Sipa/AP; sheff/Shutterstock

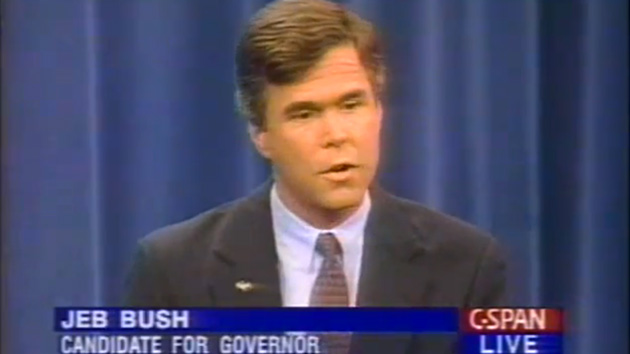

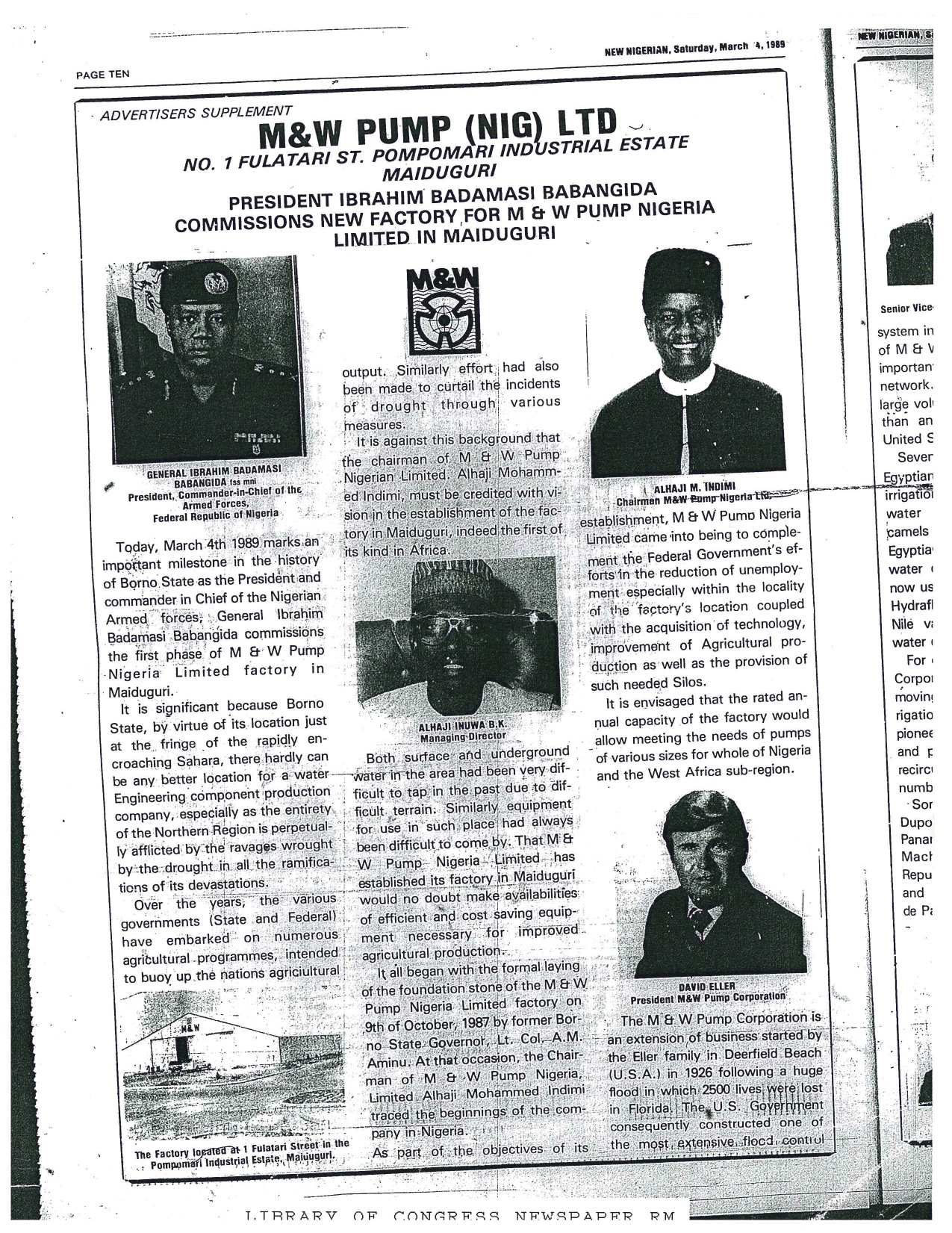

In March 1989, Jeb Bush arrived in Nigeria to a royal welcome. More than 100,000 American-flag waving Nigerians lined the streets of Gombe to watch as the US president’s son was honored with a 1,300-horse “durbar,” a festival typically reserved for heads of state and religious holidays. Bush later met with Nigerian dictator Ibrahim Babangida, who had come to power in a 1985 military coup. They chatted about Cuban human rights and the failed nomination of John Tower, Bush’s father’s pick for defense secretary.

But the president’s then-36-year-old son was not visiting Nigeria on a diplomatic mission. He had come to promote an industrial water pump company. The visit—and the $82 million deal tied to it—would form one of the more controversial episodes of Bush’s business career and dog him for years after he jumped into politics. The deal became notorious because of allegations, outlined in thousands of pages of court documents, that the transaction had been greased through massive bribes to Nigerian officials paid for by American taxpayer money loaned through the US Export-Import Bank. The deal triggered a federal criminal investigation, as well as nearly two decades of civil litigation by the US Department of Justice that in 2013 resulted in a federal jury finding that the water pump company, MWI Corp., had defrauded the federal government of millions of dollars.

Bush has long tried to distance himself from the deal. He was not a defendant in the Justice Department lawsuit, and no criminal charges were ever brought against him or MWI. He has repeatedly said that he didn’t directly profit from the venture or know about any alleged bribery or political influence peddling. But even the less salacious details of the deal, revealed in years of legal filings, don’t reflect well on Bush.

Bush lent his name—and that of his prominent family—to an enterprise with hazards that should have been obvious. Nigeria, then as now, was infamous for its corruption that was virtually inescapable for anyone attempting to do business there. And according to the Justice Department and testimony in the trial, the company Bush was promoting sold overpriced agricultural equipment to an impoverished nation whose people often couldn’t use it. In the process, the deal put the already indebted nation further into hock to foreign creditors.

