<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&search_tracking_id=VzrPufd2LeoKH1eWUF6uyA&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=hand+covering+eye+scary&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=129506198&src=_k_qSB3Tpj8JRSppyA6yjQ-1-15">DJTaylor</a>/Flickr

This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

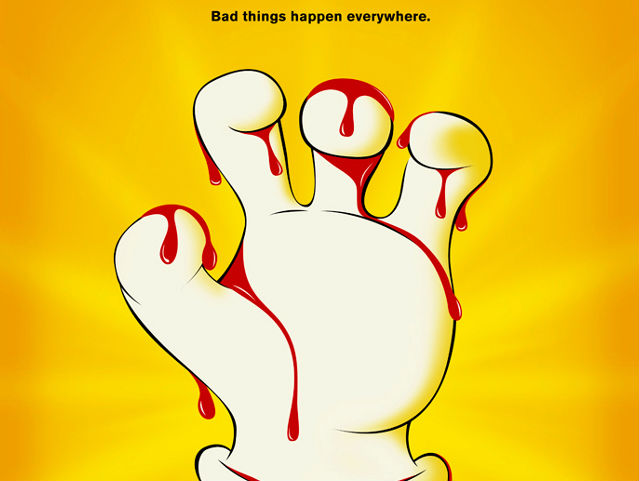

From the time I was little, I went to the movies. They were my escape, with one exception from which I invariably had to escape. I couldn’t sit through any movie where something or someone threatened to jump out at me with the intent to harm. In such situations, I was incapable of enjoying being scared and there seemed to be no remedy for it. When Jaws came out in 1975, I decided that, at age 31, having avoided such movies for years, I was old enough to take it. One tag line in ads for that film was: “Don’t go in the water.” Of the millions who watched Jaws and outlasted the voracious great white shark until the lights came back on, I was that rarity: I didn’t. I really couldn’t go back in the ocean—not for several years.

![]() I don’t want you to think for a second that this represents some kind of elevated moral position on violence or horror; it’s a visceral reaction. I actually wanted to see the baby monster in Alien burst out of that human stomach. I just knew I couldn’t take it. In all my years of viewing (and avoidance), only once did I find a solution to the problem. In the early 1990s, a period when I wrote on children’s culture, Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park sparked a dinosaur fad. I had been a dino-nerd of the 1950s and so promised Harper’s Magazine a piece on the craze and the then-being-remodeled dino-wing of New York’s American Museum of Natural History. (Don’t ask me why that essay never appeared. I took scads of notes, interviewed copious scientists at the museum, spent time alone with an Allosaurus skull, did just about everything a writer should do to produce such a piece—except write it. Call it my one memorable case of writer’s block.)

I don’t want you to think for a second that this represents some kind of elevated moral position on violence or horror; it’s a visceral reaction. I actually wanted to see the baby monster in Alien burst out of that human stomach. I just knew I couldn’t take it. In all my years of viewing (and avoidance), only once did I find a solution to the problem. In the early 1990s, a period when I wrote on children’s culture, Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park sparked a dinosaur fad. I had been a dino-nerd of the 1950s and so promised Harper’s Magazine a piece on the craze and the then-being-remodeled dino-wing of New York’s American Museum of Natural History. (Don’t ask me why that essay never appeared. I took scads of notes, interviewed copious scientists at the museum, spent time alone with an Allosaurus skull, did just about everything a writer should do to produce such a piece—except write it. Call it my one memorable case of writer’s block.)

My problem was never scaring myself to death on the page. I read Crichton’s novel without a blink. The question was how to see it when, in 1993, it arrived onscreen. My solution was to let my kids go first, then take them back with me. That way, my son could lean over and whisper, “Dad, in maybe 30 seconds the Velociraptor is going to leap out of the grass.” My heart would already be pounding, my eyes half shut, but somehow, cued that way, I became a Crichton vet.

Of course, gazillions of movie viewers have seen similar films with the usual array of sharks, dinosaurs, anacondas, axe murderers, mutants, zombies, vampires, aliens, or serial killers, and done so with remarkable pleasure. They didn’t bolt. They didn’t imagine having heart attacks on the spot. They didn’t find it unbearable. In some way, they liked it, ensuring that such films remain pots of gold for Hollywood to this day. Which means that they—you—are an alien race to me.

The Sharks, Aliens, and Snakes of Our World

This came to mind recently because I started wondering why, when we step out of those movie theaters, our American world doesn’t scare us more. Why doesn’t it make more of us want to jump out of our skins? These days, our screen lives seem an apocalyptic tinge to them, with all those zombie war movies and the like. I’m curious, though: Does what should be deeply disturbing, even apocalyptically terrifying, in the present moment strike many of us as the equivalent of so many movie-made terrors— shivers and fears produced in a world so far beyond us that we can do nothing about them?

