Imgorthand/iStock

About halfway through Glenn Beck’s 2010 “paranoid thriller” The Overton Window, his protagonist discovers a slide deck detailing a secret leftist plot to gradually subvert the American Way and take over the United States. The conspirators (who include the protagonist’s dad) are employing an insidious, if somewhat wonky, tactic. As Beck’s hero explains, “It’s called the Overton Window. My father stole the concept from a think tank in the Midwest; it’s a way of describing what the public is currently ready to accept on any issue, so you can decide how best to move them toward what you want.”

That’s a pretty good distillation of the Overton Window, a concept that’s suddenly gotten a lot of attention as Donald Trump and his allies have pushed the boundaries of acceptable political discourse. “On key issues, [Trump] didn’t just move the Overton Window, he smashed it, scattered the shards, and rolled over them with a steamroller,” National Review’s David French noted with a mix of dismay and admiration in late 2015. Trump’s disregard for mainstream conservatism has also emboldened his boosters on the extreme right. The day before he announced his run for Louisiana’s Senate seat, ex-Ku Klux Klan leader and Trump fan David Duke tweeted about squeezing through the Overton Window into a federal office. “If you want to radically shift the Overton Window, you need that far-right flank,” Richard Spencer, the white nationalist credited with coining the term “alt-right,” told Mother Jones.

As Trump continues to push policies and embrace figures that would have been anathema not so long ago, we’re about to see the Overton Window shift to accommodate the defenestration of progressivism. One area to pay close attention to is education, where Trump has a direct link to the origins of the Overton Window concept—and where the Trump administration will likely promote policies that would blow up public education as we know it.

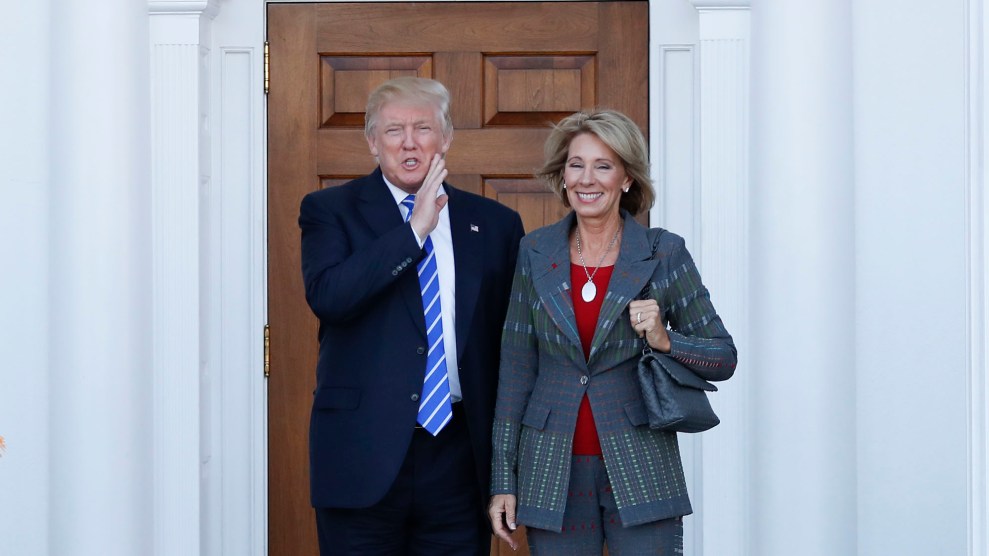

Trump’s connection to the Overton Window starts with Betsy DeVos, his pick for secretary of education. She’s married to Dick DeVos, heir to the multilevel marketing giant Amway and a leading bankroller of Republican and conservative causes and candidates in their home state of Michigan. The DeVoses have also been major funders of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a conservative think thank that has long pushed for deregulation, privatization, and weakening labor unions. (Dick DeVos has also served on the center’s board of directors.) The Mackinac Center is also the birthplace of the Overton Window.

