The photo of the LSU keg stand with @SenLandrieu you’ve all been waiting for. #RollCallontheRoad #LASen pic.twitter.com/wk6M8Rx1Lq

— Bill Clark (@clarkshadows) September 21, 2014

It’s game day in Baton Rouge, and the bro in the purple shirt wants Mary Landrieu’s help doing a keg stand.

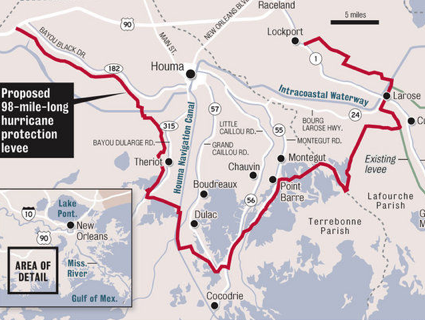

Landrieu, elected three times by the narrowest of margins, is once again locked in a tight reelection campaign, this time against GOP Rep. Bill Cassidy. With six weeks until Election Day, every moment counts. She spent her Saturday morning at a beach near Lake Charles, in the state’s southwest corner, taking part in a cleanup effort cosponsored by Citgo, the Venezuelan oil company, pegged to the anniversary of Hurricane Rita. As a member of the president’s party in a state where the president is deeply unpopular, this event neatly encapsulates Landrieu’s strategy: Keep it local. She’ll fight for coastal restoration, but she’ll also fight for the oil and gas industry, and with her seniority and connections, she’ll cut deals to help out both.

The other part of her pitch is that she is an independent-minded daughter of Louisiana who is in touch with the needs and traditions of her constituents. Over the last month or so, that part of her messaging has taken a hit. First, the Washington Post reported that Landrieu listed her primary residence as her parents’ New Orleans home but spent most of her time in Washington, DC. Seeing an opportunity, a one-time Republican challenger filed a lawsuit to have her taken off the ballot (that suit was thrown out). Thus, here we are on the edge of the LSU’s quad, four hours before the Tigers kick off against the Mississippi State Bulldogs, contemplating keg stands.

I had caught up to Landrieu a few minutes earlier in a more subdued environment, at a tent filled with campaign volunteers manned by her younger brother, Mark, a real estate broker. Landrieu has eight siblings, all of whom have names that start with the letter “M,” taking after their father, Moon, who was formerly known as Maurice. The plan is to fan out across campus—which on game days draws nearly 100,000 people—and hand out stickers that say “I’m with Mary.”

Landrieu, also wearing one of those stickers, introduces herself to strangers with a straightforward, “Hi, I’m Mary.” There are plenty of supporters—longtime friends, fellow members of the Delta Gamma sorority, folks who recognize her from television and want a selfie. There are also plenty of drunk kids; visitors from Mississippi; and the politically oblivious—who smile as if to say, “Of course you’re Mary,” and return to their conversations.

Landrieu asks a volunteer whether we should head toward the quad. “The quad’s a little crazy,” the volunteer warns. “I mean, there are some wild and crazy people.”

A wise man. As we forge deeper and deeper into the maze of solo cups and cornhole, a group of bros, head to toe in purple and gold, recognize Landrieu and take up the chant LSU fans reserve for rivals. “Tiger bait! Tiger bait!”

She drifts toward friendlier territory. “Hey Mary! Mary, go do a keg stand!” says a student in a gold polo shirt. A volunteer offers him a sticker, which he declines. “Tell her I don’t support her!” he tells the volunteer. I ask him if he’d support her if she did a keg stand, and he says, “Fuck no!” Then he grabs my arm and shouts at me. “Hey! Write it down: ‘SNT! Saturday! Night! Tailgate!'”

Landrieu has by this point been swallowed by the crowd. She is surrounded by raucous fans on three sides and a pile of pizza boxes on the other. The pressure mounts, again, for a keg stand. A chant begins. “Mary! Mary! Mary!” The senior United States senator from the great state of Louisiana picks up the nozzle of the keg, and…does not do a keg stand. But she does help a purple-shirted bro do one. So, points for that.

Perhaps sensing the expedition to the quad veering into Animal House terrain, Landrieu grabs a volunteer, who in turn grabs me, to bear witness to something more genteel. She puts her arms around three young students. “These are my sorority sisters, and we are trading stickers,” Landrieu says. “I’m gonna get a Delta Gamma, and they’re getting an ‘I’m with Mary.'”

“My first keg stand,” Landrieu says, as we walk away. “He wanted me to do it, but I said absolutely not—at least not in front of the national press.” What if it would’ve won her some votes? “That’s all right—I’m not that desperate.”

Then again, running against the cookie-cutter Cassidy, whose ads attacking Landrieu basically consist of him saying “Barack Obama” over and over again (a pretty good strategy, it turns out), maybe the quad isn’t the worst place for Landrieu. No one’s going to confuse her with Huey Long reciting “Evangeline” on the stump, but it’s good to look human. Landrieu is a Democratic politician from the South, which is to say she tailgates for a living. She makes a point, she tells me, to go at least once a year to every major college football program in the state—Lafayette and Monroe and Tech and so on—but is by nature a Tigers fan. I ask her if the Tigers players who take the field against Mississippi State should, as many have suggested, be paid for their labor.

“Oh, I am not gonna talk to you about any of that right now—I do not have time for that today, mister,” she says, pounding me on the arm. “We are here to have fun!”

But not for too much longer. She shakes a few more hands, says goodbye to her brother, strolls past one last crowd of chanting bros throwing cans of beer high into the air, and hops in a car back to New Orleans.

Ultimately, though, the action on the field may do as much to determine the winner of the Senate race than any meet and greet. If, as looks exceedingly likely, neither Landrieu nor Cassidy reach 50 percent on Election Day, they’ll meet in a runoff on December 6th. Get-out-the-vote efforts might face an obstacle that day—that’s the Southeastern Conference championship game.