Shortly after midnight on September 14, 2000, James Ghent slipped out of his Miami home, climbed into his car with a suit, a toothbrush, and a change of underwear, and drove nearly 500 miles to Tallahassee to ask Jeb Bush for his rights back.

The journey, he hoped, would help him close the door on a fraught relationship with the law that stretched back to the mid-1960s. As a teenager, Ghent had experimented with drugs and racked up a criminal record; after returning to Florida from a combat tour in Vietnam, he got hooked on crack cocaine. He turned to stealing to finance his habit and spent the 1980s in and out of prison for a string of burglaries.

One day in 1989, he was released from prison in the morning, attempted to steal a car in the afternoon, and was back behind bars by the evening. “You got to be a dumb MF,” an officer told him. “You just got out this morning.”

Enough was enough. Ghent completed his final prison sentence in the early 1990s and his parole in 1995. He got clean. He remarried and raised a family. He went back to school for a degree in radiography.

But like everyone convicted of a felony in Florida, Ghent permanently lost his right to vote, serve on a jury, and run for office. The only way to regain these rights was to petition the governor for clemency. Ghent believed voting “should always be a right,” but he was also motivated by economic concerns. He couldn’t receive a professional license to practice radiography unless the governor granted his petition. And so on that September morning, Ghent descended into the basement of the state Capitol with dozens of other petitioners for a unique Florida ritual: ex-felons entreating the governor and members of his cabinet for the restoration of their civil rights.

These hearings, held four times annually, begin promptly at 9 a.m. One by one, ex-offenders like Ghent approach a podium, where they have five minutes to make their case. A red light signals their time is up. If the governor recommends clemency, and if a majority of the cabinet members agree—and they almost always do—the ex-offender’s civil rights are restored. If the governor feels otherwise, the petitioner returns home without the full privileges of citizenship.

Ghent was one of the last petitioners on the docket. His hopes rose and fell with the fortunes of the men and women before him. He compared their crimes with his own. Fearing he might miss his turn if he strayed to the cafeteria, he limited his breakfast and lunch to the slim pickings from a nearby vending machine. By the time his name was called, he was racked with stress.

Bush issued his verdict as soon as Ghent concluded his pitch. “I’m going to deny the restoration of civil rights,” he said. He wanted to see Ghent remain on the straight and narrow a bit longer, to prove he had really changed his ways. “I hope you come back, and I wish you well.”

Fifteen years later, Ghent remembers the sting of those words. “He was very dismissive,” says Ghent. The ex-felon wanted to push back against Bush’s decision. But he simply said, “Thank you,” and turned away.

