<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-149675159/stock-photo-woman-looking-for-a-job.html?src=P3-VaAroFbT6m8wTCEeZpw-1-8">Gonzalo Aragon</a>/Shutterstock

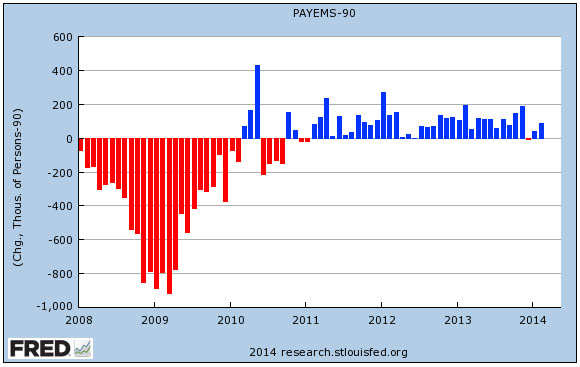

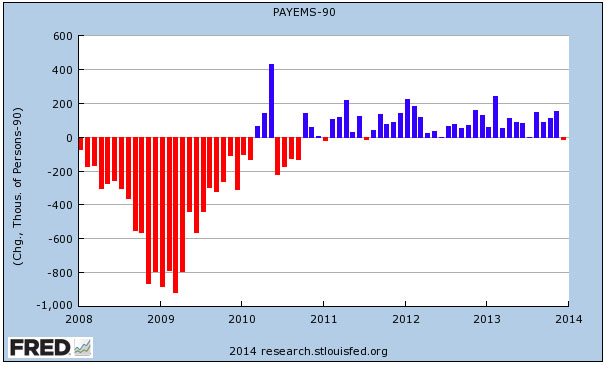

The economy added 288,000 jobs in April, according to new data released Friday by the Labor Department. The unemployment rate plummeted from 6.7 percent to 6.3 percent—which is the lowest jobless rate since President Barack Obama took office at the start of the great recession.

Economists had forecasted April jobs gains of 218,000 and an unemployment rate of 6.6 percent.

The number of unemployed people dropped by 733,000 people, and the total number of Americans who are either unemployed, have given up looking for work, or are working part-time because they can’t find full-time work fell from 12.7 percent to 12.3 percent last month. The jobs report brought more good news. Employment gains for February and March were revised upwards by a total of 36,000. Part of the healthy gain was due to warmer weather, which boosted seasonal employment.

Now for the not-so-good news. Another reason the unemployment rate fell is because April saw a decline in the workforce participation rate, which is the number of Americans who are working or looking for work. That number fell by 806,000 last month. The decrease in the labor force was partly due to the fact that Republicans refused to renew federal unemployment benefits for the long-term unemployed. Jobless Americans are required to prove they are actively searching for work in order to continue receiving unemployment insurance; once there’s less of a motivation to search, many give up looking.

The construction and retail sectors saw the largest increase in employment, with jobs gains of 32,000 and 35,000, respectively. Professional and business services added 75,000 jobs. And the economy took on a total of 15,000 government jobs.

Good or bad, you can take most of this information with a grain of salt, if you want. As Neil Irwin explained Thursday in the New York Times, businesses, journalists, and stock traders place way too much weight on the monthly jobs numbers, given the “statistical noise” in each report. In order to determine how many people are employed in the US, for example, the Labor Department conducts a huge monthly survey of 144,000 employers who employ about a third of all non-farm workers. Sampling errors are inherent in these surveys, Irwin explains, because the results are not representative of all the nation’s employers. And each monthly jobs report is released before all the survey data is in, so researchers have to fill in gaps with estimates that may later end up being wrong. “Even when the economy is moving in a clear direction,” Irwin writes, “the noise in month-to-month changes can be big enough to obscure any trend.”

If you want longer-term trends that you can bank on, here are a few. We’ve had roughly zero net job growth over the past seven years, because gains in employment have been offset by population growth. The unemployment rate is still above the historical average for this stage of an economic recovery, Annie Lowrey noted in the New York Times Friday. And the black unemployment rate is stuck at more than double the white jobless rate.