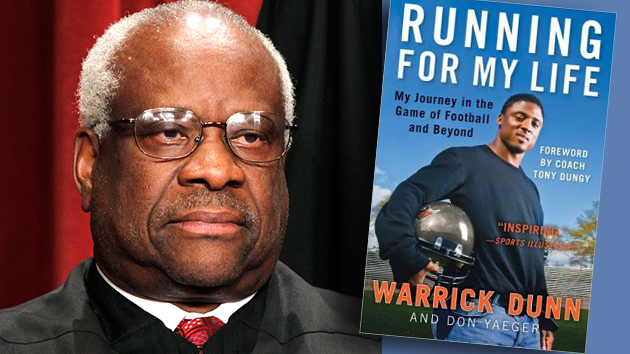

Justice Clarence ThomasSidney Davis/AP

For years, critics alleged that Justice Clarence Thomas was hiding behind his conservative compatriot, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, as a way of disguising a lack of intellectual heft or qualifications to be on the bench. Exhibit A has been the fact that it’s been a decade since Thomas asked a question during oral arguments. But today, in a courtroom still draped in black to honor Scalia, Thomas came out of that shadow to prove those critics wrong.

Thomas didn’t just ask one question—he asked many questions this morning and, in doing so, completely changed the direction of the oral arguments. In Voisine v. US, a somewhat obscure criminal case involving domestic violence and gun rights, the court is considering a case that could make it easier for people convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence offenses to keep their gun rights.

In 1996, Congress passed the Lautenberg Amendment to the Gun Control Act, which instituted a lifetime ban on gun possession for people convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence offenses. During most of the oral arguments this morning, lawyers and justices alike focused on the minutia of the definition of “battery,” as Congress might have intended it under the law. Then Thomas stepped in and raised a much larger constitutional question that might once have been asked by Scalia.

The oral arguments in the case appeared to be wrapping up early. Ilana Eisenstein, the assistant solicitor general, said to the justices, “If there are no further questions,” long before her time had run out. Then Thomas shocked the courtroom by asking her whether she could think of any other example where a misdemeanor criminal conviction could deprive an American citizen of a constitutional right for a lifetime—in this case the right to own a firearm, “which at least as of now is still a constitutional right,” he quipped.

The question came directly from an amicus brief filed in the case by the Gun Owners of America, which weighed in to support the two petitioners, a pair of men from Maine who’d been prosecuted under the federal law for possessing firearms after being convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence crimes.

The questions from Thomas left Eisenstein, who had looked about ready to sit down, a bit stumped—or perhaps just stunned because of their source. Thomas continued to press her, asking whether a misdemeanor conviction could deprive other people of other constitutional rights, perhaps under the First Amendment. “Let’s say that a publisher is reckless in the use of children, and what could be considered indecent displays,” he posited in a deep booming voice rarely heard in the chamber. “”Let’s say it’s a misdemeanor. Could you suspend that publisher’s right to ever publish again?”

The question elicited gasps and sent reporters, who’d decided to sit out the sleepy case in the press office, running upstairs to the courtroom to see if more words would emerge from the normally silent justice. It was also so provocative that Justice Stephen Breyer, who frequently chats with Thomas during arguments, also jumped in to press the issue, asking Eisenstein whether the court’s decision in the controversial case, District of Columbia v. Heller, might, in fact, create a problem for the government’s case in defending the Lautenberg Amendment. Heller—“with which I disagreed,” noted Breyer—is the 2008 case in which the court, for the first time, recognized an individual’s right to own firearms and which overturned DC’s strict gun control law.

Eisenstein concluded that Congress could not deprive a publisher of its First Amendment rights because of a misdemeanor crime, and that the law at issue in the case did not fully deprive defendants of their Second Amendment rights, either. States, she said, could still use their pardon power to restore gun rights to misdemeanants deemed worthy to get them back. She also pointed out that the petitioners in the case hadn’t raised the constitutional question in their filings themselves, so it wouldn’t necessarily be appropriate for the court to go there.

Thomas has always said he doesn’t ask questions during oral arguments because he’d prefer to listen—a habit he developed long ago in school, when he was handicapped with a Gullah accent that made his speech difficult for people to understand. Even so, the questions today from Thomas completely changed the nature of the arguments, showed him to be a powerful speaker, and defied the racist stereotypes about him. They illustrated why the court’s lone African American justice ought to pipe up more often. However he made his way to the court, Thomas has never been a Scalia flunky, and this morning he demonstrated he has a thoughtful, if extremely conservative, approach to bring to issues before the nation’s highest court. Perhaps in Scalia’s absence, we won’t have to wait another decade to hear more from him.