Bush did not respond to a request for comment for this story, but as he prepares to announce his bid for the presidency, questions still linger about the exact part he played in a deal that the Justice Department said took advantage of both the Nigerian people and American taxpayers.

Bush’s involvement with the Nigeria project began in 1989, the year after his father was elected president, when he formed a partnership with J. David Eller, the CEO of a family-owned Deerfield Beach, Florida, company now called MWI, short for Moving Water Industries. Eller’s father founded the outfit in 1926. It manufactures large-scale water pumps used for flood control, agriculture, mining, and other industrial projects. (Some of its pumps ended up in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.)

Bush and Eller had become friends through Florida GOP circles in the early 1980s. Eller was a big Broward County Republican activist and donor and had landed a slot on the state lottery commission during the administration of Republican Gov. Bob Martinez, who had tapped Bush as his commerce secretary in 1986.

An engineer known for his rumpled hair, wide ties, snakeskin boots, and Bible-thumping Southern Baptist faith, Eller had taken his father’s company global in the 1970s. In the early 1980s, the firm discovered that it could help Nigeria obtain financing from the US Export-Import Bank to buy MWI’s pumps and other equipment, and it ramped up its work in the country. (The Ex-Im Bank, a US government agency, is supposed to promote US exports by providing loans and credit guarantees to foreign countries that agree to buy products from US companies.)

During this period, Nigeria’s military leaders were borrowing extensively from the West to finance dubious projects, many of which never materialized. The money often disappeared thanks to Nigeria’s institutionalized corruption. The most egregious example was the Ajaokuta steel plant. The project was launched in 1979 and, by the mid-1990s, Nigeria had spent nearly $5 billion on the facility, which never produced a single sheet of steel.

When Ibrahim Babangida seized power in 1985, the country was virtually bankrupt. Unable to service its debt as prices plunged for its oil exports, Nigeria’s credit dried up, and its creditors started demanding repayment of billions in loans. In 1986, most of the developed world stopped opening new lines of credit to the troubled country. That same year, Nigeria started begging for international debt relief. It won temporary reprieves, but its debt continued to grow. Under pressure from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, Babangida implemented some economic reforms, including limits on debt-funded imports.

