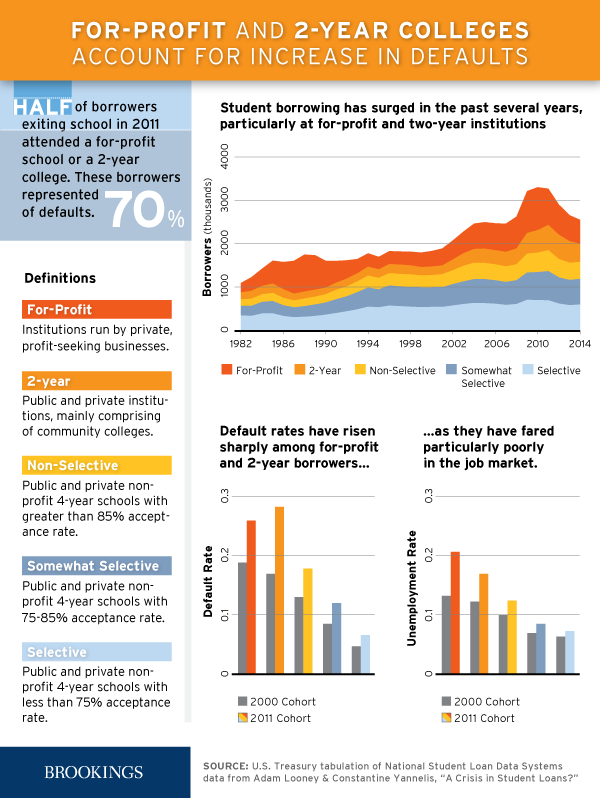

The student loan crisis may bring to mind 22-year-old graduates from four-year colleges trying to figure out how to pay off hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. And while this image may have been accurate before the recession, today’s reality is more complicated: According to a recent report released by the Brookings Institution, the rise in federal borrowing and loan defaults is being fueled by smaller loans to “non-traditional borrowers,” or students attending for-profit universities and, to a lesser extent, community colleges.

As Mother Jones has reported in the past, compared with four-year college graduates, nontraditional borrowers are poorer, older, likely to drop out, and, if they do graduate, unlikely to face bright career prospects. The median for-profit university grad owes about $10,000 in federal loans but makes only about $21,000 per year.

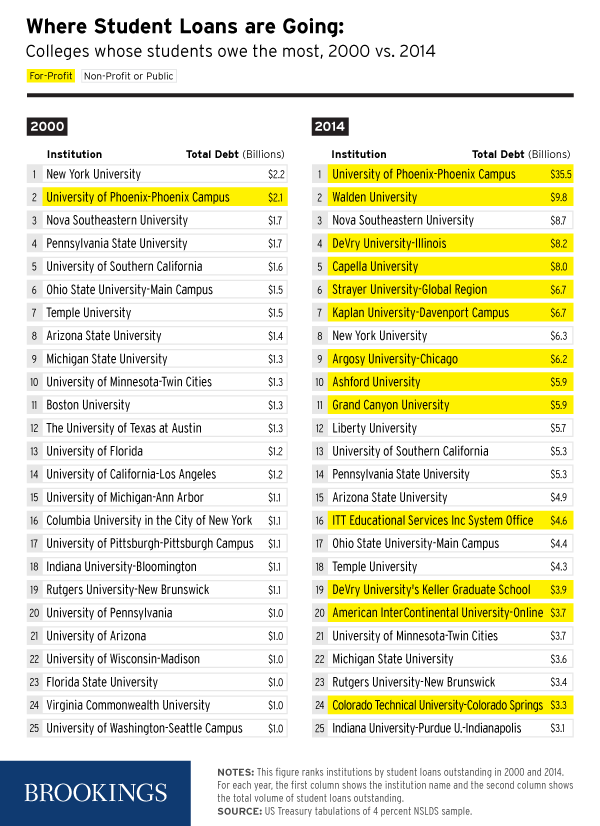

The report, based on newly released federal data on student borrowing and earnings records, shows just how much the economics of higher education have transformed since the recession. In 2000, the 25 colleges whose students owed the most federal debt were primarily public or nonprofit, with New York University taking the lead. By 2014, 13 of the top 25 were for-profit universities. In the same period, the amount of student debt nearly quadrupled to surpass $1.1 trillion, and the rate of borrowers who defaulted on loans doubled.

So what happened? During the recession, students poured into colleges to make themselves more marketable in a crummy economy. Community colleges, depleted from plunging state tax revenues, couldn’t expand to account for this exodus from the job market, so many students—and their loans—ended up at the quickly expanding for-profit universities, which promise short courses in tangible skills.

But students graduating from these colleges have notoriously dim job opportunities—some of the colleges have shut down in recent years after Department of Education probes found them to target low-income students and misrepresent the likelihood of finding a job post-graduation. So with the subsequent influx of students back into the job market—and, for many of them, into low-wage work or unemployment—thousands are stuck with debt.