Chicago Maroon/<a href="https://berniesanders.com/">Bernie Sanders</a>

Editor’s note: Sen. Bernie Sanders jumped into the crowded 2020 race. This story was published during his first presidential bid. Click here for more Sanders stories from Mother Jones’ archives.

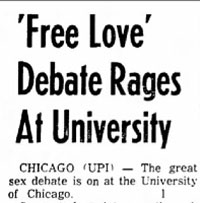

When Bernie Sanders was a student activist at University of Chicago in the 1960s, he was a leader of the local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality and helped to organize a protest of the school’s racist housing policies. But the radical action he mounted that received nationwide attention was of a different nature: In 1963, as a junior, he waged a crusade for sexual freedom, assailing the school’s leaders for forcing their puritan views on undergraduates—and ruining their students’ sex lives.

In doing so, Sanders made national news. This crusade was emblematic of the way Sanders conducted himself in Hyde Park and throughout his political career—firm in his beliefs, fiery in his rhetoric, and unafraid of confrontation.

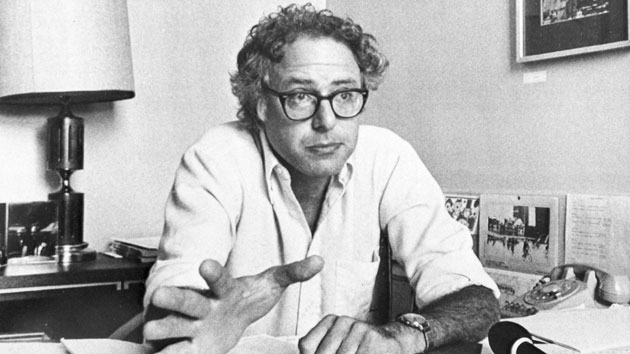

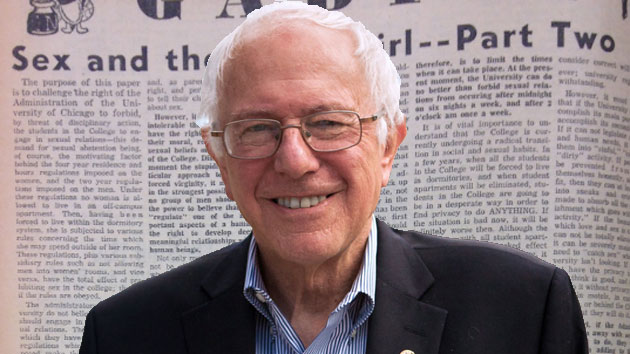

It began with a 2,000-word, ALL-CAPS-laced manifesto in the Maroon, the daily student newspaper, outlining the intellectual case for sexual freedom. Titled “Sex and the Single Girl—Part Two” (a nod to Helen Gurley Brown’s feminist treatise), Sanders attacked the university’s strict student housing guidelines—which prohibited women from living off-campus and restricted visiting access for persons of the opposite sex—with the kind of fire he’d later reserve for capitalists and war hawks.

“[I]s the Administration’s decision in favor of forced chastity, and the right to punish violators of it, based on scientific and rational opinion (the only kind of opinion which students should accept), or is it simply based on a combination of the Bible and Ann Landers?” he asked.

“In my opinion, the administrators of this university are as qualified to legislate on sex as they are to mend broken bones. One can best use an old saying to describe their actions; that their ignorance of the matter is only matched by their presumptuousness. If they dislike sex, or if they think that it is ‘dirty,’ or ‘evil,’ or ‘sinful’ that is their misfortune. It is incredible, however, that they should be allowed to pass their attitudes, or neuroses, on to the student body.”

“Not only must the administrators not be allowed to forbid students who desire sexual intercourse from being able to have it, but they must also not be allowed to prevent a man and a woman from spending a night in conversation, or from simply studying together, alone,” he wrote.

“Who is to measure the value that a group of people, or two people, can receive as a result of a night’s conversation? How are the administrators so knowledgeable that they can say that on long and intimate conversation, which might extend beyond one o’clock in the morning, is not worth more to the people who participated in it than a year of academic education? What do the administrators know about education or about life?”

But, Sanders concluded, the university’s policies aimed at preventing sex among the students wouldn’t work. Students would simply have sex in places other than their dorms:

If the beauty and joy which love and sex is composed of can not be totally eliminated, then it can be severely maimed by the need to ‘catch sex’ when the University isn’t looking. If people can not have the privacy to do what they think is good, and right, they will do it without privacy. They will do it in motels, in cars, on the Midway, or behind the Chancellor’s house, but they will do it.