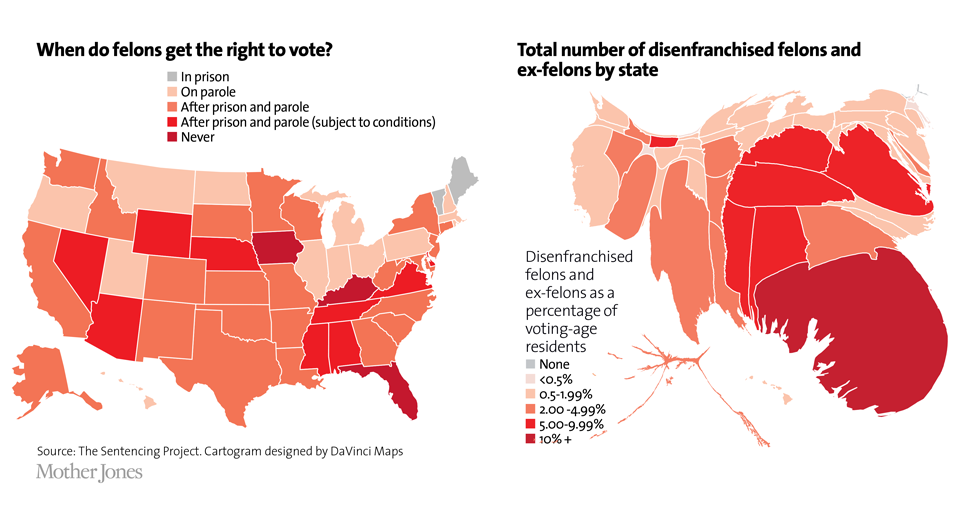

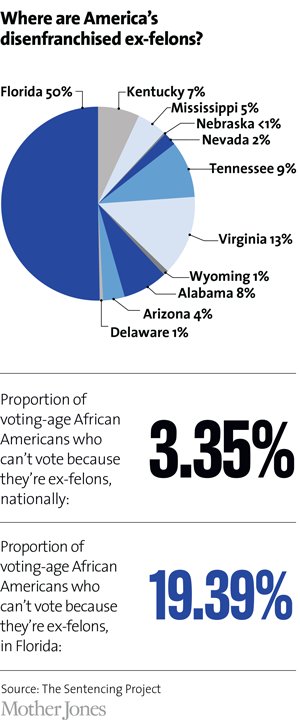

Ghent was destined to remain an unwilling member of an unlucky club: the legions of Florida citizens—disproportionately African Americans, like him—who since the Civil War have been barred from the democratic process because of past convictions. Florida is currently one of three states that permanently disenfranchise everyone with felony convictions, even after they have completed all the terms of their sentences—a practice that today excludes nearly 1.5 million Floridians from voting, including about 20 percent of the state’s black voting-age population. Under Bush, some low-level offenders regained their rights without appearing in person. But for many ex-felons, including some convicted of minor drug crimes, the only way to prevail was to show up and plead for clemency.

The year Ghent stood before Bush at the podium, the consequences of felon disenfranchisement were particularly profound. The 2000 presidential election was ultimately decided by a 537-vote margin in Florida. More than 500,000 ex-felons were barred from the polls, including at least 139,000 African Americans, who vote overwhelmingly for Democratic candidates. Their exclusion almost certainly changed the outcome of the race. The beneficiary, of course, was Jeb Bush’s brother.

