On December 30, 2012, as part of a series called Drugged, the National Geographic Channel aired an hourlong documentary about a 28-year-old named Ryan Rogers. It appeared to be a classic tale of a drunk trying against the odds to sober up, albeit with especially harrowing footage and an unusually charismatic protagonist, often shown with a radiant smile on his handsome face. In one scene, Ryan, in the midst of another day of drinking vodka straight out of the bottle, vomits into the trash can next to his armchair as his distraught grandfather looks on. In another, he roils around the passenger seat while badgering the elderly man to drive him to the liquor store.

“I apologize, you guys,” Ryan says to the camera crew in the backseat. Without a drink, “I can’t even focus or think or even understand anything.”

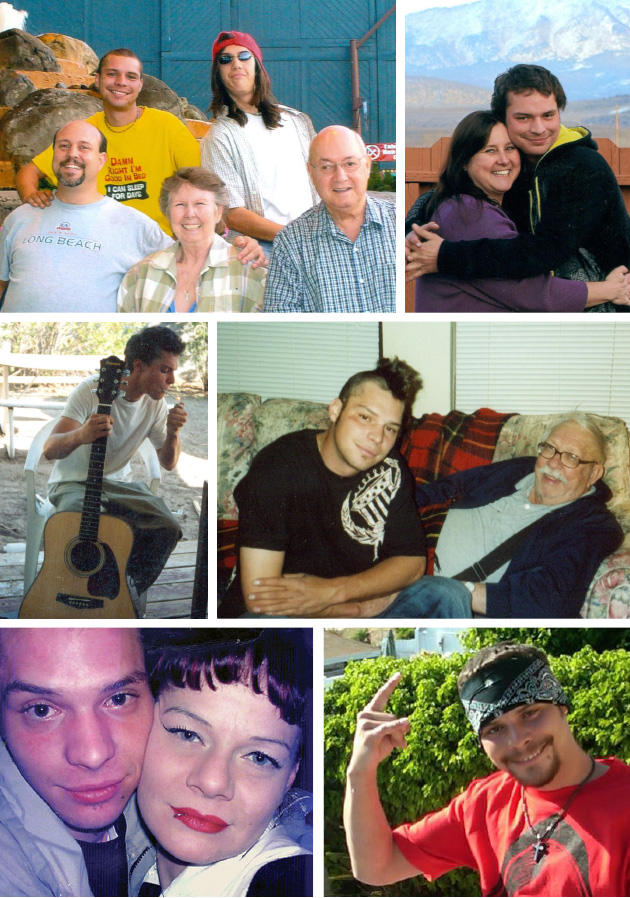

These scenes of craving and self-ruin unfold along the idyllic shores of Ryan’s home near Lake Tahoe, with a cheerful, late-spring alpine light dancing in the pines. During the rare moments of relative calm, Ryan’s warmth and a loving, if fraught, relationship with his family reveal someone who might have a shot at kicking addiction.

This episode of Drugged focused on the medical consequences of alcoholism, so the British production company, Pioneer Productions, followed Ryan until he entered a recovery program, which the company arranged in exchange for his willingness to lay bare his inner turmoil. Ryan’s first stop was a Texas medical clinic, where he underwent a comprehensive evaluation. After palpating his pancreas and liver, the doctor told Ryan that parts of his body were “screaming and dying” as a result of all the alcohol. The hip he broke when he fell off his bike, drunk, while pedaling to the liquor store never healed, leaving him with a rolling limp and in constant pain. At one point Ryan had permission from a psychiatrist to alleviate his withdrawal with some vodka, which he knocked back with an orange soda chaser in the men’s room. Then came the pivotal moment, a staple of addiction reality shows: the interview when the psychiatrist asked if he was willing to go into rehab.

Ryan said he was terrified, but vowed, “I want to amaze people, to let them know: I was gone, but here I am.”

The next day, Ryan arrived at Bay Recovery, a luxurious San Diego center where treatment ran about $1,800 a day. In a baggy white T-shirt, sagging jeans, and a blue bandanna, he carried his navy-blue duffel bag from a taxi to the front door of his new residence, one of several Bay Recovery houses in a neighborhood overlooking Mission Bay and SeaWorld. His room was in a tree-shaded four-bedroom house, set back from the road.

Ryan looked at the ocean and the verdant lawn. “I might not want to leave,” he said. The frame froze on his smiling face.

