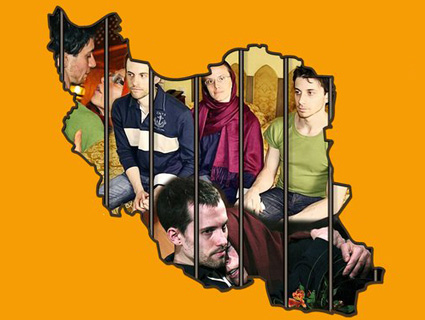

<a href="https://www.facebook.com/FreetheHikers">Free the Hikers</a>/Facebook

It’s hard to find meaning in life when you live in a box. During the 26 months I spent in a political prison in Iran from 2009 to 2011, after being snatched with my friends while hiking, I envied my fellow inmates. I remember discovering that the man in the cell next to mine hadn’t been out of his cell for a week. I was appalled. “It doesn’t matter to me,” he whispered to me. “Being in prison is a road to democracy.” I was struck by this. For him, sitting there all alone was a type of action with a purpose. I wished I could feel that way.

I understand how people become religious in prison, especially in isolation. Without meaning to our lives, we are nothing. I had my own quasi-Christian phase—or rather, quasi-Dostoyevskian phase. As I read The Brothers Karamazov, I dwelled on Father Zosima’s exhortations to Alyosha: “There is only one salvation for you: take yourself up, and make yourself responsible for all the sins of men. For indeed it is so, my friend, and the moment you make yourself sincerely responsible for everything and everyone, you will see at once that it is really so, that it is you who are guilty on behalf of all and for all.” Somehow, in the rabbit hole of my mind, I found a personal message in this story: Even if I wasn’t myself guilty, I could bear the wrongs of others and cleanse them through my own suffering. There was relief in this idea. It made it so that my sitting in a cell meant something.

I didn’t want to admit that I was becoming religious, so I tried to put a rational spin on it. Maybe by detaining us, the Iranian government would release its ire against the US government, which would somehow lead to an easing of hostility. Maybe we were paying for our national sins: for the CIA-backed overthrow of Mossadegh, for supporting Saddam in the Iran-Iraq war, for the sanctions. For a while, believing this, it felt almost good to be in prison.

Like most idiosyncratic lines of thinking I had there (Tolstoy briefly had me believing I had no free will), that one didn’t last long. I eventually saw it for what it was: a delusional, isolation-fueled attempt to find meaning in my own meaningless suffering.

I was reminded of all this a few days ago, when a friend in the United Kingdom sent a link to an Associated Press story outlining the procession of secret negotiations between the United States and Iran that eventually led to the nuclear agreement reached Sunday. My friend tweeted, “None of this may have happened were it not for your hellish experience. Nuts.”

It wasn’t as far-fetched a theory as it may seem. Before our detention, there had been a stalemate in attempts to open US-Iran relations, especially following the brutal repression of the Green Revolution. To our knowledge, there were no face-to-face meetings between Iranian and US officials throughout our detention, making it that much harder to negotiate for our release. Most of the diplomatic work in securing our release ultimately came from Oman.

According to the AP story, it was after taking up our case that the sultan of Oman offered himself as a mediator in US-Iran rapprochement. Following our release, then-UN Ambassador Susan Rice held clandestine “exploratory” meetings with her Iranian counterpart. These led President Obama to send Deputy Secretary of State William Burns and others to meet with Iranian diplomats in Muscat.

When I contacted a diplomatic source involved in the talks, they said Oman had wanted to “expand the scope of the dialogue” beyond our imprisonment when my wife, Sarah Shourd, was released after 13 months, but “both parties were not interested as there was a lot of mistrust.” After Josh Fattal and I were also released, another 13 months later, the Supreme Leader of Iran insisted that the United States should reciprocate by releasing certain Iranian prisoners, the source said.

In early 2013, Oman secured the release of Iranian scientist Mojtaba Atarodi, who was held on charges of sanctions violations for buying scientific equipment from the United States. Oman also negotiated the release of former Iranian diplomat Nosratollah Tajik from the United Kingdom, the source said, after the United States pushed for his extradition. After that, “there was a bit of relief and willingness to explore further.”

Considering all this, I felt Dostoyevsky’s voice, which I had long discredited, coming back. If US-Iran rapprochement had originated in our detention, did this mean those two years were worth it? Did this mean it was good for us to suffer?

But I realize now how dangerous that line of thinking actually is. As a culture, we thrive on stories of struggle with happy endings. These stories can be empowering—and I’m certainly grateful for the way ours turned out—but they are exceptions. People are locked in cages, maimed, raped, executed, and starved every day, and most do not end up better because of these experiences, nor does humanity.

What changes things for the better is action to stop, prevent, and overcome unnecessary suffering. Josh and I didn’t change anything by living in a cell any more than any other innocent person makes the world better by sitting in a cage. The reason our tragedy led to an opening between the United States and Iran was that many people were actively working to end our suffering. To do so, our friends and families had to strive to build a bridge between the US and Iran when the two governments were refusing to do it themselves. Sarah is not a politician and she has no desire to be, but when she was released a year before Josh and me, she made herself into a skilled and unrelenting diplomat, strengthening connections between Oman and the US that ultimately led to these talks. Without all of these people, my time in prison would have been nothing more than time in prison. And just maybe, the US and Iran might still be nowhere near a solution to the nuclear issue.

This post has been revised.