The concept is named after its creator, Joseph Overton, the late senior vice president of the center. In the mid-’90s, Overton developed the idea to describe how a think tank might shift public opinion to consider ideas beyond the realm of conventional wisdom. Since politicians would not entertain these risky ideas for fear of rocking the boat, it was up to political outsiders and the public to nudge politicians toward “bolder” choices. In other words, any policy that might currently be considered too extreme for discussion may eventually be normalized through a series of gradual shifts in public opinion. According to the model, politicians rarely move the window. Arguably, Trump may not have personally shifted the window so much as climbed through an opening created by his base.

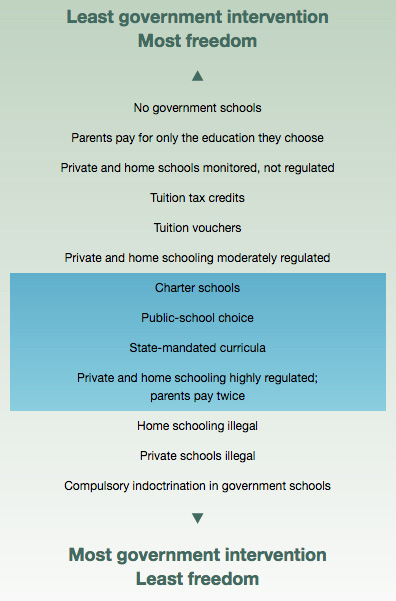

Unlike the big-government baddies in Beck’s novel, the Mackinac Center doesn’t conceal its efforts to shift the Overton Window toward “free market” solutions. (It even has an Overton Window Facebook page.) In its description of the concept, Mackinac places policies along a liberal-conservative continuum, with the left represented by “Most government intervention/Least freedom” and the right by “Least government intervention/Most freedom.” For example, on gun policy, the scale encompasses everything from no private ownership of weapons (least freedom) to no restrictions of any kind on weapon ownership (most freedom). When it’s applied to education policy, the scale ranges from “Compulsory indoctrination in government schools” to “No government schools”:

While any discussion of eliminating public schooling may currently seem outrageous, that could change as more states embrace the “reforms” outlined by the Mackinac Center. “Why is it that we educate children by having the government assign them to schools?” asked the center’s president, Joe Lehman, in an appearance on Beck’s show before describing how Mackinac has successfully challenged education policy in Michigan. “We’ve shifted that window up.” A Mackinac article on Overton’s legacy notes just how far he and his colleagues were able to move the state’s education policies: “Home schooling is here to stay, charter schools are well established, and school choice continues to gain ground. In fact, in some parts of Michigan it is now even possible to run for office on a platform that includes the Universal Tuition Tax Credit—another Overton innovation—a situation that was unthinkable just 10 years ago.” On the Overton scale, tax credits for education are just three steps away from the final goal: “No government schools.”

Which brings us back to Betsy DeVos. As my colleague Kristina Rizga explains, DeVos has spent decades trying to gut Michigan’s education system in the name of school choice. While she has not publicly called for an end to public education, DeVos has written about the need to “retire” and “replace” Detroit’s public school system. And she has pushed for aggressively expanding charter schools (with minimal oversight) and expanding the use of school vouchers to fund private and parochial schools—key steps on the Mackinac Center’s continuum.

Another sign the Overton Window is lurching rightward is the adoption of the language promoted by the DeVoses and Joseph Overton himself. In a 2002 speech at the Heritage Foundation, Dick DeVos advocated a shift in how conservatives talk about America’s schools. “‘Public schools’ is such a misnomer today that I really hate to use it,” he said. “I’ve begun to use the word ‘government schools’ or ‘government-run schools’ to describe what we used to call public schools because it’s a better descriptor of what they are.” At the time, you might have been hard pressed to find a prominent Republican politician willing to use such a loaded term. Fourteen years later, the president-elect is talking about our “failing government schools.”