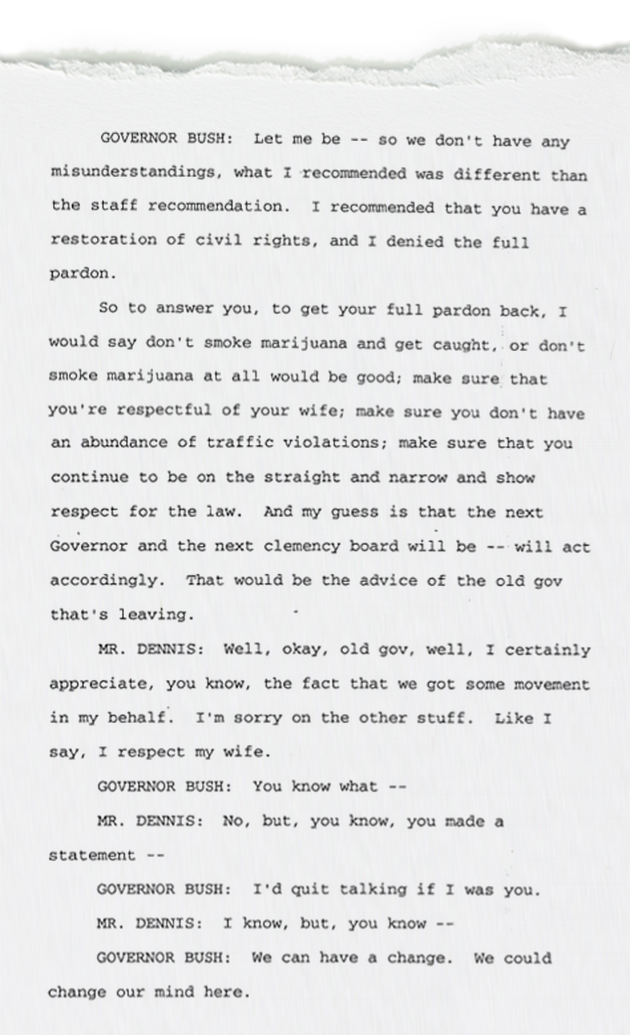

Bush, today a leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, did not invent this quasi-monarchical process. But he did embrace it. Mother Jones obtained more than 1,000 pages of transcripts of clemency hearings held during Bush’s tenure. Together, they provide a glimpse into his moral reasoning as he weighed the worthiness of the appeals by thousands of ex-felons hoping to regain their rights. The transcripts, covering two years of hearings, show that Bush seems to have relied on an entrenched set of personal values in his rulings. If a crime involved alcohol abuse—such as DUI manslaughter cases, which were relatively common—he liked to see several years of complete sobriety before he would restore the person’s rights. He was loath to approve the applications of petitioners he felt were not sufficiently remorseful or did not take full responsibility for their crimes. He sometimes asked wives in attendance to keep their husbands in check. Ex-felons needed to prove, over years of good behavior, that they had reformed. Bush often denied clemency simply because he believed not enough time had elapsed since the completion of the petitioner’s sentence. He did not appear to question the basic premise of his judgments: that the right to vote should be contingent on a citizen’s moral rectitude.

“The governor believes this is a fair process,” a spokesman for Bush said in 2004. At a hearing two years later, Bush said, “It’s very humbling for a human being to pass judgment on others…I worry and I wonder if I get it right.”

Bush’s presidential campaign declined to make the candidate available for comment. In an email, a spokeswoman shared news clippings highlighting Bush’s record on voting rights, including his advocacy for tighter voting restrictions, and said that “he supports vigorous enforcement policies to protect the right to vote nationwide.”

Felon disenfranchisement in Florida has a long and ugly history. Before it became a state, the Florida Territory’s constitution limited felon voting, a prevalent restriction in the nation’s earliest days. But after the Civil War, when Congress made voting rights for African American men a condition for Confederate states to rejoin the Union, the South turned to felon disenfranchisement to undermine the voting rights of newly freed slaves. Florida adopted a new constitution in 1868 that expanded its felon disenfranchisement provision to cover a broader array of offenses, including vagrancy and petty theft.

In a separate attempt to address “the altered condition of the colored race,” Florida created county criminal courts with jurisdiction over such crimes as “larceny, malicious mischief, vagrancy, and ‘all offences against Religion, Chastity, Morality, and Decency'” that were largely targeted at imposing fines, forced labor, and corporal punishment on African Americans. A few years after the new constitution took effect, Robert Meacham, a black state senator, described the county jails as “full of colored people for the most frivolous and trifling things.” During Reconstruction, black men accounted for up to 90 percent of new prison inmates in Florida each year. The majority had been sentenced for some form of theft.

When Bush became governor in 1999, felon disenfranchisement had reached levels unseen in the modern era. Florida’s prison population, now the third largest in the country, had ballooned during the tough-on-crime 1980s and 1990s, with African Americans disproportionately locked up. The result was that by 2010, 9 percent of all voting-age Floridians were disenfranchised ex-felons. Among African Americans, that figure was 19 percent. Throughout Bush’s tenure, from 1999 to 2007, the majority of offenders exiting prisons were black.

“This is, in my opinion, nothing more than a Jim Crow law that we have unfortunately maintained to the current era,” says Ion Sancho, the longtime supervisor of elections in Leon County, which includes Tallahassee.

Ghent’s petition for his rights required him to take time off work, drive nearly 1,000 miles round trip, and navigate a complex application process. “A lot of people don’t have the understanding of the process to be able to go through it,” he says. “I believe sincerely that it’s geared that way so you wouldn’t be able to do it.” Ghent has a saying: “First they lie, then they deny, and then they hope you die.” He made the pilgrimage, he explains, because “I was determined not to die.”

The 2000 election brought national attention to the hundreds of thousands of ex-felons in Florida who had lost their right to vote. Before Jeb Bush took office, Florida responded to a 1998 voter fraud scheme in Miami—a rare case of actual voter fraud—by hiring an outside firm to purge the state’s voter rolls of any felons and deceased voters. The list of about 58,000 names the company drew up was deeply flawed. It contained many Floridians with only misdemeanor offenses, and others with no criminal records at all, sometimes because they had names similar to those of felons. It singled out African Americans, who made up 11 percent of registered voters in the state but 44 percent of the purge list. According to Edward Hailes, a lawyer with the US Commission on Civil Rights, the number of African Americans wrongfully expunged from the rolls who would have voted for Al Gore was 4,752—nearly nine times greater than the 537 votes that handed George W. Bush the presidency. The purge was, as Hailes told The Nation, “outcome-determinative.”