Yet even in this climate, the Export-Import Bank continued loaning Nigeria money, which it used mostly to purchase MWI products. By the time Bush teamed up with Eller in 1988, the Ex-Im Bank had already financed about $87 million of MWI’s sales to Nigeria.

Former MWI employees say that much of the equipment they sold the country was never used, in part because Nigeria didn’t have the infrastructure to utilize it. Brian Stair, a former MWI assistant vice president, explained in a recent interview with Mother Jones that he visited Nigeria in the late 1980s to inspect an MWI shipment of water pumps, which were intended for use by local farmers to irrigate their fields. He found the pumps were gathering dust. The Nigerians “had built sheds to put them under because they weren’t going to put them in the fields right away,” he said. “The fields weren’t prepared. They didn’t have the money to do that.”

Nonetheless, in 1988, the company was cooking up its biggest deal yet: an $82 million package that would ultimately involve about eight different Ex-Im Bank loans to a variety of Nigerian states. These loans would finance the purchase of MWI products—industrial water pumps, pipes, and other products the company told the Nigerians they needed. The project would be worth four times MWI’s annual revenue.

But the deal hinged on two big uncertainties: whether the Ex-Im Bank could be relied upon to provide the funding, and whether various Nigerian officials could be persuaded to sign on to the loans.

Nigeria’s credit was essentially shot, and it was already in default on millions of dollars in loans to US creditors. The Ex-Im Bank had concerns about continued lending to the country. And not every local official MWI approached was enthusiastic about the deals the company was pitching.

That’s where Bush seems to have come in. In early 1989, he and Eller created a corporation called Bush-El to market MWI’s products. The outfit would receive a 3 percent commission on any deals Bush-El helped secure.

Bush has said he never contacted the Ex-Im Bank on behalf of MWI. But in Nigeria, Eller exploited his connection to Bush, suggesting that the then-president’s son was well wired in Washington. Eller made a low-budget promo video for the company’s prospective Nigerian clients that touted his connections to the “highest levels” of the US government and even prominently featured photos of him posing with Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

In his video, Eller noted that Jeb Bush would be joining company representatives in Nigeria for the inauguration of a small manufacturing plant MWI had constructed to develop goodwill with the local officials who were contemplating deals with MWI. “We’re very proud of that and it shows that our government is very interested in what we’re doing in Nigeria and very supportive,” he said in the video.

When Bush hit Nigeria in March 1989, he praised MWI’s work to Babangida, the Nigerian dictator, as an “outstanding example of American private sector cooperation with Nigeria and a contributor to Nigeria’s development,” according to a cable sent to the State Department by US ambassador to Nigeria, Princeton Lyman.

In a separate cable to the State Department, Lyman called the trip “a sensation, no doubt about it…We’ll live off this one for a long while.” President George H.W. Bush later sent Babangida a personal note of thanks for hosting his son.

Two years later, in 1991, Bush returned to Nigeria on MWI business. A May 1991 MWI memo, entered as evidence in the Justice Department’s case against the company, noted that a trip to the country by Bush “may help unlock AAA,” shorthand for Nigerian finance official Alhaji Alhaji Alhaji. According to a MWI spokesman, Bush did not meet with Alhaji or other Nigerian finance officials on this trip.

The following year, the Ex-Im Bank authorized $74.3 million in loans to Nigerian states so they could buy $82 million worth of water pumps and other equipment from MWI. (The states were required to put up about $8 million as a condition of getting the loans.) The loans were authorized even as Nigeria was begging international creditors for debt relief. The Justice Department later observed in its lawsuit, “The fact that MWI was able to obtain Ex-Im Bank financing at all is surprising given the Nigerian Federal Government’s traditionally poor credit history.”

The loans launched MWI into the top tier of American exporters receiving funding from the Ex-Im Bank. According to the Miami Herald, in 1992, MWI ranked ahead US Steel, Motorola, and Union Carbide to become the 13 largest beneficiary of Ex-Im Bank loans.

The 1992 pump deal could have netted Bush-El in the ballpark of $2.5 million, based on the company’s 3 percent commission. But Bush has said that he didn’t make any money off deals underwritten by the US government. “He had established strict rules for his involvement with Bush-El Trading,” the MWI spokesman told Mother Jones. “Those rule precluded him from having any involvement or receiving any compensation whatsoever in any transaction that required US government financing or interfacing with Nigerian or US government officials about such a transaction.” In 1994, when he decided to run for governor of Florida, he sold his shares in Bush-El, eventually receiving nearly $650,000 for his stake.

