Noclip/en.wikipedia

Should domestic abusers who get convicted of minor domestic-violence charges get to keep their right to own guns just because their crimes were merely reckless, as opposed to premeditated? That’s more or less the question the Supreme Court was considering in Voisine v. US, a somewhat obscure case that was languishing on the court’s docket as one of the last cases decided of the term. In a 6-2 opinion written by Justice Elena Kagan, the high court answered that question with a muted “no.”

The case challenges a 1996 amendment to the federal Gun Control Act, sponsored and named after the late New Jersey Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D), that barred people convicted of misdemeanor domestic-violence offenses from owning firearms. Violating the law carried a federal felony charge with a 10-year maximum sentence attached. The law was a triumph for women’s advocates because it recognized that people guilty of domestic violence were rarely charged with felonies and banned from gun ownership, and that there was a documented relationship between domestic violence and gun homicides. The law was designed to keep guns out of the hands of those perps, even when they’d only been convicted of misdemeanors.

Over the past 10 years, the gun lobby and some criminal defense groups have made a fairly concerted attack on the Lautenberg Amendment on various fronts to weaken its reach and try to return gun rights to batterers. Voisine is the third such case the court has heard since 2009. The latest defendants to take on the law are Stephen Vosine and William Armstrong III, neither of whom are model citizens. Voisine has a long track record of beating up his significant others. He pleaded guilty to assaulting his girlfriend in 2003, and was convicted again of assaulting a girlfriend in 2005.

After receiving an anonymous tip, federal authorities discovered that Voisine had shot and killed a baby bald eagle. They confronted Voisine about the shooting and he turned over a rifle. During a background check, federal authorities discovered his 2003 domestic-assault conviction. In 2011, he was prosecuted both for killing an endangered bird and for illegally possessing a gun after his prior domestic-violence conviction. He pleaded guilty—but reserved his right to appeal—and was sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

His co-plaintiff, Armstrong, who is also from Maine, was convicted in 2002 and 2008 on a misdemeanor domestic-assault charges for beating his wife. Two years later, Maine police discovered six guns in his possession when they searched his house for marijuana and drug paraphernalia. He was subsequently charged with illegal gun possession and sentenced to three years’ probation.

The lower courts have consistently upheld their convictions, but the Supreme Court vacated the sentences in 2014 and sent them back to the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals for reconsideration, to ensure that the crimes for which Armstrong and Voisine had been prosecuted were misdemeanor domestic-violence offenses as defined by the federal law. States can choose how to define a crime, and in Maine, the state law defined a misdemeanor domestic-violence offense as one that included crimes committed in the heat of passion—i.e., reckless actions—as opposed to premeditated ones, which are considered more serious.

In some cases, a reckless crime might not even result in a serious injury, but only “offensive touching.” The federal law’s definition of the required misdemeanor isn’t exhaustive; it doesn’t talk about a perpetrator’s motivation for an assault in defining domestic-violence crimes. But the appellate court decided that Maine’s definition of a “reckless assault” still met the requirements of the Lautenberg Amendment and could trigger the lifetime ban on gun ownership.

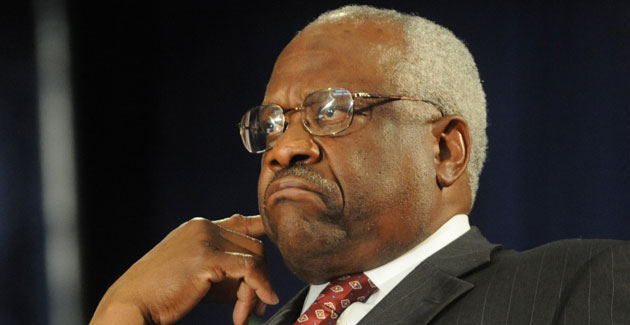

The Supreme Court agreed. It weighed a host of different scenarios to try to narrow down the definition of “reckless,” offering up various hypotheticals. A dissenting Justice Clarence Thomas boiled these down to “The Angry Plate Thrower” versus the “Soapy-Handed Husband,” to illustrate the difference between the use of force in a situation when someone who throws a plate in anger near his wife, even if it doesn’t hit her, and someone with soapy hands who “loses his grip on a plate, which then shatters and cuts his wife.” The soapy handed husband could clearly keep his guns, while the plate thrower could not, according to the majority in the ruling against Voisine.

