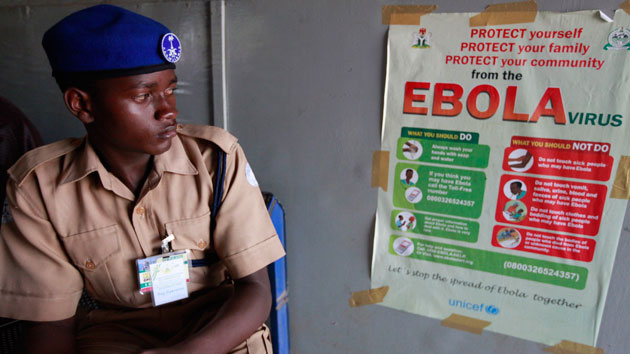

An Ebola warning at the Murtala Muhammed International Airport in LagosSunday Alamba/AP

Update, October 20, 11 a.m EDT: Forty-two days after Nigeria’s last infection, the World Health Organization has officially declared the country “free of Ebola virus transmission.”

“This is a spectacular success story that shows that Ebola can be contained,” the WHO said in a statement, adding that Nigeria’s success could be a lesson for other countries in the world experiencing an outbreak. “Many wealthy countries, with outstanding health systems, may have something to learn as well,” it added.

Ebola first arrived in Lagos, Nigeria—one of the largest cities in the world—on July 20. Global health officials feared the worst, warning that the disease could wreak untold havoc in the country.

But it hasn’t turned out that way. To date, Nigeria has reported only 20 confirmed or probable Ebola cases in a nation of 174 million people. Equally remarkable, there have only been eight deaths—about half the fatality rate experienced by other countries involved in the current outbreak. In fact, Nigeria could be declared Ebola-free as early as October 12. (That date would be 42 days after the last case was diagnosed, or double the maximum amount of time needed for the disease to incubate in a human body—the standard used by global health authorities.)

Nigeria’s success in stopping the outbreak could have implications for other countries, including the United States. That’s why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) dispatched a team to the country this week to learn what went right.

So how did local and international health authorities curb Ebola in Nigeria while infections have continued to rise dramatically in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea?

Early identification: By the time Patrick Sawyer, the Liberian American who brought Ebola to Nigeria, arrived in Lagos on July 20, Nigerian officials were on the lookout for the disease. Sawyer was “acutely ill” when he landed at the airport, according to a CDC report. He went directly to a hospital, where doctors diagnosed him with malaria. But when anti-malaria treatments failed, doctors immediately began treating his symptoms as if they were Ebola. Sawyer was isolated in the hospital while doctors notified local officials of a possible case of Ebola and rushed blood samples to a local university for testing. (Sawyer died on July 25.)

Coordinating a response: Just three days after Sawyer arrived in Lagos, Nigerian officials—working with the World Health Organization, Doctors Without Borders, UNICEF, and the CDC—established an operations center to respond to the outbreak. In its report, the CDC praised the collective effort. “Immediately, the [Emergency response center] developed a functional staff rhythm that facilitated information sharing, team accountability, and resource mobilization while attempting to minimize the distraction of teams from their highest priorities,” the agency wrote. Having all the relevant government and international authorities in one place helped streamline decision-making and ensured a “rapid, effective, and coordinated” response, according to the CDC.

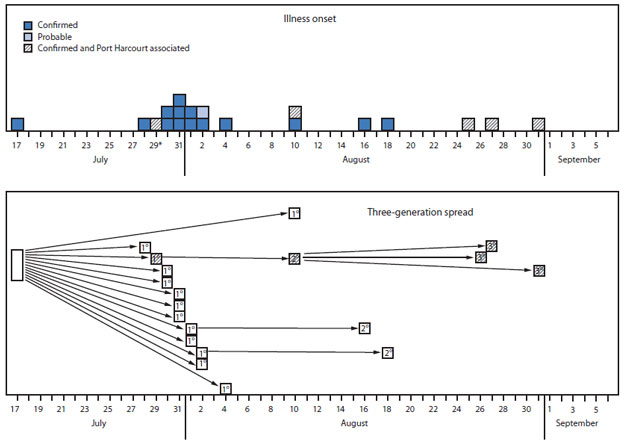

Tracing contacts—fast: With an emergency response team in place, the next step was to find anyone else who might have the virus. Over the course of the outbreak, a team that included more than a dozen Nigerian, WHO, and CDC epidemiologists and 150 “tracers” descended on Lagos and Port Harcourt—the city to which an infected doctor involved in Sawyer’s treatment had fled—searching for anyone who had contact with an Ebola victim. Once a contact was identified, the teams interviewed people in a radius of up to two kilometers around the person’s house. By September 24, according to the CDC, tracers had covered roughly 26,000 houses and had conducted 18,500 face-to-face visits throughout Nigeria looking for symptoms. In all, the team identified 894 people who had been in contact with Ebola patients. The teams monitored these contacts for symptoms, and isolated suspected cases. The aggressive tactics worked. As the chart below shows, most Ebola patients in Nigeria didn’t infect anyone else.

“The success we have had is a testimony to what we can achieve as people if we set aside our differences and work together,” said Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan during an address in late August, toward the end of his country’s outbreak. “We will continue to monitor the situation, and we will also support other affected African countries as much as we can because we cannot be completely safe from the virus as long as it continues to ravage some countries in our subregion and continent.”