President Clinton gestures while meeting with chief executive officers in the White House Cabinet Room on January 10, 1997, to discuss welfare reform. Ruth Fremson/AP Photo

Sometime last year, without any public announcement or debate, Gov. Phil Bryant of Mississippi made a decision that could disrupt the lives of thousands of his state’s poorest residents. The two-term Republican governor quietly reintroduced a three-month limit on food stamps for “able-bodied adults” between the ages of 18 and 49 who have no dependents. After three months of receiving federal food aid through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), they would have to prove they were working at least 20 hours a week. If they couldn’t, their food stamps would be cut off.

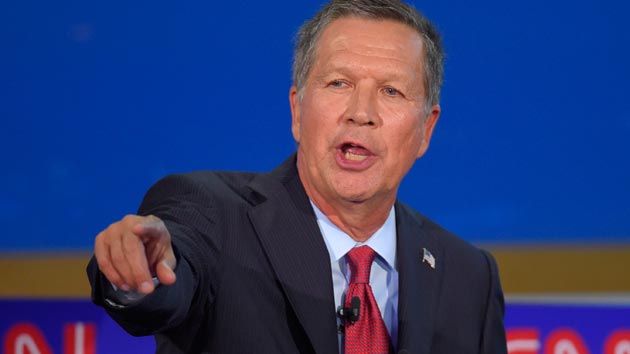

This time limit is an often overlooked section of the sweeping welfare reform bill that President Bill Clinton signed into law 20 years ago. The provision was added to a late version of the bill by Reps. John Kasich and Bob Ney, both Ohio Republicans. Some Democrats were appalled; Rep. Bill Hefner (D-N.C.) declared it the “most mean-spirited amendment” he’d seen in his 22 years on the Hill. But the amendment was debated in the House for only half an hour before being adopted. Clinton expressed “strong objections” to it, but he signed the final bill nonetheless.

The food stamp cutoff was in keeping with the bill’s core assumption—that pushing welfare recipients to get a job, no matter how menial, was the most effective way to end their dependency on public aid. Long-term studies eventually disproved the “get a job, any job” theory: Giving people new skills and education has proved more effective at lifting them out of poverty. But by that point, the logic of welfare reform had become entrenched across the political spectrum, especially among conservatives.

The 1996 law did grant states a large degree of discretion over how, and whether, the food stamp cutoff would be implemented. States with high unemployment could request a waiver from the time limit. Mississippi, for example, had received waivers for the last decade. Yet this year, six states have passed up the waivers, while others are no longer eligible due to rising employment rates. Across the country, between 500,000 and 1 million people will lose access to federally funded food assistance this year because of the newly introduced time limits.

The tension between the rhetoric of welfare reform and the realities of poverty is nowhere more evident than in Mississippi, which has the nation’s highest rates of food insecurity and poverty and its fifth-highest unemployment rate. By reinstating the SNAP time limit, Gov. Bryant said he wanted to “steer people to jobs.” Yet with unemployment rates rising above 10 percent in some Mississippi counties, few jobs exist. And the loss of SNAP, which averages about $5 a day, will leave many low-income residents hungry, says Matt Williams, research director at the Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative. “It’s the difference between having a meal every day until the end of the month and literally running on empty the last couple weeks.” The Mississippi Center for Justice estimates that more than 42,000 able-bodied adults disappeared from the state’s SNAP rolls in the first half of this year, about 7 percent of the Mississippians who’d been getting food aid.

The federal government offers additional funding to states that pledge to provide job training or workfare slots for every person facing the food stamp time limit. But only five states have made the pledge; Mississippi is not among them. As of last year, the state only planned to offer 1,391 workfare slots each month. Workfare and job training programs are expensive, explains Ed Bolen, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, and under the 1996 welfare reform law, states are not obligated to offer them.

The law does exempt people who are “mentally or physically unfit for employment” from the time limit, but many states don’t make much of an effort to check who meets that criteria. In 2014, Franklin County, Ohio, which includes Columbus, set up meetings for food stamp recipients facing the time limit. “They were brought in in very large groups, anywhere from 200 to 400 people…and basically told to go get a job,” recalls Lisa Hamler-Fugitt, executive director of the Ohio Association of Foodbanks. The sessions were “worse than cattle calls.”

Over the next year, her organization conducted a survey of 5,000 people subject to the cutoff. What it found contradicted the popular image of the food stamp recipient who could work but just didn’t feel like it. One in three “able-bodied” clients reported a physical or mental limitation, with a quarter saying their condition interfered with their daily activities. Nearly 13 percent said they were caregivers to a parent, friend, or relative. And 36 percent said they had a felony conviction, a common barrier to employment. The organization found that it was exceedingly difficult to place “able-bodied” clients in volunteer or training programs that would fit their requirements and restrictions; its 24 percent success rate was above average.

Earlier this year, Florida decided to go without waivers for its most economically distressed counties. Cindy Huddleston, an attorney at Florida Legal Services, thinks the public doesn’t really understand whom the food stamp cutoff affects. “If people realized [that these are] veterans, people with mental disabilities, people who have nowhere else to turn…they might feel differently.”