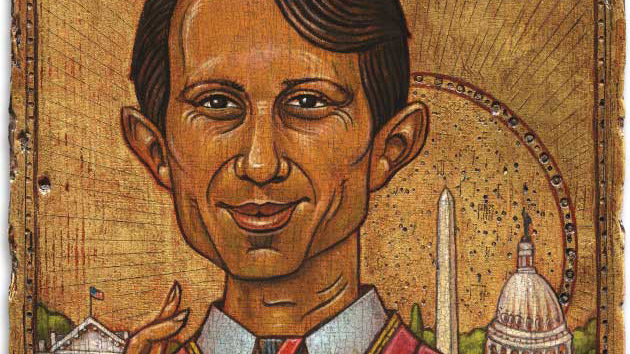

Former Gov. Edwin Edwards (D-La.)Travis Spradling/Associated Press

Eight weeks before election day, Democrats’ best hope in Louisiana’s sixth congressional district is at the VIP room of an all-you-can-eat restaurant in Denham Springs, talking about his baggage.

“When I was here in 1971, I was running for governor and nobody knew me, and that was not too good,” Edwin Edwards explains to the local Kiwanis Club, in his French-inflected Acadia Parish cadence. “Now I’m running for Congress and everybody knows me and that’s not good.”

After eight years in federal prison for corruption and one-short-lived reality show, the 87-year-old Edwards is back. The former four-term governor and four-term congressman known for his womanizing and gambling (and one-liners about both) is gunning for the South Louisiana House seat being vacated by GOP Rep. Bill Cassidy, who is running for Senate.

But Edwards isn’t even the strangest candidate in the race. The wide-open field also features 10 Republicans, four of whom could win: a self-proclaimed Sarah Palin disciple; a 28-year-old techie; an unabashed Koch brothers supporter; and an outspoken state senator.

As the only Democrat of note in a 13-person field, Edwards should get enough votes to move on to the December 6th run-off (if, as expected, no one in the race captures 50 percent of the vote). But he is not going to win a runoff in the the sixth district, which stretches from Baton Rouge and its suburbs south along Bayou LaFourche and gave Mitt Romney 66 percent of the vote in 2012. Barring a dead-girl live-boy situation (to borrow one of the governor’s most famous quips), one of those four Republicans is certain to be in Congress next year.

I met two of the contenders at a candidate forum in Gonzales, a blue-collar town on I-10. The hope of the GOP’s netroots is Baton Rouge-based tech entrepreneur Paul Dietzel, who at 28 is 59 years younger than Edwards and the youngest Republican in a major race in 2014. Dietzel projects an air of Alex P. Keaton precociousness and makes it a point of reciting from memory how long he has been in this race (it is 545 days as of this writing). Until last January, he was legally known as Stephen Paul Dietzel, but he has since had his name shortened to Paul—just like his grandfather, a beloved LSU football coach. (Dietzel has said the switch was done to make legal paperwork easier, although it doesn’t hurt with name recognition.)

Dietzel’s great passion—other than repealing the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill and dramatically shrinking the Department of Education—is using his technological know-how to help save America. But this isn’t the standard pitch about internet freedom and start-up culture. “Though Congress may not understand the technology,” he said in his opening remarks in Gonzales, “the threat of a cyber-attack or electro magnetic pulse is real.”

This wasn’t what the crowd was expecting, but Dietzel had pledged an unorthodox campaign, free of consultants. He went on, explaining how a foreign country or terrorist organization could send the United States back to the 18th century by detonating a thermo-nuclear device in the atmosphere that would fry the grid. “Last year the North Koreans actually practiced some EMP attacks on us,” he said. “It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when, and we have to be ready. Unfortunately we’re not. Engineers gave our electrical grid a D-plus—that’s not even good by Common Core standards!”

Dietzel is not in the cybersecurity business. After he left business school at Pepperdine, he launched a company called Anedot (an anagram for “donate”) that specializes in helping non-profits raise money during live events. Anedot was used at the Iowa Straw Poll in 2011, which is where Dietzel was introduced to Mike Huckabee, who has endorsed his campaign. RedState founder Erick Erickson and former presidential candidate Herman Cain have also backed Dietzel. (Cain’s former personal assistant is Dietzel’s campaign manager.) Speaking mostly to an audience of senior citizens, he happily played up his campaign’s youngster bent—at last count Dietzel had a small army of 200 interns working for him.

