American snowboarder Karly Shorr competes in the women's slopestyle snowboarding qualifying session at the 22nd Winter Olympic Games in Sochi. Valery Sharifulin/ITAR-TASS/ZUMA

The Winter Olympics kicked off yesterday in Sochi, Russia (first up: men’s snowboarding). When Russian President Vladimir Putin pitched Sochi to the games’ organizers back in 2007, he promised there would be “real snow”… a bold claim for a town better known as a seaside summer resort. Sure enough, this week Sochi had highs in the 50s (warmer than the Super Bowl last weekend in New Jersey) and—uh oh—no new snowfall in the town. Conditions are a bit better in the mountains where the ski events take place, and organizers insist the games are ready to speed ahead on a fresh layer of fake snow.

Low snowfall has become a chronic problem for skiers and snowboarders worldwide, which has turned many of them into vocal activists against climate change. President Obama even mentioned snow sports in his major global warming speech last summer, when he said that “mountain communities worry about what smaller snowpacks will mean for tourism.”

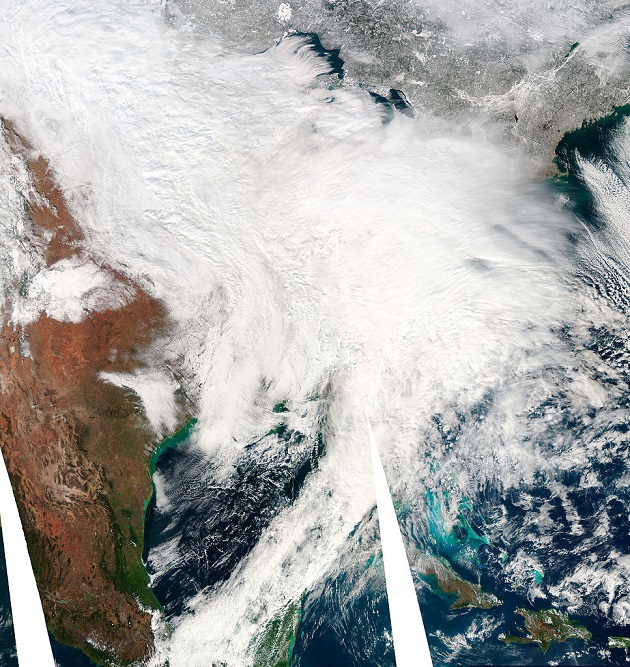

In some cases, global warming can lead to increased heavy precipitation of all kinds, and that includes snow, as anyone who lived through the recent polar vortex in the eastern US can attest. But the best conditions for snow sports depend on a snow cover that lasts through the winter, not simply a couple serious blizzards. Over the course of the season, high temperatures can burn through even the heaviest snowfall, and according to Porter Fox, that’s already happening from the Rockies to Sochi.

Fox is a veteran skier and journalist for Powder magazine who is keeping a gloved finger on the pulse of shifting slopes. He recently published a book that details how global warming is threatening the entire business model of the ski industry. It’s called Deep: The Story of Skiing and the Future of Snow. Fox joined us for today’s Inquiring Minds podcast episode, and told me that climate change could soon send snow sports crashing downhill.

You can stream our interview below (it can be found at minutes 3:30-8:30) or scroll down to read a transcript:

Porter Fox: There is going to be huge change in the ski industry in the next 10 to 20 years, and there is going to be cataclysmic change in the next 50 to 70 years. In Europe, North America, around the world, really.

Climate Desk: For skiers and snowboarders, what is that actually going to look like?

Fox: Some of the big visual indicators are we’ve lost a million square miles of spring snowpack in the last 45 years. Some other changes, in the Northern Rockies that snowpack is down 15 to 30 percent. Specifically in the US the rate of winter warming has tripled since 1970, it seems that winters are starting to warm faster than other seasons, and even high elevation areas are warming faster, and very specifically the US West is one of half a dozen hotspots that are warming faster than the national average. Every single one of those factors is bad news for the Sierras, the Rockies, the Cascades, my favorite places to ski in.

CD: Snow sports support an entire industry, including resorts, local shops and restaurants, and equipment manufacturers. How is the industry feeling this change?

Fox: The way the industry feels is that if you are not open for Christmas you’re going to lose most of your profit for that year. The Christmas holiday through New Year’s and President’s Day, those are the big moneymakers. And of course, that’s the first, that’s the earliest part of the season, and what’s happening with climate change in the Rockies and the Alps is the shoulder seasons are edging in, so the winter starts later and it ends earlier, already by a couple weeks on each end. And every year it’s getting worse and worse.

CD: What does that mean in terms of the bottom line?

Fox: It’s hitting them pretty hard. In the last 10 years, ski resorts in the US lost over a billion dollars due to low-snow years. More than 23 million people participate in winter sports activities in the States, it adds an estimated 12.2 billion dollars in economic value to the US economy. Over 200,000 jobs in the winter in the States, $7 billion in salaries, and that results in $1.4 billion in state and local taxes and $1.7 billion in federal taxes. And so now we’re not just looking at when is all the snow gone, we’re looking at when do these businesses become not viable anymore because they can’t open for Christmas. And that’s why Daniel Scott’s study of ski resorts in the Northeast, he estimated that half of the 103 ski resorts in the Northeast will close in the next 30 years.

CD: What about Sochi? How are things looking over there?

Fox: Sochi is a very interesting situation, and I didn’t study it particularly in the book but I’ve been keeping up on it ever since, and it’s a bit of a disaster right now. They stored, I believe, 16 million cubic feet of snow last season to use this season in case this happened. And they did that because they had to cancel several exhibition events last year in February, because it was too warm and there was no snow. It already happened last year. They bulldozed all this snow into giant piles, covered it with insulating tarps and basically kept it cold for this season so they can bulldoze it back onto the slopes, which looks like is exactly what they’re going to have to do. If you look at the Whistler Olympics, they had to do the same thing. They weren’t prepared for it so they lifted by helicopter tons of snow onto the slopes so they could do the skiing events. But it’s a sign, it’s a sign of things to come. It’s going to be harder and harder to find a solid snowpack as the decades pass.

CD: So. Are we looking at the end of skiing as we know it?

Fox: It’s harder to see over the course of a winter when you’re talking about power days. Powder days still come, it still happens. But when you look at the whole season-long snowpack, and how much of that snow is sitting there in the spring, and you look at trends over a decade, over 50 years, that’s what we’re talking about here. The lines on the graph are very clear. And they’re all headed down.