“Ryan took a courageous step,” the narrator intoned. “But 17 days into rehab, he died. He was only 28 years old.”

But things weren’t quite that simple. A look at the government records surrounding Ryan’s case—and the rest of the poorly regulated rehab industry—suggests that it might not have been just the drinking that killed him: It was the treatment, as well.

The documentary touched a chord with viewers. “I’m sitting here just fucking devastated,” one wrote on Reddit after the film was posted on the site. “Good God, that was absolutely crushing,” another wrote. “I was rooting so hard for him.”

Ryan’s story is a very specific tale of addiction and loss. But it’s also a case study of the fragmented, expensive, and poorly regulated rehab system. Desperate families struggle to find affordable treatment. Those who do all too often discover facilities subject to minimal standards, with regulators who do little to track what happens to patients or to assure that programs are following evidence-based best practices.

At the time of Ryan’s death, California’s medical board had opened the latest of four cases against Bay Recovery’s executive director, Dr. Jerry Rand. Among the concerns that they cited was the death of another patient several years before. And yet the center had been allowed to stay in business, leaving Rand responsible for Ryan and scores of other vulnerable addicts.

Of America’s estimated 18.7 million alcoholics, only 1.7 million—8.8 percent—are treated in specialized facilities, according to a 2012 report by Columbia’s National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. That five-year study reviewed more than 7,000 publications, analyzed five national datasets, conducted focus groups and surveys of addicts and treatment professionals, and investigated how rehab centers are licensed. Its conclusion: “Despite the prevalence of these conditions, the enormity of the consequences that result from them, and the availability of effective solutions, screening and early intervention for risky substance use is rare, and the vast majority of people in need of treatment do not receive anything that approximates evidence-based care.” Nine out of 10 people with alcohol or drug addiction, it said, get no treatment at all.

Compounding the problem is the fact that treatment is often not covered by insurance, but paid out of pocket by addicts and families. Traditionally, private insurance has covered 54 percent of Americans’ health care costs, but only 15 percent of alcohol addiction treatment. Obamacare—which requires many government-subsidized health plans to cover treatment—stands to improve matters, but quality of care remains a serious problem. While residential treatment programs must be licensed at the state level, standards vary widely. “For no other health condition are such exemptions from routine governmental oversight considered acceptable practice,” the Columbia report concluded.

A great deal of research supports modern evidence-based approaches to addiction, often involving medically supervised withdrawal, medication to help with withdrawal symptoms, support groups, and cognitive behavioral therapy. But because there are no national standards, the Columbia study notes, “patients face a patchwork of treatment programs with vastly different approaches; many offer unproven therapies and little medical supervision,” even at centers pushing “posh residential treatment at astronomical prices.”

Part of the problem is that alcohol and drug abuse have been seen less as medical conditions than moral failings requiring self-discipline, according to Scott Walters, a University of North Texas psychologist who has studied addiction treatment. The model popularized by Alcoholics Anonymous, though effective in many cases, is not based on modern science or medical research. One result are clinics staffed by “counselors” who in many states are required to have only minimal training in responding to the serious medical problems that addicts like Ryan often face.

“There’s really no quality control,” Dr. Mark Willenbring, a former director of treatment and recovery research at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, told me. “The consumer is hard-pressed to know what’s what.”