I’m not talking, of course, about the things that reach directly for your throat and, in their immediacy, scare the hell out of you—not the sharks who took millions of homes in the foreclosure crisis or the aliens who ate so many jobs in recent years or even the snakes who snatched food stamps from needy Americans. It’s the overarching dystopian picture I’m wondering about. The question is: Are most Americans still in that movie house just waiting for the lights to come back on?

I mean, we’re living in a country that my parents would barely recognize. It has a frozen, riven, shutdown-driven Congress, professionally gerrymandered into incumbency, endlessly lobbied, and seemingly incapable of actually governing. It has a leader whose presidency appears to be imploding before our eyes and whose single accomplishment (according to most pundits), like the website that goes with it, has been unraveling as we watch. Its 1% elections, with their multi-billion dollar campaign seasons and staggering infusions of money from the upper reaches of wealth and corporate life, are less and less anybody’s definition of “democratic.”

And while Washington fiddles, inequality is on the rise, with so much money floating around in the 1% world that millions of dollars are left over to drive the prices of pieces of art into the stratosphere, even as poverty grows and the army of the poor multiplies. And don’t forget that the national infrastructure—all those highways, bridges, sewer systems, and tunnels that were once the unspoken pride of the country—is visibly fraying.

Up-Armoring America

Meanwhile, to the tune of a trillion dollars or more a year, our national treasure has been squandered on the maintenance of a war state, the garrisoning of the planet, and the eternal upgrading of “homeland security.” Think about it: so far in the twenty-first century, the US is the only nation to invade a country not on its border. In fact, it invaded two such countries, launching failed wars in which, when all the costs are in, trillions of dollars will have gone down the drain and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and Afghans, as well as thousands of Americans, will have died. This country has also led the way in creating the rules of the road for global drone assassination campaigns (no small thing now that up to 87 countries are into drone technology); it has turned significant parts of the planet into free-fire zones and, whenever it seemed convenient, obliterated the idea that other countries have something called “national sovereignty”; it has built up its Special Operations forces, tens of thousands of highly trained troops that constitute a secret military within the US military, which are now operational in more than 100 countries and sent into action whenever the White House desires, again with little regard for the sovereignty of other states; it has launched the first set of cyber wars in history (against Iran and its nuclear program), has specialized in kidnapping terror suspects off city streets and in rural backlands globally, and has a near-monopolistic grip on the world arms trade (a 78% market share according to the latest figures available); its military expenditures are greater than the next 13 nations combined; and it continues to build military bases across the planet in a historically unprecedented way.

In the twenty-first century, the power to make war has gravitated ever more decisively into the White House, where the president has a private air force of drones, and two private armies of his own—those special operations types and CIA paramilitaries—to order into battle just about anywhere on the planet. Meanwhile, the real power center in Washington has increasingly come to be located in the national security state (and the allied corporate “complexes” linked to it by that famed “revolving door” somewhere in the nation’s capital). That state within a state has gone through boom times even as many Americans busted. It has experienced a multi-billion-dollar construction bonanza, including the raising of elaborate new headquarters, scores of building complexes, massive storage facilities, and the like, while the private housing market went to hell. With its share of that trillion-dollar national security budget, its many agencies and outfits have been bolstered even as the general economy descended into a seemingly permanent slump.

In the twenty-first century, the power to make war has gravitated ever more decisively into the White House, where the president has a private air force of drones, and two private armies of his own—those special operations types and CIA paramilitaries—to order into battle just about anywhere on the planet. Meanwhile, the real power center in Washington has increasingly come to be located in the national security state (and the allied corporate “complexes” linked to it by that famed “revolving door” somewhere in the nation’s capital). That state within a state has gone through boom times even as many Americans busted. It has experienced a multi-billion-dollar construction bonanza, including the raising of elaborate new headquarters, scores of building complexes, massive storage facilities, and the like, while the private housing market went to hell. With its share of that trillion-dollar national security budget, its many agencies and outfits have been bolstered even as the general economy descended into a seemingly permanent slump.

As everyone is now aware, the security state’s intelligence wing has embedded eyes and ears almost everywhere, online and off, here and around the world. The NSA, the CIA, and other agencies are scooping up just about every imaginable form of human communication, no matter where or in what form it takes place. In the process, American intelligence has “weaponized” the Internet and functionally banished the idea of privacy to some other planet.

