<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/gallery-50527p1.html">zimmytws</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

Imagine corporations that intentionally target low-income single mothers as ideal customers. Imagine that these same companies claim to sell tickets to the American dream—gainful employment, the chance for a middle class life. Imagine that the fine print on these tickets, once purchased, reveals them to be little more than debt contracts, profitable to the corporation’s investors, but disastrous for its customers. And imagine that these corporations receive tens of billions of dollars in taxpayer subsidies to do this dirty work. Now, know that these corporations actually exist and are universities.

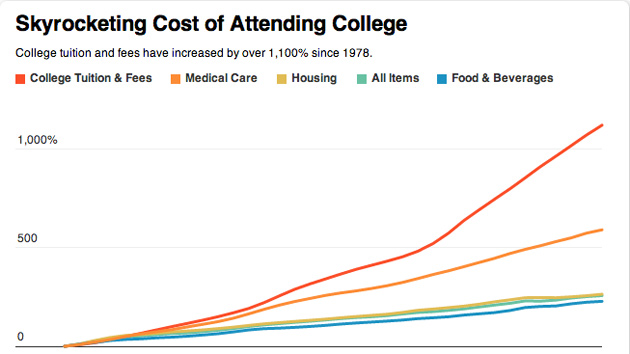

Over the last three decades, the price of a year of college has increased by more than 1,200%. In the past, American higher education has always been associated with upward mobility, but with student loan debt quadrupling between 2003 and 2013, it’s time to ask whether education alone can really move people up the class ladder. This is a question of obvious relevance for low-income students and students of color.

As Cornell professor Noliwe Rooks and journalist Kai Wright have reported, black college enrollment has increased at nearly twice the rate of white enrollment in recent years, but a disproportionate number of those African-American students end up at for-profit schools. In 2011, two of those institutions, the University of Phoenix (with physical campuses in 39 states and massive online programs) and the online-only Ashford University, produced more black graduates than any other institutes of higher education in the country. Unfortunately, a recent survey by economist Rajeev Darolia shows that for-profit graduates fare little better on the job market than job seekers with high school degrees; their diplomas, that is, are a net loss, offering essentially the same grim job prospects as if they had never gone to college, plus a lifetime debt sentence.

Much of the American public does not understand the difference between for-profit, public, and private non-profit institutions of higher learning. All three are concerned with generating revenue, but only the for-profit model exists primarily to enrich its owners. The largest of these institutions are often publicly traded, nationally franchised corporations legally beholden to maximize profit for their shareholders before maximizing education for their students. While commercial vocational programs have existed since the nineteenth century, for-profit colleges in their current form are a relatively new phenomenon that began to boom with a series of initial public offerings in the 1990s, followed quickly by deregulation of the sector as the millennium approached. Bush administration legislation then weakened government oversight of such schools, while expanding their access to federal financial aid, making the industry irresistible to Wall Street investors.

While the for-profit business model has generally served investors well, it has failed students. Retention rates are abysmal and tuitions sky-high. For-profit colleges can be up to twice as expensive as Ivy League universities, and routinely cost five or six times the price of a community college education. The Medical Assistant program at for-profit Heald College in Fresno, California, costs $22,275. A comparable program at Fresno City College costs $1,650. An associate degree in paralegal studies at Everest College in Ontario, California, costs $41,149, compared to $2,392 for the same degree at Santa Ana College, a mere 30-minute drive away.

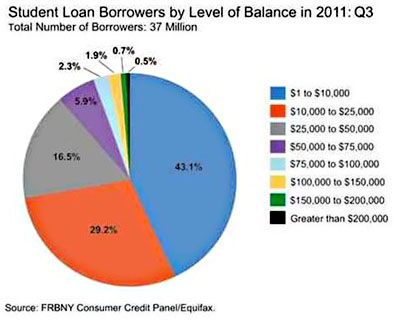

Exorbitant tuition means students, who tend to come from poor backgrounds, have to borrow from both the government and private sources, including Sallie Mae (the country’s largest originator, servicer, and collector of student loans) and banks like Chase and Wells Fargo. A whopping 96% of students who manage to graduate from for-profits leave owing money, and they typically carry twice the debt load of students from more traditional schools.

Public funds in the form of federal student loans has been called the “lifeblood” of the for-profit system, providing on average 86% of revenues. Such schools now enroll around 10% of America’s college students, but take in more than a quarter of all federal financial aid—as much as $33 billion in a single year. By some estimates it would cost less than half that amount to directly fund free higher education at all currently existing two- and four-year public colleges. In other words, for-profit schools represent not a “market solution” to increasing demand for the college experience, but the equivalent of a taxpayer-subsidized subprime education.