The manifesto was polarizing. Over the next few days, the paper’s “Gadfly” section was filled with responses praising and condemning the piece. “I wish that the administration would allow Mr. Sanders to practice sex more freely,” one student wrote, because “he might end up a parent and learn a little responsibility.” An alum—a former psychology professor who penned a syndicated column on parenting—wrote in to critique Sanders’ “illogical, or uninformed” argument, and sent the newspaper a handwritten pamphlet called, “Telling your teenagers about sex.” She asked that it be delivered to the future senator. (It was.)

By the time he unleashed his broadside against dorm visiting hours, Sanders already had a reputation as a rabble-rouser. A political science major, he was, by his own admission, “not a good student.” Instead of studying for his classes, he preferred to spend long hours pursuing his own interests—Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, John Stuart Mill, Wilhelm Reich—in the library basement, and generally raising hell.

The campus Sanders arrived on in the fall of 1961 would never be confused with Berkeley circa 1969, but it was a welcome climate for a range of liberal activists in spite of its stodgy reputation. (Weather Underground cofounder Bernardine Dohrn was a year behind Sanders, and Sanders worked on the anti-segregation campaign with Lula White, a Freedom Rider who was studying at the law school.) During his first year in Chicago, a campus scandal erupted when an interracial group of students looking for a place to rent uncovered systematic housing discrimination in university-owned apartment buildings. Apartments that were open to white students would mysteriously go off the market when black students came to inquire, and then just as quickly open up again. The university at first denied any wrongdoing, but later admitted to discriminating in specific cases; if it acquired an apartment building that was segregated, the building would remain segregated.

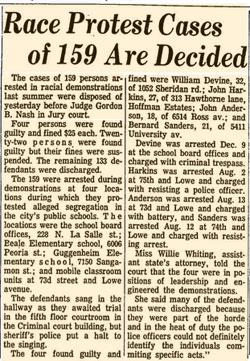

The campus chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, the national civil rights group that organized the Freedom Rides, decided to take action. And Sanders helped organize a sit-in at the office of the university’s president, aimed at making him reverse the school’s discriminatory policy. The sit-in lasted for 15 days, as CORE worked out a compromise with the administration—it would vacate the premises if the university included representatives from CORE in a new commission that would study the housing issue.

During his junior year, Sanders, by then president of the university’s CORE chapter, led a picket of a Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Chicago, part of a coordinated nationwide protest against the motel and restaurant chain’s racially discriminatory policies. Sanders eventually resigned his post at CORE, citing a heavy workload and took some time off from school.

But he remained active on civil rights. At the time, the University of Chicago was in the midst of a massive urban renewal campaign to remake Hyde Park, a mixed-race neighborhood on the city’s South Side. The result was the eviction of many poor black residents. Sanders, as he would throughout his career, viewed the conflict in his backyard as a piece of a much larger issue, and penned a letter to the editor of the Maroon in February of 1963:

To attempt to bring about a “stable interracial community” in Hyde Park without hitting, and hitting hard, the segregation and segregation mentality that exists throughout this city, is meaningless. Hyde Park will never solve its racial problems until these problems are solved throughout the city. Segregation (in the form of “benign quotas”), the promise to white people that Negroes will not be freely admitted into the neighborhood, cannot work on any long term basis.

In the summer of 1963, Sanders took a bus to Washington, DC, to attend the March on Washington. That same summer, he was charged with resisting arrest during a demonstration against segregation in the city’s public schools, and fined $25.

Civil rights weren’t his only passion. Sanders was also active the Young People’s Socialist League (“Yipsel”), a leftist organization which advocated for the “social ownership and democratic control of the means of production and distribution,” but was explicitly anti-communist. (It fielded an intramural football team called the Budapest Eight, in honor of the Hungarian revolution that was suppressed by the Soviets, and enjoyed a rivalry with another squad of leftists called the Flying Bolsheviks.) When LBJ aide Sargent Shriver visited campus during Sanders’ senior year to make his pitch for the new Peace Corps, Yipsel organized a picket. In an open letter in the Maroon, the group explained why: “Mr. Shriver, those who are sincerely interested in economic and social justice will not serve as a front for your capitalist system; instead they will oppose it in any way they can.”

Sanders and his cohorts succeeded in nudging the university forward on civil rights over the course of his three years on campus. But it was a struggle. The committee to study the university’s housing practices, for instance, was a far from satisfying outcome for many of the student demonstrators, Sanders included. (When the journalist Rick Perlstein brought up the subject of the compromise in a recent interview, the Senator issued “a weary sigh.”) And after the initial furor over Sanders’ sexual-freedom manifesto died down, life on the quads returned to normal—late-night curfews and all. In that sense, it was an appropriate lesson for a young activist who would go on to spend most of his political career as an outsider. Lasting political change doesn’t come overnight. Even if you use ALL CAPS.

Additional reporting by Alec Goodwin.