The original disenfranchisement law “had terrible racial and anti-democratic effects,” says Jessie Allen, an attorney who worked on an unsuccessful legal challenge to Florida’s felon disenfranchisement regime in the early 2000s. “But as the 2000 election demonstrated, the state administered the law in ways that exacerbated those effects.”

Under Jeb Bush, Florida undertook a second voter purge—again with a sharp racial skew—in 2004, the next presidential election year. Of the 48,000 people on the second list, 22,000 were black. Just 61 people on the list were Hispanic, at a time when Florida Hispanics, including the Cuban community in Miami, voted solidly Republican. After the media made the list public, and with a potential lawsuit looming, Bush abandoned the purge.

In the beginning, felon disenfranchisement “was racial,” says Sancho, an outspoken critic of both purges. But after the 2000 election, he observed, it “turned into a partisan issue.” In his new book, Give Us the Ballot, journalist Ari Berman argues that the 2000 election inspired efforts to suppress voting across the country, after Republicans witnessed their party’s electoral success in Florida when thousands of Democratic-leaning voters were kept off the rolls.

Voter suppression laws proliferated after the Republican wave election in 2010, and again in 2013, when the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required states with a history of disenfranchising African Americans to gain Department of Justice approval of any changes to voting laws. GOP-controlled legislatures have increasingly turned to voter ID laws that effectively keep minority voters from the polls, and have rolled back early voting days and Sunday voting, when black churches mobilize their parishioners after services. Over the last five years, nearly half of all states have passed laws making it harder to vote.

Felon disenfranchisement has likewise grown under Republican governors, after years of loosening restrictions on felon voting around the country. Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad made felon disenfranchisement permanent in 2011. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan vetoed a law earlier this year that would have allowed felons to vote while on probation or parole. In Florida, Gov. Rick Scott has made the rights restoration process more restrictive than it had been in decades.

“Florida is a purple state,” says Aubrey Jewett, a political science professor at the University of Central Florida. “Many statewide elections are quite close. Keeping potentially tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands off the rolls when a majority of those voters are probably going to vote Democratic, you can’t help but suspect partisan motivation.”

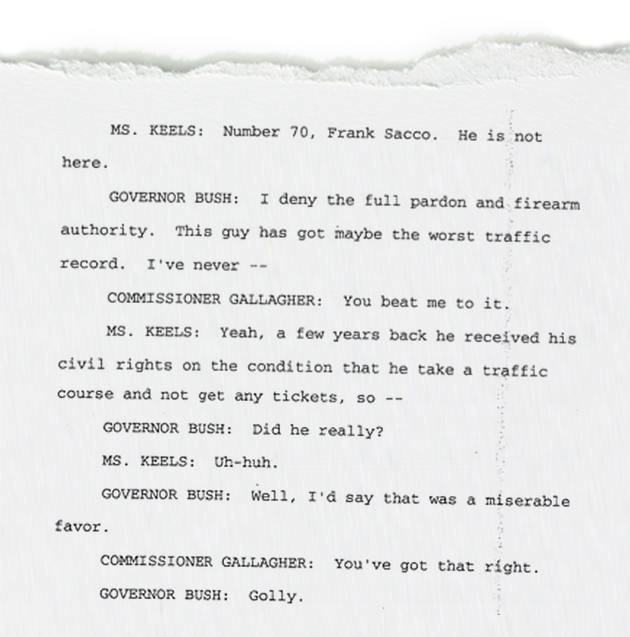

Bush found his role as moral arbiter-in-chief to be “one of the most interesting parts of the job.” He applied some creative metrics to determine whether a petitioner deserved the right to vote. During a March 2006 clemency hearing, ex-felon Tim Jones was explaining why he wanted his rights back—to set a good example for his children—when Bush cut him off. “Tell me about your traffic record,” the governor said. “This is one of the most horrendous records I’ve seen in a long time.”

“My traffic record?” Jones responded, incredulous.