Pushing the Hot Button, Poking the Pain

The mantra is everywhere: a college education is the only way to climb out of poverty and create a better life. For-profit schools allow Wall Street investors and corporate executives to cash in on this faith.

Publicly traded schools have been shown to have profit margins, on average, of nearly 20%. A significant portion of these taxpayer-sourced proceeds are spent on Washington lobbyists to keep regulations weak and federal money pouring in. Meanwhile, these debt factories pay their chief executive officers $7.3 million in average yearly compensation. John Sperling, architect of the for-profit model and founder of the University of Phoenix, which serves more students than the entire University of California system or all the Ivy Leagues combined, died a billionaire in August.

Graduates of for-profit schools generally do not fare well. Indeed, they rarely find themselves in the kind of work they were promised when they enrolled, the kind of work that might enable them to repay their debts, let alone purchase the commodity-cornerstones of the American dream like a car or a home.

In the documentary “College Inc.,” produced by PBS’s investigative series Frontline, three young women recount how they enrolled in a nursing program at Everest College on the promise of $25-$35 an hour jobs on graduation. Course work, however, turned out to consist of visits to the Museum of Scientology to study “psychiatrics” and visits to a daycare center for their “pediatrics rotation.” They each paid nearly $30,000 for a 12-month program, only to find themselves unemployable because they had been taught nearly nothing about their chosen field.

In 2010, an undercover investigation by the Government Accountability Office tested 15 for-profit colleges and found that every one of them “made deceptive or otherwise questionable statements” to undercover applicants. These recruiting practices are now under increasing scrutiny from 20 state attorneys general, Senate investigators, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), amid allegations that many of these schools manipulate the job placement statistics of their graduates in the most cynical of ways.

In 2010, an undercover investigation by the Government Accountability Office tested 15 for-profit colleges and found that every one of them “made deceptive or otherwise questionable statements” to undercover applicants. These recruiting practices are now under increasing scrutiny from 20 state attorneys general, Senate investigators, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), amid allegations that many of these schools manipulate the job placement statistics of their graduates in the most cynical of ways.

The Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, an organization that offers support in health, education, employment, and community-building to new veterans, put it this way in August 2013: “Using high-pressure sales tactics and false promises, these institutions lure veterans into enrolling into expensive programs, drain their post-9/11 GI Bill education benefits, and sign up for tens of thousands of dollars in loans. The for-profits take in the money but leave the students with a substandard education, heavy student loan debt, non-transferable credits, worthless degrees, or no degrees at all.”

Even President Obama has spoken out against instances where for-profit colleges preyed upon troops with brain damage: “These Marines had injuries so severe some of them couldn’t recall what courses the recruiter had signed them up for.”

As it happens, recruiters for such schools are manipulating more than statistics. They are mining the intersections of class, race, gender, inequality, insecurity, and shame to hook students. “Create a sense of urgency. Push their hot button. Don’t let the student off the phone. Dial, dial, dial,” a director of admissions at Argosy University, which operates in 23 states and online, told his enrollment counselors in an internal email.

A training manual for recruiters at ITT Tech, another multi-state and virtual behemoth, instructed its employees to “poke the pain a bit and remind them who else is depending on them and their commitment to a better future.” It even included a “pain funnel“—that is, a visual guide to help recruiters exploit prospective students’ vulnerabilities. Pain was similarly a theme at Ashford University, where enrollment advisors were told by their superiors to “dig deep” into students’ suffering to “convince them that a college degree is going to solve all their problems.”

An internal document from Corinthian Colleges, Inc. (owner of Everest, Heald, and Wyotech colleges) specified that its target demographic is “isolated,” “impatient” individuals with “low self-esteem.” They should have “few people in their lives who care about them and be stuck in their lives, unable to imagine a future or plan well.”

These recruiting strategies are as well funded as they are abhorrent. When an institution of higher learning is driven primarily by the needs of its shareholders, not its students, the drive to get “asses in classes” guarantees that marketing budgets will dwarf whatever is spent on faculty and instruction. According to David Halperin, author of Stealing America’s Future: How For-Profit Colleges Scam Taxpayers and Ruin Student’s Lives, “The University of Phoenix has spent as much as $600 million a year on advertising; it has regularly been Google’s largest advertiser, spending $200,000 a day.”&

At some schools, the money put into the actual education of a single student has been as low as $700 per year. The Senate’s Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee revealed that 30 of the for-profit industry’s biggest players spent $4.2 billion—or 22.7% of their revenue—on recruiting and marketing in 2010.