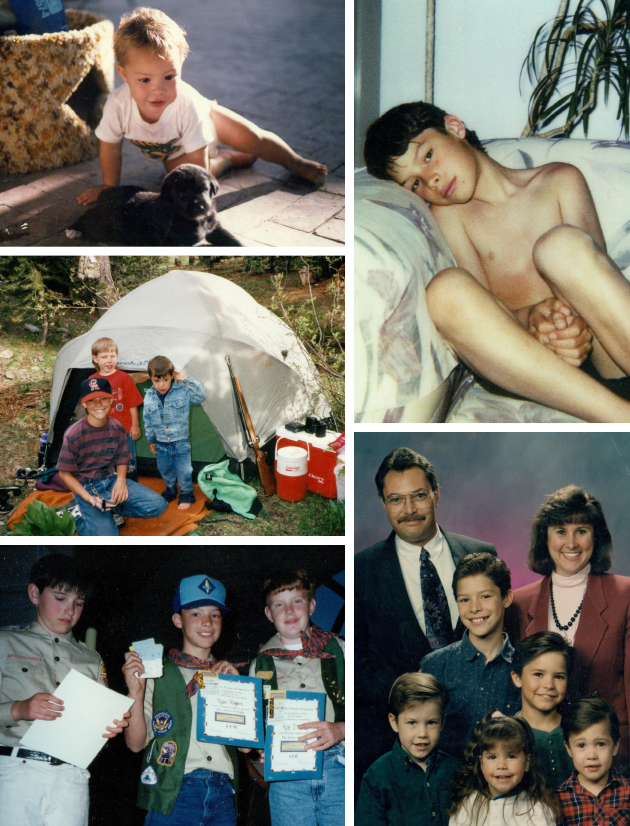

Ryan’s mother, Genene Thomas, and his father, Tim, met when she was 16, he was 18, and they were both working at restaurants in the casinos that line the southern shore of Lake Tahoe. When she was 20, they married, and went on to have four sons.

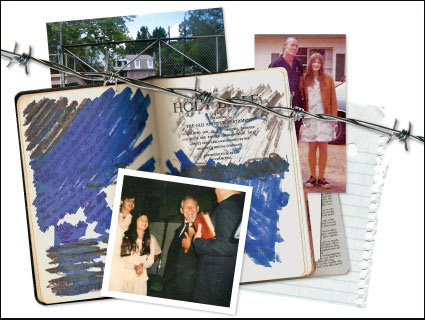

Now 51, long divorced and remarried, Genene welcomed me into the living room of her cozy ranch house, filled with Western memorabilia and sepia-toned photos of her family wearing cowboy outfits. Genene has a tendency to smile when other people might cry. Some viewers of the documentary said she came across as cold, but she confesses that she just shuts down when confronted with overwhelming emotions. Since Ryan’s death, she’s filled stacks of notebooks with thoughts about her son.

When Ryan was growing up, the family moved a dozen times, across the country: Tahoe to New Jersey, back to California, Colorado, and even Hawaii. “Everyone would ask if we were in the military,” she said. “But Tim was just restless.”

He was also dangerously unpredictable and seriously mentally ill: Diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, he drank and heard voices. Some days he organized scavenger hunts for his kids; others, he’d smack them around. Once Tim hit Genene for refusing to give him the bullets he wanted to use to commit suicide. When Ryan was 10, Genene had had enough and took the children to live in a safe house. After about two years of moving around, she took the boys to Las Vegas, where her parents lived.

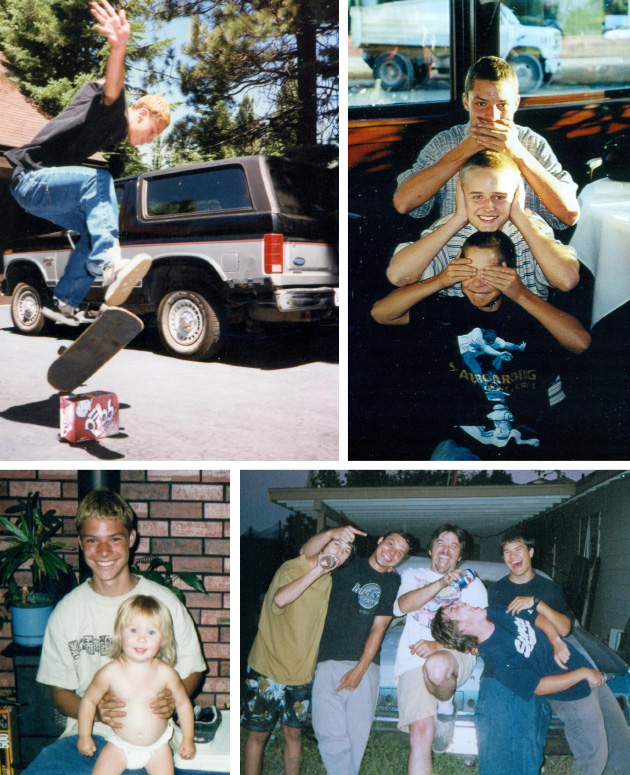

Ryan grew into a cheerful teen, so skilled on a skateboard that a local dealership offered to sponsor him. Like many kids in his high school, he drank and experimented with marijuana. He even dabbled with meth, but it didn’t seem out of control. When he was 19, his paternal grandparents asked if he wanted to live with them to help care for his grandmother, who’d always doted on him.