That might have been the end of Bush’s Nigerian adventure, except for one problem: Robert Purcell.

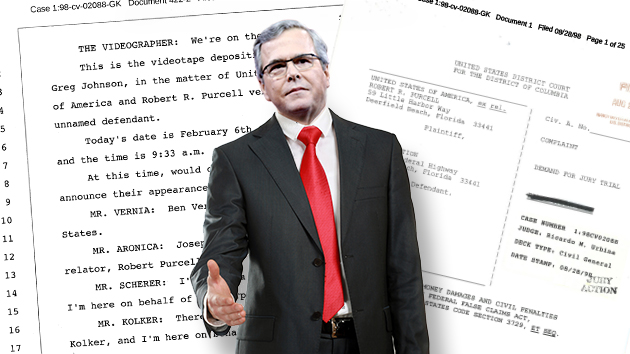

A former MWI vice president, Purcell in 1996 sued Bush-El and MWI for violating his contract, alleging that some of the money that had been diverted from MWI to Bush-El for its marketing work was owed to him. MWI countersued, alleging that Purcell had breached a noncompete contract. This case was settled confidentially in 1998. (Purcell declined to comment for this story.)

But Purcell wasn’t finished with MWI. Also in 1998, he filed a federal whistleblower lawsuit under the False Claims Act against the company. It alleged that MWI had defrauded the Ex-Im Bank by hiding millions in unusual payments to a longtime MWI rep in Nigeria named Alhaji Mohammed Indimi, and it accused Indimi of using Ex-Im loan money to bribe Nigerian officials. The suit triggered a federal criminal investigation. No criminal charges were ever filed, but the Department of Justice ultimately joined Purcell’s civil suit.

A man with reportedly little formal education, Indimi got his start in business “driving a Vespa hauling goat skins,” according to Greg Johnson, who had been an MWI pilot in Nigeria and was deposed in the case before he died in 2003. In the late 1970s, on advice from a Nigerian engineer who went on to become a high-ranking agriculture official, Indimi cold-called MWI’s then-vice president, Juan Ponce, to offer his services as the company’s Nigeria sales representative. A couple days later, he showed up at MWI’s Florida offices, and he told Ponce he could quickly land a $3 million deal in Nigeria, dwarfing MWI’s previous transactions. He soon came through on this promise.

Indimi would go on to become what Ponce called MWI’s “big man” in Nigeria. Indimi was politically connected and became close to Babangida. One of Indimi’s daughters eventually married one of Babangida’s sons. His services were so valuable to MWI that it paid him commissions of over 30 percent for his work, much more than any other sales rep in the company earned. During his 1989 Nigerian tour, Jeb Bush lauded Indimi to Nigerian officials as “a man with vision.”

But the Justice Department subsequently alleged that there was another reason Indimi may have been so successful selling MWI’s products in Nigeria. Of the $74 million the Ex-Im Bank loaned Nigeria to buy MWI’s pumps in 1992, $28 million went directly to Indimi. The Justice Department claimed that a big chunk of that money was used to bribe Nigerian officials. (Indimi could not be reached for comment.)

In the Justice Department’s case against MWI, former employees described Indimi traveling the country with suitcases full of cash and alleged he delivered them to Nigerian officials. MWI denied the bribery allegations and argued at trial that virtually all legitimate business in Nigeria was conducted in cash because of the nation’s poor financial infrastructure. The Justice Department eventually dropped the bribery charges from its case for lack of evidence.

Daniel Smith, a Brown professor who’s expert on Nigerian corruption and who lived in Nigeria during the Babangida era, says that the behavior described in the lawsuit was par for the course in Africa’s most populous country. “The reputation in Nigeria at the time was that you couldn’t get anything done without big bags of money exchanging hands,” he says. “No governor would be worth his salt if he only stole $10 million while he was governor. Those guys are looking to steal tens of millions of dollars, of course more if you’re the minister of petroleum.”

As Greg Johnson, the former MWI pilot, bluntly told the Miami Herald in 2002 about doing business in Nigeria, “Nothing happens until you pay somebody off. You would have to be dumber than a sack of rocks not to understand that.”