Subprime Schools, Swindled Students

In profit paradise, there are nonetheless signs of trouble. Corinthian College Inc., for instance, is under investigation by several state and federal agencies for falsifying job-placement rates and lying to students in marketing materials. In June, the Department of Education discovered that the company was on the verge of collapse and began supervising a search for buyers for its more than 100 campuses and online operations. In this “unwinding process,” some Corinthian campuses have already shut down. To make matters worse, this month the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announced a $500 million lawsuit accusing Corinthian of running a “predatory lending scheme.”

As the failure of Corinthian unfolds, those who understood it to be a school—namely, its students—have been left in the lurch. Are their hard-earned degrees and credits worthless? Should those who are enrolled stay put and hope for the storm to pass or jump ship to another institution? Social media reverberate with anxious questions.

Nathan Hornes started the Facebook group “Everest Avengers,” a forum where students who feel confused and betrayed can share information and organize. A 2014 graduate of Everest College’s Ontario, California, branch, Nathan graduated with a 3.9 GPA, a degree in Business Management, and $65,000 in debt. Unable to find the gainful employment Everest promised him, he currently works two fast-food restaurant jobs. Nathan’s dreams of starting a record label and a music camp for inner city kids will be deferred even further into some distant future when his debts come due: a six-month grace period expires in October and Nathan will owe $380 each month on Federal loans alone. “Do I want to pay bills or my loans?” he asks. Corinthian has already threatened to sue him if he fails to make payments.

Asked to explain Corinthian’s financial troubles, Trace Urdan, a market analyst for Wells Fargo Bank, Corinthian’s biggest equity investor, argued that the school attracts “subprime students” who “can be expected—as a group—to repay at levels far lower than most student loans.” And yet, as Corinthian’s financial woes mounted, the corporation stopped paying rent at its Los Angeles campuses and couldn’t pay its own substantial debts to lenders, including Bank of America, from whom it sought a debt waiver.

That Corinthian can request debt waivers from its lenders should give us pause. Who, one might ask, is the proper beneficiary of a debt waiver in this case? No such favors will be done for Nathan Hornes or other former Corinthian students, though they have effectively been led into a debt trap with an expert package of misrepresentations, emotional manipulation, and possibly fraud.

From Bad Apples to a Better System, or Everest Avenged

As is always the case with corporate scandals, Corinthian is now being described as a “bad apple” among for-profits, not evidence of a rotten orchard. The fact is that for-profits like Corinthian exemplify all the contradictions of the free-market model that reformers present as the only solution to the current crisis in higher education: not only are these schools 90% dependent on taxpayer money, but tenure doesn’t exist, there are no faculty unions, most courses are offered online with low overhead costs, and students are treated as “customers.”

It’s also worth remembering that at “public” universities, it is now nearly impossible for working class or even middle class students to graduate without debt. This sad state of affairs—so the common version of the story goes—is the consequence of economic hard-times, which require belt tightening and budget cuts. And so it has come to pass that strapped community colleges are now turning away would-be enrollees who wind up in the embrace of for-profits that proceed to squeeze every penny they can from them and the public purse as well. (All the while, of course, this same tale provides for-profits with a cover: they are offering a public service to a marginalized and needy population no one else will touch.)

The standard narrative that, in the face of shrinking tax revenues, public universities must relentlessly raise tuition rates turns out, however, to be full of holes. As political theorist Robert Meister points out, this version of the story ignores the complicity of university leaders in the process. Many of them were never passive victims of privatization; instead, they saw tuition, not taxpayer funding, as the superior and preferred form of revenue growth.

Beginning in the 1990s, universities, public and private, began working ever more closely with Wall Street, which meant using tuition payments not just as direct revenue but also as collateral for debt-financing. Consider the venerable but beleaguered University of California system: a 2012 report out of its Berkeley branch, “Swapping Our Futures,” shows that the whole system was losing $750,000 each month on interest-rate swaps—a financial product that promised lower borrowing costs, but ended up draining the U.C. system of already-scarce resources.

In the last decade, its swap agreements have cost it over $55 million and could, in the end, add up to a loss of $200 million. Financiers, as the university’s creditors, are promised ever-increasing tuition as the collateral on loans, forcing public schools to aggressively recruit ever more out-of-state students, who pay higher tuitions, and to raise the in-state tuition relentlessly as well, simply to meet debt burdens and keep credit ratings high.

Instead of being the social and economic leveler many believe it to be, American higher education in the twenty-first century too often compounds the problem of inequality through debt-servitude. Referring to student debt, which has by now reached $1.2 trillion, Meister suggests, “Add up the lifetime debt service that former students will pay on $1 trillion, over and above the principal they borrow, and you could run a very good public university system for what we are paying capital markets to fund an ever-worsening one.”