There, in South Lake Tahoe, Ryan met Shaleen Miller, an outspoken 28-year-old single mother with a Bettie Page vibe. Her interests ranged from the British occultist Aleister Crowley to ribald jokes, and it was love at first sight. “There was just something about Ryan,” she said. “Anyone who met him loved him. He had this light to him I’d never seen before.” Shaleen’s two daughters adored him, and they would make up stories together. Soon Shaleen and Ryan were engaged.

But when Ryan’s grandmother passed away, he began drinking more heavily. A year and a half later, in 2008, his father—who had sobered up and reengaged in the lives of his sons—died of a blood clot at age 47. Ryan helped his grandfather clear out Tim’s room in a Carson City hotel and soon spiraled further out of control. These two deaths marked a turning point in Ryan’s life. Genene grasped the scope of the problem when she found him unconscious on his filthy bed, surrounded by more than 50 empty vodka bottles of all shapes and sizes. She couldn’t wake him up.

In 2009, Ryan secured a free charity bed at a 30-day treatment program in South Lake Tahoe. He liked it, but once he returned to his familiar surroundings, he started drinking again. (The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism notes that 90 percent of alcoholics will experience at least one relapse during their first four years of sobriety.) Over the following two years, he was hospitalized several times for alcohol poisoning, including a stint lasting more than a month in intensive care.

In an attempt to jolt Ryan from his addiction, Shaleen broke off their engagement, but she remained determined to try to save him from himself. The average wait for subsidized treatment was six months, she and Genene were told, and Ryan would have to call every morning until a spot opened up. This was what he had done to get into the South Lake Tahoe program, but now he was too far gone to pick up the phone.

Desperate, Genene talked to a police officer she knew, and learned that her best shot might be to get Ryan arrested to force him into treatment. It was reasonably well-founded advice: The 2012 Columbia report found that 44 percent of addicts in publicly funded treatment programs are referred by the criminal-justice system, but only 6 percent come in via health care providers. When Genene heard that Ryan had tried heroin, she called the police. But his grandfather bailed him out, and the case stalled.

Then Shaleen stumbled upon a Craigslist ad from Pioneer Productions, a London television production company that was looking for severe alcoholics willing to be filmed in return for free treatment. Shaleen wrote an email and got a call the next day.

Pioneer declined to answer questions about the case, but Ryan’s family says the crew told them that they chose Bay Recovery because the clinic treated chronic pain as well as addiction, making it a good fit for Ryan’s twin struggles with alcoholism and his damaged hip. The clinic’s website boasted of its association with reality television producers like Lifetime and A&E and of the “unequaled” care provided by its medical director, Jerry Rand. Genene never found out who covered the cost of Ryan’s treatment.

Shaleen and one of the Pioneer crew dropped Ryan off in San Diego. “I just lost it,” she told me. For two years, she’d been emotionally preparing for him to die. Now, she allowed herself to take heart.

“Hope can be a bastard,” she said.

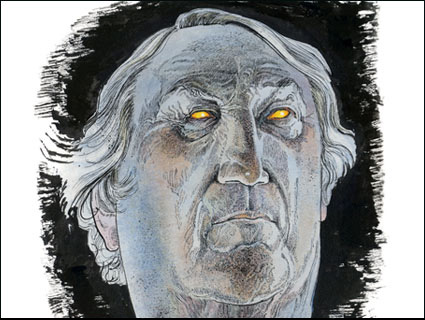

Even as Ryan arrived at Bay Recovery, Rand was fighting for his professional life. In 1988, when he was a general practitioner in Huntington Beach, the Orange County Superior Court had temporarily ordered him to stop practicing. The case came about after a woman whose daughter he was treating for a possible ear infection bolted out of Rand’s office and told a state medical board investigator—who happened to be sitting in the waiting room—that Rand was so impaired that his speech was slurred, his eyes were bloodshot, and he couldn’t even stand up straight. Though Rand sought treatment for his addiction to the pain pills he’d been prescribed after a back injury, the state medical board moved ahead and put his license on probation for seven years. By 1990, he had found work at a recovery center, and in 1992, he launched his own. By 2002, he was an associate director at Bay Recovery.

In 2003, Rand was barred from practicing for 60 days and put on seven years’ probation for what the medical board deemed gross negligence and incompetent treatment of a homeless patient. The board’s report does not detail what ended up happening to the patient, but in 2009—the same year Rand became Bay Recovery’s executive director—the medical board moved to revoke his license entirely. This time, the accusations included gross negligence in treating a 29-year-old woman who drowned in the bathtub at Bay Recovery. Rand had engaged in “extreme polypharmacy,” the board alleged, prescribing drugs to multiple patients with little regard for their interactions. Bay Recovery’s operations were unaffected. The California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP) investigated the drowning and ordered immediate steps to secure medications, but it did not issue any citations for 16 months.

