Thinkstock/mthaler

Yesterday, advocates for government transparency argued for the release of more documents that could reveal how the Federal Intelligence Act Surveillance (FISA) Court has provided oversight of the US intelligence community and confirm which telecom companies cooperated with the government. It’s the latest step in an uphill battle that’s been waged by the Electronic Frontier Foundation since 2011 for records they say may reveal disputes between the FISA court and the intelligence community, confirm the existence additional surveillance programs, and provide official acknowledgment of some essential details of known programs that have been already revealed in the media.

Under Freedom of Information Act law, the government can be compelled to release information once the existence of it has been established through authorized disclosures, like official statements and court-ordered releases. But unauthorized disclosures like leaks don’t count. That’s a problem the EFF is now grappling with. While the government has voluntarily confirmed the existence of some programs first revealed by Snowden, and the leaks themselves have revealed details that the EFF sought in its original 2011 lawsuit, leaked information can’t be used as the basis for requesting more information, even if the seeking party knows certain information and documents exist. It’s a government secrecy Catch-22.

In its original request, the EFF sought more than a thousand pages of government records. Since then, they have refocused their request on the FISA court opinions to make it easier for the court to make a decision. So far, the case has revealed a huge array of information detailing conflicts between the FISA court and the government agencies that it was charged with overseeing.

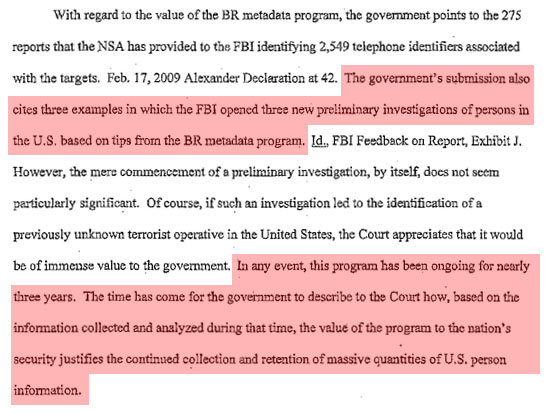

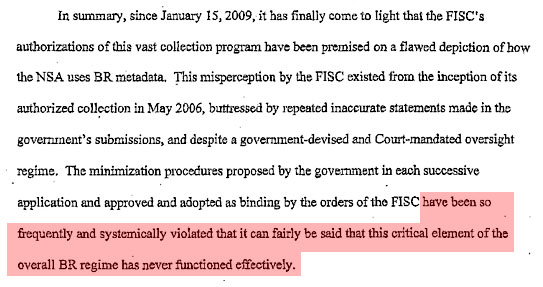

In one March 2009 opinion, released through an earlier court order in this case, the FISA court was revealed to have considered shutting down the entire NSA program because of failures to comply with its orders.

EFF is also seeking a memo from the Office of Legal Counsel to the Department of Commerce about whether or not not the Commerce Department can disclose otherwise confidential census information to intelligence agencies.

Mark Rumold, an EFF staff attorney who argued the case, said the public had a compelling need to see the remaining documents.

I think it goes without saying that the public is interested in these cases, he said of the FISA court opinions.

EFF had sued the Justice Department after its original request was denied, more than a year-and-a-half before the Snowden leaks. The revelation of certain details surrounding the mass surveillance program first reported in the Guardian and the Washington Post changed their case dramatically by confirming the details of certain programs which the government had, until then, refused to acknowledge.

Yet as Steven Bressler, the Justice Department’s lawyer,argued in court, the information revealed in those leaks couldn’t be used as the basis for additional requests.

When the Guardian and the Washington Post published these leaked documents, that didn’t declassify it, Bressler said.

Rumold described the case as incredibly unique because Snowden’s leaks and court-ordered releases made it possible to weigh the original documents the EFF sought against the governments reasons for denying their release. Snowden’s leaks revealed that much of the information which the government had denied EFF for national security reasons had no bearing on national security, he said, demonstrating that the government was acting in bad faith.

In response, Bressler said that, since the EFF was only speculating about the contents of the remaining documents, it was not in a position to determine what should or should not be classified. Moreover, he said, there is no requirement to show a threat to national security in order to be classified.

One issue argued over in court was whether the government could be compelled to reveal just the names of the telecom companies cooperating with mass surveillance. Numerous stories, based on the Snowden leaks and confidential interviews with intelligence community officials,and published in the Guardian, the Wall Street Journal and other publications, have revealed that Verizon,Sprint, and AT&T have complied with court orders to turn over phone records of their customers, but the government has not officially acknowledged their participation.

Rumold also argued that since a government official, Geoffrey Stone, a constitutional scholar at the University of Chicago who had enormous access to classified information as a member of the President’s Review Panel, had already identified these companies as participants in March, the government had no reason to refuse to acknowledge them. Stone alluded to specifics in the Daily Beast:

Under the telephone metadata program, which was created in 2006, telephone service companies like Sprint, Verizon and AT&T are required to turn over to the NSA, on an ongoing daily basis, huge quantities of telephone metadata involving the phone records of millions of Americans, none of whom are themselves suspected of anything.

In court, Bressler argued that Stones remarks didn’t verify anything. By stating companies like Verizon, Sprint, and AT&T, he left room for doubt as to which of the telecoms were actually participating, he said.

Cindy Cohn, EFF’s legal director, also present for the hearing, said she thought this was an absurd argument.

“For them to continue this pretense that nobody knows what companies are participating,” she said afterward. “It erodes peoples confidence in the government”

At the outset of the hearing, Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers said she was still wrestling with the national security implications of the documents and that she would issue a written opinion.