<a href=http://www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/GOP-2016-Carson-Religion/618c07c771f14940b5f642434cff4fcd/8/0>Brennan Linsley</a>/AP

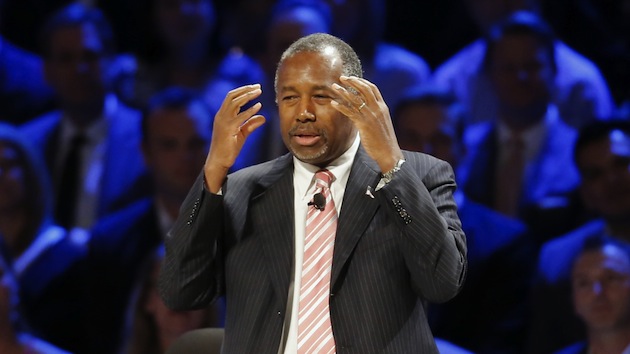

Ben Carson, one of the GOP 2016 front-runners, is a retired neurosurgeon who has never held office, but he asserts that a candidate’s faith (and character) is a more important qualification for the job of president than political experience. And he routinely points out that he has plenty of Christian faith. So is there anything wrong in scrutinizing aspects of Carson’s religious beliefs?

Recently, I’ve written twice about Ben Carson and his religion. In one article, I noted that Carson, a committed and practicing Seventh-day Adventist, last year indicated that he accepts one of the church’s core teaching: that during the soon-to-come End Times the government and the rest of the world’s religions will join with the Antichrist to persecute Seventh-day Adventists (because they observe the Sabbath on Saturday, not Sunday) and that this will result in the imprisonment and possible execution of members of this church. In another piece, I examined whether it might be politically significant if Carson agrees with the church’s view—based on the dramatic and conspiratorial prophecies of its prophet Ellen White—that other evangelical Christians are destined to end up working with Satan and the Catholic Church against Jesus Christ when he returns to Earth.

After I posted those articles and gently noted on MSNBC’s Hardball that there are “serious issues” about Carson’s allegiance to the Seventh-day Adventist church, conservatives howled with outrage. The Media Research Center, which boasts it is dedicated to “exposing and combating liberal media bias,” huffed that I had “claimed that Carson’s religious needs to be investigated because it professes an end time.” (“Guess what, David?” the MRC declared. “All the Abrahamic religions do: Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. It’s not a question of if, only when.”) This conservative outfit added, “So take your religious bigotry elsewhere, Corn.” Breitbart griped that I had “called into question…Carson for his faith.” Rightwing site WND groused that I had launched “a seething attack on Dr. Carson’s denominational preference” and slammed it as a “bigoted assault.”

Yet is it unfair to ask whether Seventh-day Adventist theology would shape Carson’s approach to governing, should he be elected president? In a 2013 interview with the church’s official news service, Carson was queried, “Are there ever any times when you feel it’s best to distinguish yourself from the Seventh-day Adventist Church and what it teaches?” Carson replied, “No, I don’t.” (He added that he fully accepts the church’s stance that God created the world literally in six days.) This leads to several obvious questions. Church officials proclaim that the End Times are close at hand—within a few years. If Carson shares this belief, how might it affect his thinking about climate change or, say, events in the Middle East? Does he perceive evangelicals Christians—include those flocking to his campaign—as future foot soldiers for Lucifer? Does he share the church’s persecution complex and its somewhat paranoid view of the world (that is, that the government, doing the devil’s work, will soon be rounding up Seventh-Day Adventists)?

Carson himself has suggested that religion is not out of bounds in politics, noting that a Muslim should not be elected president. And in an email solicitation that Carson sent out on October 29—titled “I’m not a politician”— he declared, “I believe that traditional ‘political experience’ is much less important than faith, honesty, courage.” Faith is at the top of his resumé. That’s a sign it warrants vetting. And a prominent member of the Seventh-day Adventist church agrees.

Loren Seibold, who is a pastor with the Ohio Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, last week published an article in Spectrum, an independent Adventist publication, that seriously engaged—and wrestled with—the questions inherent in the articles I had written. He began:

When a friend sent me David Corn’s column for Mother Jones a few weeks ago, it was like getting hit with bad news I already knew. Sooner or later, someone was going to peek behind the first serious Seventh-day Adventist presidential candidate, and begin to scrutinize the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Corn gave a fairly accurate description of historical eschatological narratives about how the Papacy, through the agency of the United States government, is gearing up to persecute and condemn those who keep the seventh-day Sabbath.

