop (D-Ga.), Gene Green (D-Texas), Jim Matheson (D-Utah), Filemon Vela (D-Texas), Sheila Jackson-Lee (D-Texas), and David Loebsack (D-Iowa)—could re-create the pre-crisis state of affairs.

“Risky and often predatory, high-cost mortgages were a central cause of the financial crisis,” says Micah Hauptman, a financial policy counsel at the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. “It’s shocking that lawmakers are so willing to return to an era in which those types of products thrive.”

Manchin and most of the House Dems did not respond to requests for comment on why they’re backing the bills. Meeks, the only lawmaker to respond, argues that the perverse pre-crisis incentives to steer borrowers into more expensive loans are now “banned” by the CFPB, and adds that regulations on title insurance aren’t needed because it is “regulated at the state level.”

Consumer advocates say Meeks’ reasoning is flawed because although other CFPB rules limit lenders’ ability to steer borrowers into more expensive loans, they do not fully ban the practice. And NCLC’s Cohen explains that regulation of title insurance at the state level is notoriously lax. Title insurance is generally vastly more expensive than other types of insurance. (The CFPB says it does not comment on proposed legislation.)

Meeks also contends that the bill he cosponsored is necessary in order to ensure that low-income borrowers have access to affordable home loans. But Warren and Waters say this rationalization is played out. “We heard these same arguments in the early 2000s as the industry lobbied against consumer protection,” the lawmakers wrote in the American Banker editorial. “And the result was that needed reforms were not made until after a financial crisis that nearly brought down the economy.”

“It is not surprising that industry participants want to return to a period in which they can peddle products that are cash cows,” Hauptman says. “But it is surprising that members of Congress, from both parties, haven’t learned the fundamental lessons of the crisis, and are seeking to help industry, at the expense of many of their constituents.”

Perhaps it’s not that surprising. In the last election cycle, the 13 Democratic cosponsors of the bills received a total of $628,803 from the real estate industry, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, and $460,441 from the banking sector.