Supreme Court Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ruth Bader GinsburgPablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

Research going back to the 1970s shows definitively what women have long understood intuitively: Men have a hard time letting women talk without interrupting them—frequently. Apparently, not even holding one of the most powerful posts in America spares women from this irritating phenomenon.

Oral arguments at the Supreme Court can be brutal episodes of verbal warfare. Lawyers arguing their cases often can’t finish a sentence without a justice challenging their premises or changing the subject, and the justices even argue among themselves from the bench. A new analysis by Adam Feldman, author of the legal blog Empirical SCOTUS, attempted to quantify this phenomenon by examining this term’s oral arguments to determine which justices get interrupted the most by their colleagues, and which of those justices were also doing the most interrupting. The results were sadly predictable.

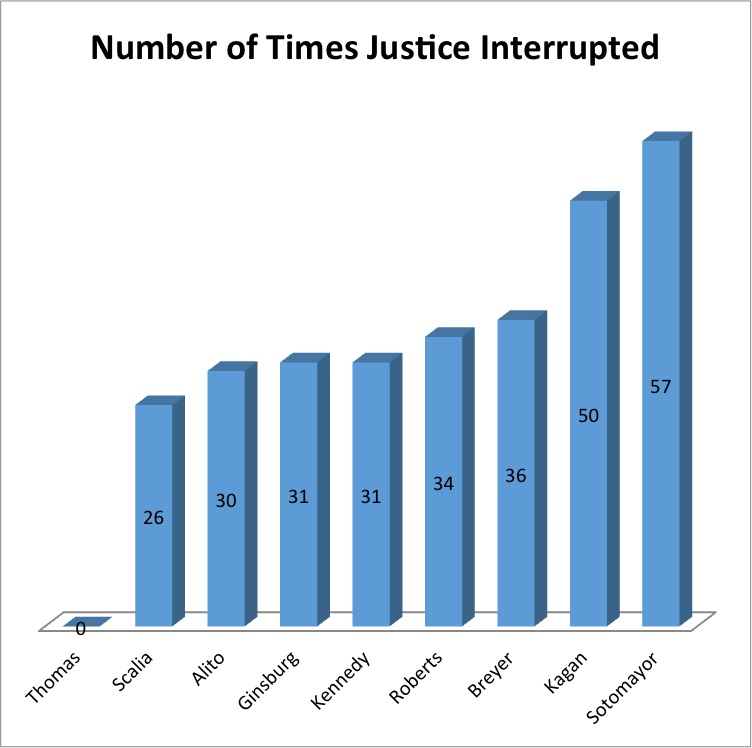

Men on the court spent a lot of time interrupting the two youngest female justices, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor. Sotomayor was interrupted 57 times during arguments, while Kagan got cut off 50 times. The next most-interrupted person on the list was Justice Stephen Breyer, who got interrupted 36 times—more than 35 percent less than Sotomayor, despite his habit of long, and sometimes impenetrable, hypothetical streams of consciousness from the bench.

Just who is doing all that butting in? Well, it’s not the other female justices. The most aggressive conversationalist by far was Justice Anthony Kennedy, the inveterate swing voter, who cut off his colleagues 57 times. He tends to ask a lot of questions of lawyers on both sides of a case. The person he most interrupted was Sotomayor, with 13 interventions. He also held the record for most frequently cutting off the venerable 83-year-old Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (13 times), whose halting and quiet speech her colleagues seem mostly reluctant to disturb, despite her gender. Justice Antonin Scalia might have been expected to score higher on the interruption scale, but sadly didn’t live long enough to finish out the term’s arguments.

One person Sotomayor and Kagan didn’t have to fear an intrusion from was Justice Clarence Thomas, who never interrupted or got interrupted; he spoke but once, an episode so rare and shocking that no one was going to step on his toes.

Why is it that even the nation’s most powerful female judges still can’t get a word in edgewise without their male colleagues cutting them off? Feldman has a theory. In an email, he suggests that because Kagan is the court’s most junior member, she “tends to be deferential” to her more senior colleagues. Sotomayor, meanwhile, has a tendency to start thoughts without finishing them. (That’s a problem Ginsburg doesn’t have; she also tends to be the first justice out the gate to ask a question during oral arguments, setting up the later confrontations.)

“The male Justices (Thomas excluded) also appear more aggressive in their approaches than either Kagan or Ginsburg,” Feldman says. “Sotomayor will assert herself but she doesn’t always follow through.” Feldman posits that because of the “history of the Court as a male-dominated institution that only recently (in its history) had a female confirmed,” it’s not immune to the same gender dynamics feminist scholars have been documenting in other, less lofty settings over the past 40 years.