What transpired at Bay Recovery is one example of why the rehab regulatory system is so often described as fragmented. DADP was responsible for licensing the facility, but it’s unclear whether it knew about Rand’s earlier probations. And while the medical board had charged that Rand was admitting patients who were too medically and psychologically unstable to be treated at his facility, DADP never addressed this issue while Ryan was alive.

In 2012, as a nonpartisan investigator for the California Senate, I wrote a report that exposed problems in drug and alcohol treatment facilities, including deaths that occurred when programs failed to monitor medically fragile clients or accepted addicts too sick to be in a nonmedical setting. My report found that DADP failed to pursue evidence of violations after deaths, and took as long as a year and a half to investigate the serious charges. At the time of Ryan’s death, I had been asking the agency for several months why it was allowing Bay Recovery to continue treating clients. I also interviewed Rand about Bay Recovery’s troubles for my report, but he was dismissive. The woman who died had hoarded drugs, he said, and had previously overdosed. He refused to talk about Ryan’s death. I was not able to reach him for this story.

Ryan did not have a cellphone with him, but he borrowed other residents’ phones to update Shaleen. He told her that detox—the first 72 hours without a drink—was not as bad as he had feared. He said he was “eating like a pig,” putting on weight, and could not remember when he’d felt so well. He joked that he was having a tough time sitting in a hot tub overlooking the ocean. And he was making friends with staff and fellow patients. “Everybody loved him,” Kanika Swafford, a residential technician at Bay Recovery, told me. “He never felt sorry for himself. He never blamed anyone for the choices he made.”

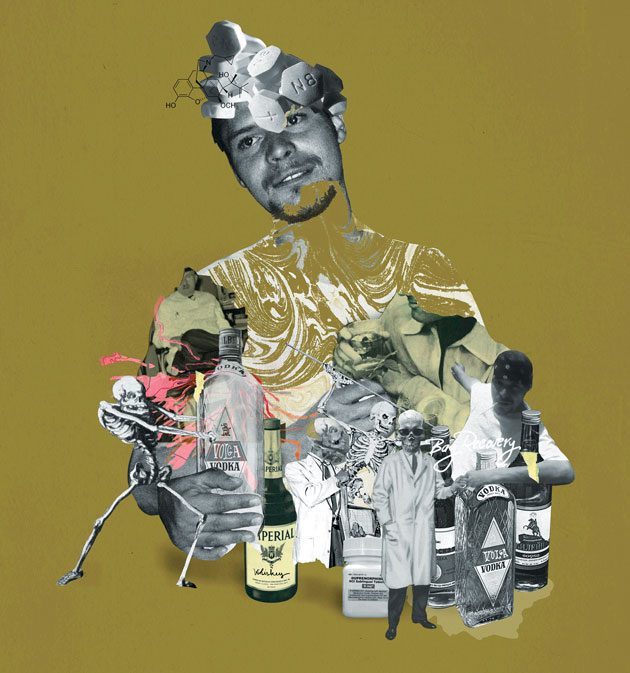

On May 30, 10 days after Ryan arrived, Rand started him on buprenorphine, or “bupe,” which is often used to treat opiate addicts and may also help those who suffer from chronic pain. But it is not for everyone, and it came on top of a whole cocktail of other medications.

The day after starting on bupe, Ryan began to feel sick, according to a later report by the San Diego medical examiner, and in the following days he rapidly deteriorated. Sweaty and disoriented, he now could not hold a conversation. He urinated on the floor and tried to set things on fire. He grabbed at objects that were out of reach and tried to light a nonexistent cigarette. He told a staff member, “Thank you for the sandwiches; my ride is here.” One resident filed a complaint to Bay Recovery’s management, stating that Ryan was “hallucinating, talking to himself, stumbling about and almost falling down the stairs” and had turned a “gray-white color.” A residential technician told a counselor and one of the managers that Ryan needed medical attention.

The evening of June 5, a 20-year-old medical assistant named Giselle Jones heard banging from Ryan’s bedroom and found him on the floor of his closet, digging frantically through his things. She and a resident named Robert tried to put him back in bed, but he kept falling out, getting so agitated that he tried to crawl out a window. Jones tried to reach Rand and his brother Mitch, who was a manager of Bay Recovery, several times.