Sitting three seats over from Dietzel at the Gonzalez La Quinta, Garret Graves, the bowl-cutted choice of the Chamber of Commerce crowd, offered an argument rarely seen in congressional campaigns—you should vote for him because he’s a Washington insider. Once a staffer for former Rep. Billy Tauzin (R) and former Sen. John Breaux (D)—centrist lawmakers with energy-industry connections who are now two of Washington’s most powerful lobbyists—Graves returned to Louisiana to work as Gov. Bobby Jindal’s coastal restoration guru in 2008. His task: devise and implement a $50 billion plan to save the state’s coast and shore up its storm defenses.

The 6th district, which sits mostly at sea level, is especially threatened by climate change and erosion. But Graves’ tenure ended in controversy when he helped squash a lawsuit filed by a state-sanctioned flood board that was attempting to collect damages from nearly 100 oil and gas companies. Graves sells himself by vowing that he will stand up for the oil and gas and petrochemical industry, and use his experience and connections to get things done. “That’s why Mary Matalin, that’s why the Koch brothers, Koch Industries, are supporting my campaign,” he said in his closing argument at the forum. (This is a reference to the $5,000 donation Graves received from KochPAC, the company’s political action committee.)

Having worked in some capacity with most of the biggest businesses in South Louisiana—and gone to bat for the biggest industry in the district—Graves has raised almost twice as much campaign money as anyone else in the race. In a contest where a Republican could advance to the runoff with as little as 20 percent of the vote, his ability to saturate the district with television ads in the final weeks provides him with an important advantage.

After he was done talking in Gonzalez, I asked Graves about his Koch brothers shout-out, an unusual boast in a campaign in which Democrats have spent millions of dollars tarring Republicans as Koch puppets. “Over the years one of the biggest frustrations people have with Congress is the complete dysfunction,” he said. “I actually believe in what Koch Industries—the Koch brothers have been pushing in regard to reducing the size of the federal government.”

But where the Kochs have channeled millions of dollars to groups that have muddied the science of climate change, Graves acknowledges the impact of rising sea levels on the state. Although he said “the climate’s always changed” and views wetlands protection and management as more serious challenges, he noted that Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority relied on up-to-date climate science for its planning. “Our master plan looked at the measured rise of seas that they’ve experienced over recent years,” Graves said. “We’d be idiotic to not factor that into future change. So it’s in the Master Plan.”

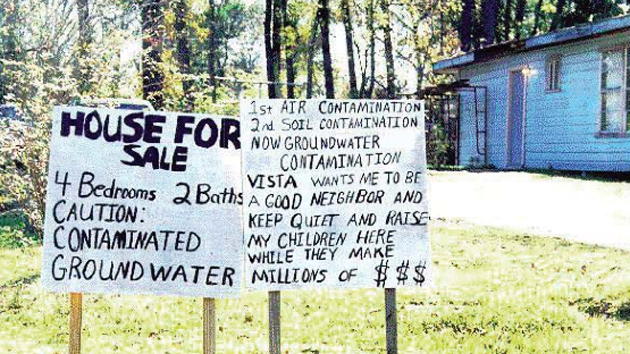

Notably absent from the forum in Gonzalez was state Rep. Lenar Whitney, a dance instructor from Houma who calls herself the “Palin of the South” and who has received the endorsement of the state’s largest tea party group. I went to Houma the next day in search of her campaign office and discovered that Whitney was running the entire operation out of her house, a few hundred yards from Bayou LaFourche. “It’s a virtual campaign,” a helpful volunteer told me. In lieu of yard signs, Whitney’s campaign is handing out life-size cardboard cutouts of the candidate, arms folded triumphantly.*

Whitney has mostly stopped giving interviews after a trip to Washington, DC, in July resulted in the Cook Political Report‘s Dave Wasserman, who interviews virtually every serious congressional candidate in the course of his duties, calling her “the most frightening candidate I’ve met in seven years.” (Whitney fled Wasserman’s office after refusing to say whether President Barack Obama was born in the United States.)

Whitney has called for requiring “welfare recipients” to provide a birth certificate before receiving government money (to prevent undocumented residents from collecting benefits) and wants mandatory-minimum prison sentences for employers who hire undocumented workers. “If we can secure the border between South Korea and North Korea,” Whitley asks in one campaign ad, “why can’t we do the same between Mexico and Texas?” (Maybe because the DMZ is filled with landmines.)

Houma is 10 feet above sea level, but Whitney says climate change is “perhaps the greatest deception in the history of mankind” and must be rejected because “the conspiracy of global warming has had a devastating effect on the American dream.”

Whitney is a long-shot, but local political handicappers say that because she is the only candidate in the race from the southern arm of the district (Houma is just outside the district’s limits), she just might be able to squeak out an upset if Baton Rouge candidates split the vote there.