You Are Not a Loan

The big problem of how we finance education won’t be solved overnight. But one group is attempting to provide both immediate aid to students like Nathan Hornes and a vision for rethinking debt as a systemic issue. On September 17th, the Rolling Jubilee, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, announced the abolition of a portfolio of debt worth nearly $4 million originating from for-profit Everest College. This granted nearly 3,000 former students no-strings-attached debt relief.

The authors of this article have both been part of this effort. To date, the Rolling Jubilee has abolished nearly $20 million dollars of medical and educational debt by taking advantage of a little-known trade secret: debt is often sold to debt collectors for mere pennies on the dollar. A medical bill that was originally $1,000 might sell to a debt collector for 4% of its sticker price, or $40. This allowed the Rolling Jubilee project to make a multi-million dollar impact with a budget of approximately $700,000 raised in large part through small individual donations.

The point of the Rolling Jubilee is simple enough: we believe people shouldn’t have to go into debt for basic needs. For the last four decades, easy access to credit has masked stagnating wages and crumbling social services, forcing many Americans to debt-finance necessities like college, health care, and housing, while the creditor class has reaped enormous rewards. But while we mean the Jubilee’s acts to be significant, we know it is not a sustainable solution to the problem at hand. There is no way to buy and abolish all the odious debt sloshing around our economy, nor would we want to. Given the way our economy is structured, people would start slipping into the red again the minute their debts were wiped out.

The Rolling Jubilee instead raises a question: If a ragtag group of activists can find a way to provide immediate relief to even a few thousand defrauded students, why can’t the government?

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s lawsuit against Corinthian Colleges, Inc. is a good first step, but it only applies to specific private loans originating after 2011, and it will likely take years to play out. Until it’s resolved, students are still technically on the hook and many will be harassed by unscrupulous debt collectors attempting to extract money from them while they still can. In the meantime, the Department of Education (DOE)—which has far greater purview than the CFPB—is effectively acting as a debt collector for a predatory lender, instead of using its discretionary power to help students. Why didn’t the DOE simply let Corinthian go bankrupt, as often happens to private institutions, and so let the students’ debts become dischargeable?

Such debt discharge is well within the DOE’s statutory powers. When a school under its jurisdiction has broken state laws or committed fraud it is, in fact, mandated to offer debt discharge to students. Yet in Corinthian’s opaque, unaccountable unwinding process, the Department of Education appears to be focused on keeping as many of these predatory “schools” open as possible.

No less troubling, the DOE actually stands to profit off Corinthian’s debt payments, as it does from all federally secured educational loans, regardless of the school they are associated with. Senator Elizabeth Warren has already sounded the alarm about the department’s conflict of interest when it comes to student debt, citing an estimate that the government stands to rake in up to $51 billion dollars in a single year on student loans. As Warren points out, it’s “obscene” for the government to treat education as a profit center.

Can there be any doubt that funds reaped from the repayment of federally backed loans by Corinthian students are especially ill-gotten gains? Nathan Hornes and his fellow students should be the beneficiaries of debt relief, not further dispossession.

Unless people agitate, no reprieve will be offered. Instead there may be slaps on the wrist for a few for-profit “bad apples,” with policymakers presenting possible small reductions in interest rates or income-based payments for student borrowers as major breakthroughs.

We need to think bigger. There is an old banking adage: if you owe the bank $1,000, the bank owns you; if you owe the bank $1 million, you own the bank. Individually, student debt is an incapacitating burden. But as Nathan and others are discovering, as a premise for collective action, it can offer a new kind of leverage. Debt collectives, effectively debtors’ unions, may be the next stage of anti-austerity organizing. Collective action offers many possibilities for building power against creditors through collective bargaining, including the power to threaten a debt strike. Where for-profits prey on people’s vulnerability, isolation, and shame, debt collectives would nurture feelings of strength, solidarity, and outrage.

Those who profit from education fear such a transformation, and understandably so. “We ask students to make payments while in school to help them develop the discipline and practice of repaying their federal and other loan obligations,” a Corinthian Colleges spokesman said in response to the news of CFPB’s lawsuit.

It’s absurd: a single mother working two jobs and attending online classes to better her life is discipline personified, even if she can’t always pay her loans on time. The executives and investors living large off her financial aid are the ones who need to be taught a lesson. Perhaps we should collectively demand that as part of their punishment these predators take a course in self-discipline taught by their former students.

Hannah Appel is a mother, activist, and assistant professor of anthropology at UCLA. Her work looks at the everyday life of capitalism and the economic imagination. She has been active with Occupy Wall Street since 2011.

Astra Taylor is a writer, documentary filmmaker (including Zizek! and Examined Life), and activist. Her book, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (Metropolitan Books), was published in April. She helped launch the Occupy offshoot Strike Debt and its Rolling Jubilee campaign. To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.