Seibold suggested that Carson’s campaign would lead to the displaying of dirty laundry, and he noted that there has long been a conflict within the Seventh-day Adventist Church about how to come to terms with its own theology:

There are sharp differences among us how we regard such teachings. Some want to be forthright and forceful about them. The most blatant example was an offshoot church in Florida that put full-page ads in newspapers across the country explaining in painful particularity our Papal enemy and anticipated persecution, while erecting billboards blaming the antichrist for changing the Sabbath to Sunday. Those who are sending out millions of pulp-paper copies of [Ellen White’s] The Great Controversy fall into the same category…

Another group can’t bring themselves to discard any detail of The Great Controversy scenario, but they wince when it’s displayed in its nakedness. They’d say it’s a matter not of what we believe, but how we present it. Persecution by Roman Catholics is going to happen, but that’s the meat of the message, an advanced truth, and we shouldn’t reveal it to people until they’ve digested the milk… No, we’re not anti-Catholic, they say, just distrustful of Catholicism, and they hope that others will be able to understand this nuance.

There are others in our denomination whose faith doesn’t rely on these frightening prophetic narratives. These people love the Seventh-day Adventist church, too (although those in the previous two categories might dispute that), but see these ideas as leftovers of our 19th-century past. They believe that Jesus will return, but reject the idea that these fearful prophetic scenarios are essential truths. Just as other Christians have left behind their anti-Catholic or anti-Semitic prejudices, so must we.

The dynamic Seibold describes seems to mirror what often happens within a faith. There are fundamentalists who insist on literal readings of church rules, narratives, and dogma, and those who yearn to reform and modernize.

Seibold notes that he doesn’t know where “Carson comes down on any of these matters.” (Carson has approvingly referred to “prophecy” and the coming Sabbath “persecution.”) But Seibold appears to welcome the opportunity presented “when David Corn reveals our official paranoia,” for he sees this moment as a chance for the church to confront what he calls “the curious to downright nutty” aspects of Seventh-day Adventist teachings. He concedes that “for a century and a half we’ve been calling the Papacy the antichrist, the beast, and the whore of Babylon. We’ve described other Protestants as Babylon and apostate Protestantism.” He writes:

It is also true that stories about the Papacy’s plan to persecute those of us who worship on Saturday are a solid part of the writings of our 19th century prophet [Ellen White]. And yes, a substantial number of our people accept every word of that account as though it were history written in advance.

Seibold contends that the dark and paranoid aspects of Seventh-day Adventism need to be exorcised: “There are many in the Seventh-day Adventist church who see these stories as remnants of a frightened, nativist past.” And he believes that “this accusatory eschatology has distracted from the work of the gospel, and from bringing blessings to the world.” (He adds, “we have a bragworthy record of merciful work through our hospitals, disaster relief agencies, and schools.”)

If Carson does adhere to the church’s paranoid and accusatory (as Seibold puts it) worldview that depicts Catholics and Sunday-worshipping evangelicals as spiritual foes in league with the Antichrist, voters might have a legitimate interest in knowing the details. In an appearance at a 2013 religious event, Carson did provide a clue as to where he stands, declaring that one of the positive elements of Seventh-Day Adventism is that “we believe in the entirety of God’s word. We don’t pick and chose one part and say, ‘Well, now that part’s irrelevant and this part we’ll take.”

Seibold, naturally, is more concerned about the impact of Carson’s candidacy on his church than his church’s impact on Carson’s politics and policies. Yet he insists that Carson’s presidential endeavor justifiably raises questions about the church that ought to be addressed. “Ours is not a broad church, but a divided church,” Seibold writes, “and Dr. Carson’s candidacy may contribute to exposing that division… Right now, I don’t think any of us are sure how to resolve our past beliefs into a peaceful present, much less plan together for a continuing productive future. Pray for us.”

I am not sure my prayers would help the church much, as more reform-minded Seventh-day Adventists push it to confront these internal demons. But it hardly seems untoward to ask a candidate who trumpets his faith a few questions about that faith and what it might mean should he become the most powerful person in the land.