Child migrants at a Border Patrol facility in Brownsville, TexasEric Gay/AP

The Obama administration sent a letter to Congress on Monday asking for emergency appropriations, reportedly worth some $2 billion, to deal with the “urgent humanitarian situation” of unaccompanied child migrants in South Texas. (I’ve been reporting on the phenomenon for the past year.) But for all the talk about increasing the number of asylum officers and immigration judges, child welfare advocates are worried about a potential change in the law that could mean removing Central American kids almost immediately after they are apprehended at the border.

As Vox‘s Dara Lind explains, the president could be asking Congress to revisit the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2008. Provisions in that law exempted unaccompanied child migrants from noncontiguous countries (i.e., everywhere but Canada and Mexico) from being immediately sent back, instead funneling them to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. While the children wait for immigration judges to decide whether they qualify for asylum, ORR temporarily houses them in shelters before reunifying them with US-based family members. Here’s a handy flowchart from the Department of Homeland Security:

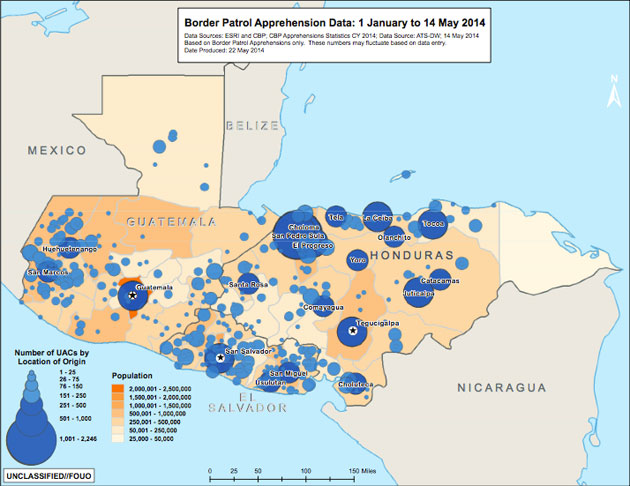

But with the recent surge of child migrants—more than 52,000 have been apprehended so far in fiscal year 2014—ORR-run shelters are at capacity, leading to an overflow of minors at Border Patrol holding facilities. On top of the violence and poverty plaguing Central America, some kids have reported hearing rumors that the US government would let them stay upon arriving—which some politicians have blamed on the fact that these children get to stay in the United States until their deportation hearings are resolved. (Right now, the average wait time for an immigration case is a year and seven months.)

So as part of the White House’s strategy to discourage the continued flow of these kids, it wants to begin treating Guatemalan, Honduran, and Salvadoran children like Mexicans, who are almost always turned back after a brief screening by a Border Patrol agent. Here are four reasons why that’s a bad idea:

1. Customs and Border Protection is a law enforcement agency, not a child welfare agency. In a 2011 report (PDF) on unaccompanied Mexican children, the public-interest law network Appleseed recommended that another Homeland Security branch, the US Customs and Immigration Service, take over the screening of these kids because “CBP officers are ill-equipped to conduct the kind of child-centric interviewing required by the TVPRA.”

Then, on June 11, the ACLU and several other groups filed a complaint against CBP on behalf of 116 unaccompanied kids, alleging physical, sexual, and verbal abuse, inhumane conditions at Border Patrol stations, as well as due process concerns. If that weren’t enough, the Border Patrol took even more flak three days later when its union, the National Border Patrol Council, tweeted the following:

While the tweet since has been deleted, it highlights the frustration of some Border Patrol agents at dealing with child migrants instead of focusing on the agency’s core mission: protecting the nation’s borders.

2. Screenings for unaccompanied Mexican kids are all over the map (if they happen at all). When an unaccompanied Mexican child is apprehended by the Border Patrol, agents are supposed to screen him within 48 hours. Specifically, they are supposed to determine three things: (1) whether the child has been the victim of trafficking; (2) whether the child has a fear of returning to Mexico; and (3) whether the child is able to voluntarily make the decision to return home. If the screening reveals that the child hasn’t been trafficked, isn’t afraid to go back, and can make the decision by himself, then he can be sent back.

In practice, says the ACLU’s Sarah Mehta, “when they’re happening, the screenings are inconsistent, but often they’re not happening.” Some agents don’t speak Spanish; in other cases, Mehta says, kids have reported not being asked any questions at all, or being told by agents that they can’t get deportation relief for whatever they experienced at home or along the way to the United States.

Also, the TVPRA states that agents must have “specialized training” to “work with unaccompanied alien children, including identifying children who are victims of severe forms of trafficking in persons, and children for whom asylum or special immigrant relief may be appropriate.” Both the Appleseed report and Mehta say there’s no indication Border Patrol agents receive such training.

3. Border Patrol facilities are terrible places to screen kids. There’s a reason why child welfare advocates talk so much about child-appropriate facilities for unaccompanied migrant kids. This Arizona placement facility, photographed on June 18, isn’t exactly what they had in mind:

“The detention environment is terrifying for most kids,” Mehta says. “It’s not an environment that kids are going to open up and talk about trafficking.” Indeed, one CBP officer told the Appleseed researchers that he doesn’t expect Mexican kids to trust agents in what he called a “police station” environment. And here’s some detail from the ACLU-led complaint filed on behalf of unaccompanied kids against CBP:

C.S. is a 17-year-old girl who was apprehended after crossing the Rio Grande. CBP detained C.S. in a hielera [a cold cell, or “freezer” in Spanish] in wet clothes that did not dry for the duration of the three and a half days she was there. The only drinking water available to C.S. came from the toilet tank in her holding cell. The bathroom was situated in plain view of all other detainees with a security camera mounted in front of it. C.S. could not sleep because the temperature was so cold, the lights were on all night, and officials frequently woke the detainees when they tried to sleep.

4. There’s too much at stake. While it’s true that many kids might not qualify for asylum or other forms of deportation relief, those who do deserve to have their claims heard by the US government. Maria Woltjen, the director of the Young Center for Immigrant Children Rights, told me last year that repatriation of unaccompanied Central American kids “is the million-dollar question.” She continued, “When kids are getting deported, there’s a phone call to find out who they’ll go back to, but the reality is our immigration officials fly them over and hand them over to some official in the country of origin.” What would that look like if summary deportation were the norm? (As I wrote earlier this month, there are limited resources available in Central America to greet deported children, let alone protect them from violence, and it is yet to be seen how much of that reported $2 billion in emergency funds will go to reintegration efforts.)

And it’s worth remembering that of the 52,000 unaccompanied kids apprehended in fiscal 2014, some 15,000 were from crumbling Honduras—including more than 2,500 from the world’s deadliest city, San Pedro Sula.

This post has been corrected. The ACLU and others filed a complaint against CBP, not a lawsuit.