Then there is state Sen. Dan Claitor. He’s the Republican in the race with the best record of impressing voters in the district, having been elected twice to the Baton Rouge state Senate seat Cassidy once held. As Louisiana Republicans have soured on Gov. Bobby Jindal, who pushed an unpopular tax-reform proposal and has flip-flopped on the Common Core education standards that conservatives have rallied against, Claitor has positioned himself as the face of the GOP opposition.

But Claitor also ticked off some Republicans for his criticism of Family Research Council president Tony Perkins, a nationally prominent social conservative who had flirted with running for the seat. “I don’t want Louisiana to become the focus of the national media because we have extremists running for a particular office,” Claitor told the New Orleans Times-Picayune in December.

Perkins has since endorsed Whitney, the dance instructor. Claitor, perhaps sensing the heat, has had a change of heart. “I’ve come to understand their situation better than I have in the past,” Claitor said after a meeting with a Republican women’s group in Thibodaux. “I frankly didn’t know the—what was the name of his group there in Washington, DC?—whatever they are, Family Research Council, that’s a national organization, I’m not a national politician.” He praised Perkins for his work on behalf of Miriam Ibrahim, a Sudanese Christian whom American evangelicals had worked to free from prison.

With most of the polling in-state focusing on the back-and-forth Senate race, there’s no consensus on who the Republican entry in the runoff will be. But whoever emerges as the second candidate in the head-to-head race is in good shape. “I don’t think Edwards could beat anybody, unless the person he’s running against has committed a worse crime than him,” says Bob Mann, a former aide to Democratic ex-Gov. Kathleen Blanco.

Edwards, one of a handful of Southern congressmen to support extending the Voting Rights Acts during his stint in Congress, always won black voters by huge margins. But his new district is significantly whiter than the rest of a state that’s become increasingly polarized. No voter under the age of 41 has ever seen Edwards on the ballot; many of the people who ever voted for him are dead; and, also, he went to prison. “Even in his best election, he probably only got about 50 percent of the white vote,” Mann says. “I don’t think that’s possible for any Democrat now.”

But Edwards doggedly persists, running through his hits like an aging rock star. At the Kiwanis Club in Denham Springs, the Baton Rouge suburb where he moved with his wife Trina, and infant son, Eli, after getting out of prison three years ago (an A&E reality show featuring the family was widely panned), he justifies his run for office as one last shot at his life’s calling. “‘You’re 87 years old and retired, why don’t you just sit home and do what you feel like doing?'” he says, recalling a recent conversation with a woman who’d suggested he hang it up. His response: “That’s what I feel like doing, lady!”

Edwards walks the group through his campaign platform. It focuses on a series of infrastructure improvements to the Baton Rouge area. He’ll bring in high-speed rail, build a new elevated expressway through the capital, keep the Mississippi River open for business, and restore the coast. (Edwards supported the lawsuit Graves helped extinguish.) With a platform like that, it sounds like he’d rather be running for governor—which he would, except as a felon he’s prohibited by state law from doing so for another seven years.

“I don’t know what the devil is happening in the Mideast,” he says, and he isn’t sure if he’d have voted for the Affordable Care Act. (But he thinks Louisiana should take the money for Medicaid expansion.) Finally, he addresses the subject on everyone’s mind. Whatever his personal flaws, Edwards tells the club, he never stole money from the state. This defense is a non sequitur; he was convicted of accepting and soliciting bribes, not looting the treasury.

“Find a good reason,” he says. “I don’t call my daughter up, I wear suits that don’t match, I have—some people say I have a Cajun accent. Find some good reason to vote against me. That bothers me, because I’d like your vote, but you know what? I’d rather have your respect.”

Then Edwards partakes in some of the flesh-pressing that was his bread-and-butter in the glory days. When the parish coroner and his wife come up to say hello, he compliments the woman on her dimples, briefly expresses interest in the job of coroner, and returns once more to the dimples. “I was gonna say,” Edwards tells his supporter, “you and I have something in common—we both like younger chicks!” Then he goes gravely serious. “I have a question: Do you think I should have got into it about stealing the money?” The coroner reassures him: “Whatever you did came across as genuine,” he says. Edwards looks relieved.

We chat about the race for a little while, and as I go to leave, I inquire about the blue band on his wrist. Edwards takes it off to show me his name written on the side, then hands it over. “Go ahead,” he says. “You’re not the first reporter who took something from me for free,” he says. “Except what they took was valuable.”

“I’m just kidding, man,” he adds. Maybe the old man’s still got it.

Correction: An earlier version of this article originally misquoted Whitney’s description of herself.