Meanwhile, the “Defense” Department has grown ever larger as Washington morphed into a war capital for an unending planetary conflict originally labeled the Global War on Terror. In these years, the “all-volunteer” military has been transformed into something like a foreign legion, another 1% separated from the rest of society. At the same time, the American way of war has been turned into a profit center for a range of warrior corporations and rent-a-gun outfits that enter combat zones with the military, building bases, delivering the mail, and providing food and guard services, among other things.

Domestically, the US has grown more militarized as “security” concerns have been woven into every form of travel, terror fears and alerts have become part and parcel of daily life, and everything around us has up-armored. Police forces across the land, heavily invested in highly militarized SWAT teams, have donned more military-style uniforms, and acquired armored cars, tanks, MRAPS, drones, helicopters, drone submarines, and other military-style weaponry (often surplus equipment donated by the Pentagon). Even campus cops have up-armored.

In a parallel development, Americans have themselves become more heavily armed and in a more military style. Among the 300,000,000 firearms of all sorts estimated to be floating around the US, there are now reportedly three to four million AR-15 military-style assault rifles. And with all of this has gone a certain unhinged quality, both for those SWAT teams that seem to have a nasty habit of breaking into homes armed to the teeth and wounding or killing people accused of nonviolent crimes, and for ordinary citizens who have made random or mass killings regular news events.

On August 1, 1966, a former Marine sniper took to the 28th floor of a tower on the campus of the University of Texas with an M-1 carbine and an automatic shotgun, killing 17, while wounding 32. It was an act that staggered the American imagination, shook the media, led to a commission being formed, and put those SWAT teams in our future. But no one then could have guessed how, from Columbine high school (13 dead, 24 wounded) and Virginia Tech university (32 dead, 17 wounded) to Sandy Hook Elementary School (26 dead, 20 of them children), the unhinged of our heavily armed nation would make slaughters, as well as random killings even by children, all-too-common in schools, workplaces, movie theaters, supermarket parking lots, airports, houses of worship, navy yards, and so on.

And don’t even get me started on imprisonment, a category in which we qualify as the world’s leader with 2.2 million people behind bars, a 500% increase over the last three decades, or the rise of the punitive spirit in this country. That would include the handcuffing of remarkably young children at their schools for minor infractions and a fierce government war on whistleblowers—those, that is, who want to tell us something about what’s going on inside the increasingly secret state that runs our American world and that, in 2011, considered 92 million of the documents it generated so potentially dangerous to outside eyes that it classified them.

A Nameless State (of Mind)

Still, don’t call this America a “police state,” not given what that came to mean in the previous century, nor a “totalitarian” state, given what that meant back then. The truth is that we have no appropriate name, label, or descriptive term for ourselves. Consider that a small sign of just how little we’ve come to grips with what we’re becoming. But you don’t really need a name, do you, not if you’re living it? However nameless it may be, tell me the truth: Doesn’t the direction we’re heading in leave you with the urge to jump out of your skin?

And by the way, what I’ve been describing so far isn’t the apocalyptic part of the story, just the everyday framework for American life in 2013. For your basic apocalypse, you need to turn to a subject that, on the whole, doesn’t much interest Washington or the mainstream media. I’m talking, of course, about climate change or what the nightly news loves to call “extreme weather,” a subject we generally prefer to put on the back burner while we’re hailing the “good news” that the US may prove to be the Saudi Arabia of the twenty-first century—that is, hopped up on fossil fuels for the next 50 years; or that green energy really isn’t worth an Apollo-style program of investment and R&D; or that Arctic waters should be opened to drilling; or that it’s reasonable to bury on the inside pages of the paper with confusing headlines the latest figures on the record levels of carbon dioxide going into the atmosphere and the way the use of coal, the dirtiest of the major fossil fuels, is actually expanding globally; or… but you get the idea. Rising sea levels (see ya, Florida; so long, Boston), spreading disease, intense droughts, wild floods, extreme storms, record fire seasons—I mean, you already know the tune.

You still wanna be scared? Imagine that someone offered you a wager, and let’s be conservative here: continue on your present path and there will be a 10%-20% chance that this planet becomes virtually uninhabitable a century or two from now. Not bad odds, right? Still, I think just about anyone would admit that only a maniac would take such a bet, no matter the odds. Actually, let me amend that: only a maniac or the people who run the planet’s major energy companies, and the governments (our own included) that help fund and advance their activities, and those governments like Russia and Saudi Arabia that are essentially giant energy companies.

Because, hey, realistically speaking, that’s the bet that all of us on planet Earth have taken on.

And just in case you were wondering whether you were still at the movies, you’re not, and the lights aren’t coming back on either.

Now, if that isn’t scary, what is?

Boo!

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture (now also in a Kindle edition), runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. His latest book, co-authored with Nick Turse, is Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook or Tumblr. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return From America’s Wars—The Untold Story.To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.