<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/78428166@N00/7761818952/in/photolist-cPTmmG-c8gkuJ-kMExuP-kMDvhr-kMDz5M-kMDkLn-kME51R-kMDLf2-kME84z-kMDqnB-kMEkgR-kMEcQZ-kMEnfF-kMDCK2-kME2Sc-kMDAXV-kMDQwi-kMEp3t-kMDNiv-kMDtwx-djYHAh-djYGAm-djYGy1-djYETR-djYEPK-djYGzC-djYGDf-djYESR-cRZAb5-cW1MJU-dhzKCY-dinM2v-kPa6Mo-djYES8-ddkYnE-e2Z4aF-djYFGG-ensDp1-d2jcC1-djYDWe-cVV4cd-cTmRT7-cVV48J-cTmRPm-djYE2B-djYHzf-djYFHc-djYE3x-dqVWai-dqWbBd-dqW2RW">Tony Alter</a>/Flickr

House budget committee chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) has lately rebranded himself as an advocate for the poor, albeit with his own makers-versus-takers, Ayn Randian twist. He recently issued a lengthy study of federal anti-poverty programs and over the past year and a half he has embarked on a “listening tour” to hear from low-income Americans. On Tuesday, Ryan issued the House GOP’s 2015 budget proposal, which would make major changes to two of the federal government’s primary anti-poverty programs, food stamps and Medicaid. Using as his model the supposedly successful welfare reform effort of the 1990s, Ryan envisions turning these programs into block grants that are handed over to the states to administer. But his plan to “help families in need lead lives of dignity” is likely to make matters worse for America’s neediest. Here’s why.

In 1996, Congress reengineered the federal program that provided cash assistance to the poorest families. Along with imposing stiff work requirements, Congress turned the old entitlement program, whose budget rose and fell automatically with need, into a block grant with a fixed budget. The grant was then distributed to the states, with few strings attached, under the premise that they were “laboratories of innovation” that would revolutionize the way the government helped the poor.

But as welfare reform has shown, giving states this sort of flexibility in how they spend federal money can lead to a lot of abuse that Republicans are so keen on rooting out.

According to data crunched by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, states have diverted billions of dollars of welfare block grants for uses these funds were not intended to support. In the first year of welfare reform, about 70 percent of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant went to pay for basic cash assistance for poor families. By 2012, that number had fallen to 29 percent and states were spending just 8 percent on providing transportation, job training, and other services intended to help people transition from welfare into the workforce.

The numbers are even more dismal in some individual states. In 2012, Louisiana spent 7 percent of its $261 million in TANF funds on basic assistance, down from 36 percent in 2001. Just 4 percent of the funds went to programs to help welfare recipients get back into the workforce. A mere 2 percent of the funds paid for child care, another critical component of a reform effort that was geared toward nudging women with small children into low-wage jobs.

What happened to the rest of the money? According to CBBP, 71 percent of it went to other services, including “other nonassistance,” a nebulous category used to mask payments for a hodgepodge of programs that the state didn’t want to spend its own tax revenues on.

Like Louisiana, many states have used TANF money to pay for programs that don’t necessarily help America’s lift neediest out of poverty in times of crisis or during a bad recession. TANF funds have been spent on everything from pre-K to financial aid for college students. Several states have notably tapped into TANF funds rather than raise taxes on their citizens after courts have ordered them to spend more money on the poor via other programs. Georgia, for instance, has been court-ordered to improve its child abuse and neglect system because of inadequate and dangerous conditions. Rather than raise taxes to pay for the improvements or free up funds in the state budget, Georgia now spends more than half of its federal TANF grant on foster care and related services. One of the goals of TANF, of course, is to keep children out of foster care in the first place by relieving some financial strain from their parents.

States also have used a fair amount of creative accounting to access federal TANF funds without spending much of their own money, as required by the law. When it created the TANF block grant, Congress required states to continue spending their own tax money on welfare. The legislation’s drafters wanted the states to have some skin in the game, not use the federal windfall as an excuse to repurpose their poverty spending to fill potholes or dole out tax breaks. But that’s basically what’s happened. States have taken big liberties in defining what counts as their contribution toward the TANF program.

Take New Jersey, which is under court order to provide pre-K for poor children thanks to a lawsuit that found wide disparities in funding for public schools. In 2012, the state counted as its TANF contribution more than $420 million that it was court-ordered to spend on early childhood education and full-day preschool. This saved the state from anteing up additional funds to claim federal grant money.

In 2012, Louisiana similarly counted the $46 million it spent on college financial aid as its contribution towards the welfare program. Hawaii has likewise claimed that $33 million it spent funding students at the University of Hawaii is actually anti-poverty spending.

Other states have taken this a step further, counting private funds already being spent by nonprofits such as Catholic Charities, the YMCA, or Goodwill toward their own welfare contributions. Utah, for its part, has counted volunteer services offered through one of the Mormon church’s Deseret Industry food banks as nearly half of its TANF match.

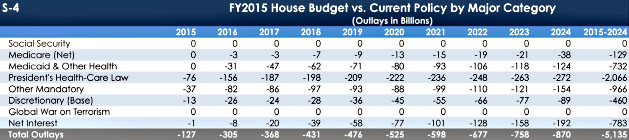

It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that the number of children and families in the US living on less than $2 a day has doubled since the welfare system was reformed. Yet under Ryan’s plan, this model would be imported into other federal anti-poverty programs that have far larger budgets than TANF, which clocks in at $16 billion a year (an amount that has remained unchanged since 1996). Given the way the block-granting system has diffused the impact of federal assistance to the extreme poor, it’s hard to see how expanding the model would help fight poverty “eye to eye, soul to soul, person to person,” as Ryan says he wants to do. In all likelihood, Ryan’s proposals would sink America’s poorest deeper into poverty while creating a spending bonanza for cash-strapped states.