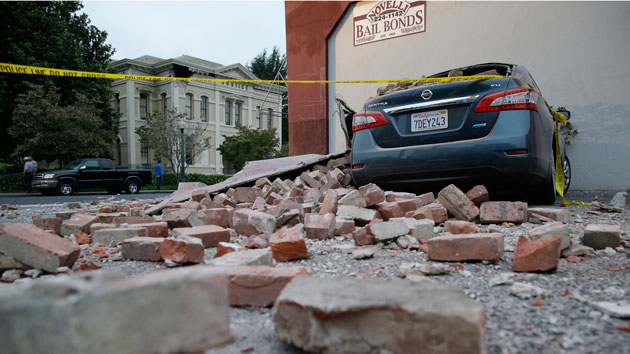

The aftermath of California's August 24 earthquake in Napa, CaliforniaEric Risberg/AP

As Bay Area residents clean their streets and homes after the biggest earthquake to hit California in 25 years rocked Napa Valley this weekend, scientists are pushing lawmakers to fund a statewide system that could warn citizens about earthquakes seconds before they hit.

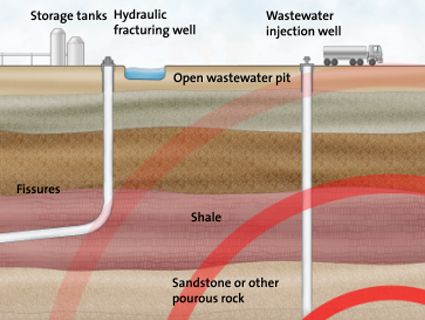

California already has a system, called ShakeAlert, that uses a network of sensors around the state to detect earthquakes just before they happen. The system—a collaboration between the University of California-Berkeley, Caltech, the US Geological Survey (USGS), and various state offices—detects a nondestructive current called a P-wave that emanates from a quake’s epicenter just before the destructive S-wave shakes the earth. ShakeAlert has successfully predicted several earthquakes, including this weekend’s Napa quake. It could be turned into a statewide warning system. But so far, the money’s not there.

“For years, seismic monitoring has been funded, essentially, on a shoestring,” says Peggy Hellweg, operations manager at UC-Berkeley’s seismological lab.

Maintaining ShakeAlert in its current state costs $15 million a year—a tiny fraction of the estimated $1 billion in damage caused by the Napa quake. Turning it into a statewide early-warning system would require installing new earthquake sensors throughout the state, building faster connections between sensors and data centers, and upgrading the data centers themselves. Since many of California’s population centers, including the Bay Area, sit on fault lines, a warning system would likely give residents little time to prepare, ranging “from a few seconds to a few tens of seconds,” depending on a person’s proximity to the earthquake’s epicenter, according to ShakeAlert’s website—not enough time to leave a large building, but perhaps enough to take cover under a desk or table. Warnings could be deployed via text messages, push notifications, or publicly funded alert systems. Setting the whole thing up could cost as much as $80 million over five years—and keeping it running would cost more than $16 million annually, according to a USGS implementation plan published earlier this year.

In September 2013, the California legislature passed a bill requiring the state’s emergency management office to work with private companies to develop an early warning system, but forbade it from pulling money from the state’s general fund. The effort got a boost last month when the House appropriations committee approved $5 million for the system, the first time Congress has allocated money for a statewide system. But the project is still short on funding.

An earthquake early-warning system would not be a unprecedented: Similar systems already exist in China, India, Italy, Romania, Taiwan, and Turkey. In Mexico City, a warning system connected to sensors 200 miles to the south gave residents two minutes’ warning before a magnitude 7.2 earthquake struck earlier this year—enough time for many to leave buildings and congregate in open areas.

More than 200 people were injured following last weekend’s Napa earthquake, 17 of them seriously, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Among those hit was a boy who was hit by debris from a falling chimney.

On Monday, the USGS said the likelihood of a “strong and possibly damaging” aftershock (magnitude 5.0 or higher) occurring within the next week was around 29 percent.