Domestic-violence advocates had feared that a ruling for Voisine and Armstrong could reopen a loophole in the nation’s gun laws that the Lautenberg Amendment was supposed to close. They provided some pretty chilling examples of the types of behavior that, if prosecuted, could have become exempt from triggering the gun ban if Voisine and Armstrong had prevailed. The National Domestic Violence Hotline included in its brief examples from women calling its hotline to illustrate how “reckless acts” that don’t necessarily result in injury are usually part of a broader campaign to terrorize and control the victim. Among them were stories like these:

“My abuser has played Russian Roulette with me before and has pulled the trigger.”

“[My] husband once threatened me with a gun when I once wanted to stay up to finish baking Christmas cookies. He is a control freak, so he didn’t want someone to stay up if he was going to bed.”

“He shot a gun at my feet and someone called the police. [He] was arrested on violation of restraining order but gun charges were dropped.”

“[He] never fired the pistol, but he would sit on my chest and point it at my head. He would put it right next to my temple.”

In briefs in the case, women’s advocates argued that Congress intended for people such as Voisine and Armstrong to lose their gun rights specifically because the justice system has been so bad at prosecuting batterers. Historically, prosecutors have downplayed domestic-violence crimes. Convictions were rare, and even serious assaults were—and often still are—pleaded down to misdemeanor charges. As a result, the misdemeanor convictions often obscured how potentially dangerous the defendant really was, especially if he got his hands on a gun. Their arguments were apparently persuasive.

Only one group weighed in on the side of Voisine and Armstrong: Gun Owners of America, a gun rights group that believes the National Rifle Association is too liberal. Its lawyers, who filed an amicus brief in the case—the 10th such filing they’ve made in cases challenging the domestic-violence gun ban—argue a misdemeanor conviction isn’t sufficient grounds to deprive an American citizen of the right to possess a gun. The gun owners found a sympathetic voice in Thomas, who used the case to offer his first questions from the bench in a decade during oral arguments in February.

The oral arguments in the case appeared to be wrapping up early. Ilana Eisenstein, the assistant solicitor general, said to the justices, “If there are no further questions,” long before her time had run out. Then Thomas shocked the courtroom by asking her whether she could think of any other example where a misdemeanor criminal conviction could deprive an American citizen of a constitutional right for a lifetime—in this case the right to own a firearm, “which at least as of now is still a constitutional right,” he quipped.

The question Thomas raised prompted liberal Justice Stephen Breyer to chime in that his colleague might, in fact, have a point. They questioned whether, for instance, a publisher who’d done something wrong that resulted in a misdemeanor could lose his constitutional right to publish for life the way the gun owners in this case had been. Those questions might explain why the court took so long deciding what should probably have been an easy case given its precedent. In past cases, the Supreme Court hasn’t been too sympathetic to such arguments, and it ruled against the plaintiffs in similar cases that reached the high court in 2009 and again in 2014. But Thomas managed to persuade an unlikely ally to join him at least in part in his dissent: liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

In enacting the Lautenberg Amendment, Thomas writes, “Congress was not worried about a husband dropping a plate on his wife’s foot…Congress was worried that family members were abusing other family members through acts of violence and keeping their guns by pleading down to misdemeanors.” He argues that exempting people convicted of reckless batteries that did not include the intentional use of force—the husband who hits his wife with a plate because it slipped out of his soapy hands—would serve Congress’ intended purpose, but instead, the majority had gone too far, and ensured that “a parent who has a car accident because he sent a text message while driving can lose his right to bear arms forever if his wife or child suffers the slightest injury from the crash.” Sotomayor agreed with Thomas’s analysis of the “Soapy-Handed Husband” dilemma but declined to sign on to his Second Amendment tirade in which he inveighed against the majority for agreeing to allow a single minor reckless assault to deprive a citizen of an enshrined constitutional right to own guns. “We treat no other constitutional right so cavalierly,” he concluded.