When Rand finally responded to the call, he prescribed more Ativan, an anti-anxiety medication, and Risperdal, an antipsychotic. Jones hesitated. The charts noted he’d already had two prior doses of both drugs earlier that evening. Was Rand certain she should give Ryan more? Even after he said yes, she called her manager, who told her to follow the doctor’s orders. She did, and 20 minutes later Ryan became listless. Jones tried to get him into bed, but every time she managed to move him, he collapsed. She watched as Ryan’s breathing became more labored. His pulse stopped for five minutes. Jones tried to reach Rand again, but there was no answer. Then she called her manager. Finally, at 3 a.m., she called 911. Robert, the other patient, performed CPR on Ryan. They waited for an ambulance.

At 3:40 a.m., Ryan was pronounced dead.

Later that morning, Shaleen tried to text Ryan via one of the other residents’ phones and eventually she got a response: “I’ll have the director call you back.” She left more messages, one more urgent than the next. She finally got a call back. “I could get in trouble if they knew I had contacted you,” the person said. “But we all loved Ryan so much.”

“I heard ‘loved’ and I just collapsed,” Shaleen said. She dropped the phone. Soon after, a police officer, whom authorities in San Diego had asked to contact the family, appeared at Genene’s door.

The San Diego medical examiner found that Ryan had died of acute respiratory distress syndrome, in which damage to the lungs prevents oxygen from reaching the blood. The deterioration apparently began around the time Rand started him on bupe, which—along with some of the other medications he’d prescribed Ryan—can depress breathing. While the evidence was not conclusive, “the suggestion is somehow that the treatment played a role in the development of the condition,” Dr. Jonathan Lucas, who certified the cause of death, told me.

Twenty days after Ryan’s death, officials from the Drug Enforcement Administration, the medical board, and the state licensing agency raided Bay Recovery and Rand’s home. They had already found that Rand had had employees illegally call in prescriptions for him under the name of another doctor. The state suspended Bay Recovery’s licenses in July 2012.

On September 6, 2012, the California medical board ordered Rand to surrender his medical license and “lose all rights and privileges as a Physician and Surgeon in California.” Police investigated Ryan’s death, and while no charges were filed against Rand, the state did find Bay Recovery “deficient” for failing to get Ryan to a hospital. Residents told state investigators that Rand excessively prescribed drugs with little regard for their interactions. One patient said he hadn’t been on any medications when he arrived, but now was taking at least 10. The state finally revoked Bay Recovery’s licenses and closed the facility in late 2012.

Pioneer Productions sent flowers and paid to have Ryan’s body cremated. It also gave Genene $1,020—money it had raised to help pay for Ryan to get his hip replaced. Pioneer wanted to arrange a memorial service, and a few weeks later family and friends gathered at Monitor Pass, an open slope south of Lake Tahoe with a dizzying view of Nevada’s basins and ranges, to scatter Ryan’s ashes. The crew filmed one last scene.

About a month after the memorial service, Pioneer told Genene that the company was sending someone from London to show her the film. A lawyer appeared a few days later and left Genene alone to watch the documentary on his laptop. She did—twice. The lawyer returned with a form for her to sign that stated she had seen the film and wanted it to run. Genene, feeling strong-armed so soon after losing her son, refused, but when the lawyer called from London a few days later to say that Pioneer had decided not to air the film on the National Geographic Channel, she was heartbroken. Genene and Ryan’s other relatives and friends saw the documentary as his legacy.

Eventually, things were resolved and Ryan’s documentary aired. Many viewers responded, expressing grief as well as concern. “I find this very strange, folks,” one posted online comment said. “The danger zone for any addict is the first 5 days at most. 17 days in he should have been feeling great and refreshed…I don’t think this documentary is telling the honest truth about what really happened to poor Ryan.”

To this day, Shaleen still gets Facebook messages from all over the world, and the shared grief has helped her cope. “That’s just an amazing thing to be able to hold on to,” she said. “Knowing his story made it out there. It gave some kind of purpose to it.”

But Genene continues to write in her notebooks the questions that plague her. Did Pioneer really want to help Ryan, or was it just about ratings? How could the state have allowed Bay Recovery to stay open after the death in the bathtub and the medical board’s case against Rand? Someone was bound to die there, she believes: “If it wasn’t Ryan, it would have been somebody else. And my son had to pay the ultimate price for trying to do the right thing.”