“It’s one signal of whether you respect the rules of society,” said Bush. He frequently grilled ex-felons on their driving records, although Florida residents are among the most likely in the country to get speeding tickets, according to the National Motorists Association. (The New York Times reported this spring that Florida Sen. Marco Rubio and his wife had received a combined 17 citations since 1997.) Bush pointed to Jones’ record, with 30 citations dating back 20 years: “Imagine if everybody drove like you, all in the same place. We’d have chaos.”

Bush issued an ultimatum: Jones could regain his civil rights if he lasted one year without a single traffic violation. That meant Jones could not vote in the gubernatorial or congressional elections that November. “Drive back home very slowly,” Bush warned him. “We’re starting today.”

Bush’s guiding principle during these hearings was that ex-offenders needed to prove their lives were back on track before he would restore their rights. But research shows the inverse to be true: The restoration of civil rights helps ex-felons reintegrate into society. Studies in Florida have found that ex-felons who have their rights restored have a 20 percent lower recidivism rate than those who don’t. “I do the voter registration drives in their communities and see the individuals avert their eyes,” Sancho says of disenfranchised African Americans. “They’re ashamed. They’ve lost their right to vote and they can’t register to vote.”

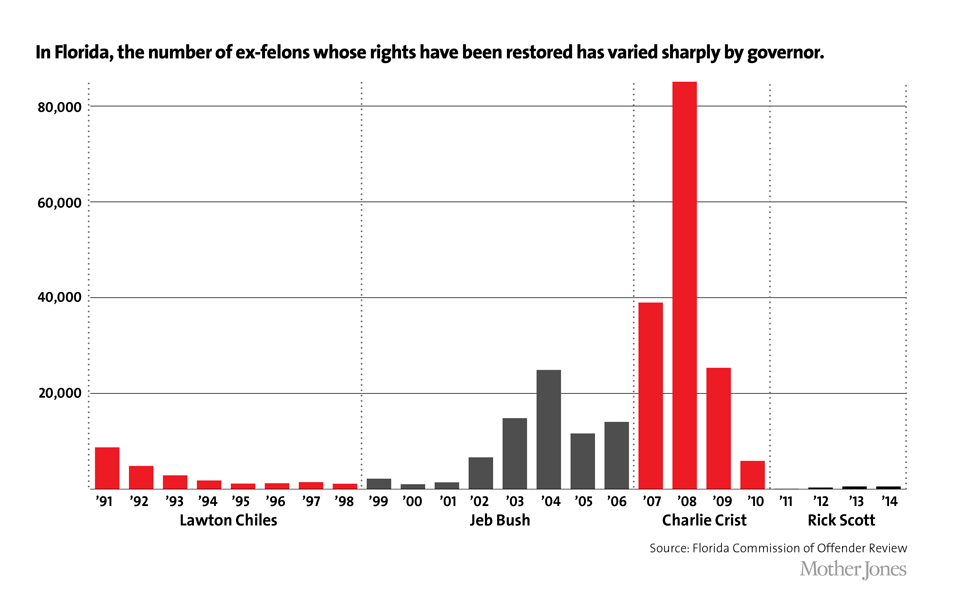

In 2002, black state legislators successfully sued the state for failing to provide ex-felons with the necessary paperwork to apply for restoration, forcing the administration to consider an additional 155,000 applications. To cope with the new workload, Bush revised the rules to allow certain low-level offenders to regain their rights without submitting an application, and he made more people eligible for rights restoration without a hearing. He also simplified the application process by allowing ex-felons to request their rights online, by phone, or by email. At his final clemency hearing in December 2006, he boasted that under his watch, more than 73,000 people had regained their rights without a hearing, a 200 percent increase from under the previous governor, Democrat Lawton Chiles.

Still, the number of disenfranchised ex-felons grew under Bush, as rights restorations failed to keep pace with the tens of thousands of offenders who exited the criminal justice system each year. Ultimately, Bush approved just one-fifth of the 385,522 applications for civil rights submitted during his eight years in office.