Not long after Indimi’s alleged cash deliveries, another American company, Halliburton, and its then-subsidiary KBR, was involved in a bribery scheme to win $6 billion in Nigerian construction contracts. A subcontractor working for Halliburton delivered $1 million in cash to a Nigerian official at an Abuja hotel—the first of several deliveries of a total of $5 million in cash. In 2009, KBR pleaded guilty to foreign bribery charges and had to pay more than $400 million in criminal fines to settle the case with the Justice Department. Halliburton and KBR, which by then had split into independent companies, together had to pay nearly $200 million to settle civil charges with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Several people, including KBR’s former CEO, went to jail for their involvement in the bribery scheme.

Evidence produced during the Justice Department’s lawsuit against MWI showed that the company went to unusual lengths to keep Indimi happy. The company paid for his pool boy, landscaping, housekeepers, and cable television at his Boca Raton home. And it made six-figure payments on his American Express card, paid for insurance on his airplane, and shipped luxury cars to him in Nigeria. MWI said that all of these payments were simply advances on Indimi’s commissions for his legitimate work for the company.

The Justice Department’s lawsuit against MWI dragged on for years. By the time it finally went to trial in federal court in November 2013, the case looked much different from the complaint filed in 1998. The bribery allegations had disappeared after the government conceded it couldn’t prove that Indimi had bribed anyone. Indimi was never deposed or named in the suit; he didn’t make an appearance at the trial.

Ultimately, the Justice Department lawsuit boiled down to whether MWI made false statements to the Ex-Im Bank to hide its $28 million payment to Indimi and fraudulently induced the bank to approve millions in loans to Nigeria. Ex-Im loans are supposed to primarily support American companies and create American jobs, not bankroll individual foreign agents. In addition, outsize commissions to foreign reps are a warning to sign to Ex-Im Bank officials that bribery may be taking place.

MWI had filed certificates with the Ex-Im Bank stating that only ordinary commissions had been paid. But Indimi’s commission was more than five times higher than those received by any other MWI salesperson. A company employee testified that MWI deceived the Ex-Im Bank about Indimi’s commission, believing the bank would reject the loan payments if it learned the truth. Former Ex-Im Bank officials confirmed in testimony that they would indeed have nixed the loans.

The trial raised other questions about the MWI deal. In court, Ponce, the former MWI vice president, said the company marked up the price of the equipment it sold Nigeria many times over—the Justice Department alleged the markups were as high as 500 percent—in part to cover Indimi’s huge commissions. He also testified that Nigeria couldn’t use the expensive equipment it was buying from MWI with its Export-Import Bank loans. “I would say that this was business that was done just for the sake of doing business,” he testified. During the trial, a juror asked him what percentage of the MWI equipment sold to Nigeria had gone unused. “Ninety percent,” he replied.

In an email to Mother Jones, the MWI spokesman said the deals in question were executed over a seven-year period, during which the Nigerian government had experienced a significant amount of instability. “All of the equipment that we supplied was based on engineering feasibility studies on the needs of each of the specific states in question,” he said, explaining that the company had no control over what Nigeria did with the equipment once it arrived there.

During the 2013 trial, prosecutors sought to call Jeb Bush as a witness. But MWI successfully fought his appearance, arguing that the government was trying to create a “misleading side-show” and to “politicize this case and incite the passions and bias of the jury.”

After a two-week trial, the jury determined that MWI had presented false claims to the Ex-Im Bank and found the company liable for $7.5 million in damages, which the judge had the option to triple. But the federal judge presiding over the case ruled that MWI didn’t have to pay any of that—because Nigeria had somehow managed to repay the loans related to its MWI purchases.

Initially, Nigeria had defaulted on the Ex-Im Bank loans that funded the MWI purchases. Yet by 2002, when Nigeria was behind on nearly $1 billion in Ex-Im loans, the country managed to repay the $74 million MWI-related loans, plus $34 million in interest and fees. The judge ruled that the repayment meant the Ex-Im bank had been made whole and the federal government no longer had any damages. But the judge did rule that MWI had to pay $580,000 in civil penalties for the false statements and the 11,000 hours of legal work the Justice Department had invested in the case. The case is now being appealed by all parties.

Today, MWI no longer works in Nigeria, in part thanks to the extremist group Boko Haram, which is active in Maiduguri, where its plant was located. Indimi, who went into the oil business, is now worth about $700 million and is regarded as one of Africa’s richest men. Jeb Bush long ago cut his ties with Eller, who has not been publicly involved in any of Bush’s recent political campaigns. And these days, Bush has joined conservative critics who believe the Ex-Im Bank funds “crony capitalism.” He has called for it to be shut down.