Bush’s successor, Republican Charlie Crist (who has since become a Democrat), made the restoration of rights automatic for nonviolent offenders who met basic criteria. In 2008, more than 85,000 ex-offenders had their rights restored—more than during Bush’s entire tenure. But even under Crist, those numbers waned as the docket of outstanding low-level cases shrank and budget cuts meant fewer staff to work through the backlog. In his final year in office—as he was gearing up for a Republican Senate bid, with a tough primary challenge from Rubio—fewer than 6,000 people had their rights restored. Under the current governor, Scott, restorations have nearly ground to a halt, with just 78 applications approved in 2011.

Churches and civil rights groups like the ACLU are collecting signatures for a citizens’ initiative that would expand the restoration of voting rights, but it’s not likely to appear on the ballot before 2018. Howard Simon, executive director of the state’s ACLU branch, calls lifetime felon disenfranchisement “the great unfinished business of the civil rights movement in Florida.”

Despite undeniable evidence of systemic racial disparities in Florida’s voting restrictions, on a case-by-case basis the hearing transcripts from Bush’s tenure reveal a haphazard process. Did the ex-offender sufficiently convey his regret? (“People that come here need to have in their hearts some sense of remorse for what they did,” Bush said in denying one man’s rights in June 2000.) Did an ex-felon ask too many questions? (“I’d quit talking if I was you,” he warned another man who continued to ask questions after getting back his civil rights. “We could change our mind here.”) Could the petitioner take time off work to make the trip to Tallahassee? (Dozens of ex-offenders had their applications denied simply for failing to appear.) Despite Bush’s fondness for his own criteria—time elapsed, speeding tickets accrued, alcohol consumed—winning the right to vote often came down to luck.

“It reminds me of the serfs entering the castle and asking for assistance from the king,” says Sancho. “And depending upon how they feel that day, you might get it—or not.”

When Harold Finocchiaro appeared before Bush, near the end of Bush’s last day of clemency hearings in 2006, the governor seemed in high spirits. Finocchiaro’s frank account of his past criminal behavior endeared him to Bush, who playfully interjected his thoughts as Finocchiaro told his wild tale.

Finocchiaro described how drug and alcohol abuse led him “to kind of go crazy” during a midlife crisis. He frequented Orlando’s topless bar scene and developed a cocaine habit. “Being a drug user, you try to sell drugs to use drugs, and that’s what I was doing,” he acknowledged. Eventually, the law caught up with him. On his attorney’s advice, Finocchiaro fought the charges all the way to trial, which resulted in a longer sentence than if he had taken a plea bargain. He had been in denial, he said, that he deserved any punishment at all.

“But you admit you committed a crime, right?” Bush interrupted. “Bad lawyer aside.” Finocchiaro hastily agreed he was guilty. “It sounded like you were excusing—blaming the lawyer,” Bush added. “Because I’ve done that sometimes, but not in this kind of setting.”

Finocchiaro continued with his story. “Now I’m in prison, and I’m unhappy, so I walk away,” he said. “I actually leave.” Confused, Bush interrupted again to ask how he managed that. “It was a low-security penitentiary,” Finocchiaro explained.

“There you go,” Bush replied, clearly enjoying the repartee.

Finocchiaro eventually returned to prison and joined Alcoholics Anonymous. By the time of his hearing, he had been sober 10 years. He owned a small business. He checked all of Bush’s usual boxes. The governor delivered his verdict. “I recommend that we grant the restoration of civil rights,” Bush said.

He commended Finocchiaro for making the trek to Tallahassee. “It’s good to come up,” Bush said. “You probably would have been denied had you not been here.”

Ghent’s thousand-mile journey, on the other hand, left him where he started. But he decided not to abide by Bush’s rejection. In a twist befitting Florida’s topsy-turvy voting system, Ghent went ahead and cast a ballot in the 2000 election, according to Miami-Dade County records. And while thousands of other Floridians were wrongfully barred from the polls, Ghent’s vote was counted. He went on to vote in several elections before his rights were ultimately restored, without a hearing, in July 2005, after Bush’s loosened rules had gone into effect. Ghent can’t remember why he voted in 2000 or how it happened. “Maybe,” he says with a laugh, “I slipped through the cracks.”

It’s further evidence of the lack of fairness in determining who gets to vote in Florida—a system that’s “flawed to a fault,” Ghent believes. “Most people don’t understand what disenfranchisement means,” particularly to African Americans, he says. “It means a lot. It means a lot.”