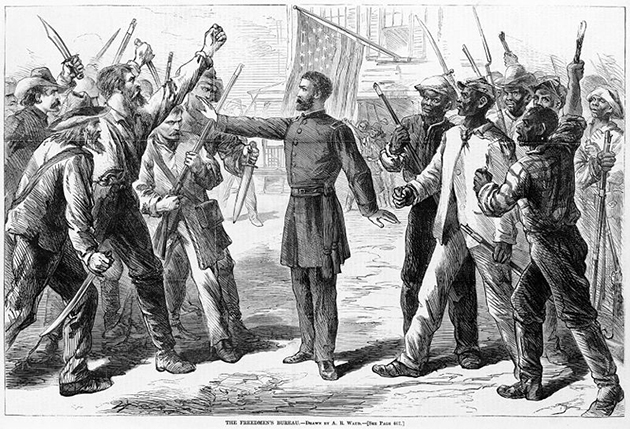

AR Waud, Harper’s Weekly/Library of Congress

People deal with political trauma in different ways. After the 2016 election, yuppies who once scoffed at preppers found themselves stockpiling canned goods. Barack Obama went kitesurfing. Hillary Clinton hiked in the woods. Hundreds of thousands of people began meeting in small groups—”for the first time in my life,” many told reporters—to organize a resistance. Some people bought bourbon, some people bought dogs, and I found myself reading about Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

In the years before the Civil War, Higginson, the abolitionist scion of a powerful Boston Brahmin family, had run for Congress, dabbled as a Unitarian minister, bankrolled John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, and even sustained a sword wound to his face while breaking into a Massachusetts jail to rescue a fugitive slave. He prayed for a great cleansing war to rid the nation of slavery and when it came, he cheerfully enlisted. Then, in the fall of 1862, Higginson embarked on one of the most radical projects in American history.

Placed in command of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the Union Army’s first all-black regiment, Higginson found himself at the epicenter of a social revolution. Under his eye, former slaves seized abandoned plantations, divided up the land and livestock, and built new civic institutions rooted in the idea of racial equality. The so-called Port Royal Experiment turned South Carolina’s low country into an incubator of black social and political culture—the tip of the spear of Reconstruction.

Higginson believed in the transformational nature of his work, but one evening in 1863, he peered with stunning clarity into the future. “Revolutions may go backwards,” he fretted in a diary entry that ought to be carved in granite, “and the habit of injustice seems so deeply impressed upon the whites that it is hard to believe in the possibility of anything better.”

I began reading about Reconstruction last winter, at a moment when eight frustrating years of progress, compromise, and apathy were culminating in a ferocious resurgence of white nationalism. It felt as if something was missing from what I’d learned about American history. Evidently I was not alone.

“I’m reading a ton of history books about Reconstruction,” MSNBC’s Chris Hayes told the New York Times in March. “In fact, it’s basically all of what I’m reading.” Slate‘s Jamelle Bouie chronicled his own reading of W.E.B. Du Bois’ “vital” doorstop of a study, Black Reconstruction, and in the process drew a direct line between President Donald Trump’s nativist campaign and the Redemption movements of the 1870s—in which racist whites seized power in parts of the South through violence and massive voter suppression, effectively putting an end to Reconstruction.

Long neglected by the historical-industrial complex, Reconstruction is inching toward the respect it deserves. A revisionist biography of Ulysses S. Grant cracked the bestseller list last fall and sales of Columbia University historian Eric Foner’s 30-year-old urtext, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, have ticked up since the election. Henry Louis Gates Jr. is developing a Reconstruction series for PBS. Ava DuVernay’s Oscar-nominated documentary, 13th, traced the rise of mass incarceration to its roots as a slavery substitute after the war. Actor Mahershala Ali couldn’t save Free State of Jones, but Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Amazon are developing a movie about a Klan-hunting Army unit in South Carolina. Next year marks the sesquicentennial of the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson—a delusional, power-hungry, self-appointed savior of the white working class whose attempt to circumvent traditional party politics ended in personal and political ruin. Don’t knock yourself out trying to find a parallel.

The quality that made Reconstruction an afterthought in classrooms and our national memory is also what makes it so essential right now. It’s “basically the story of a successful terrorist campaign & it’s hard to know what to do with that,” Hayes tweeted. The arc of the moral universe didn’t bend to fit the goals of Reconstruction. It broke, and we’re still picking up the pieces.

No scholar has captured the promise of Reconstruction and the ferocity of its destruction as clearly and consistently as Eric Foner. The Atlantic‘s Ta-Nehisi Coates, who hosted his own Reconstruction book club a few years back, called America’s Unfinished Revolution “my Bible” on the subject. So, on a weekday afternoon in April, I made a pilgrimage to New York City’s Upper West Side to talk to Foner about his boomlet of popularity.

Foner’s office is a shrine to the era. Its “history tchotchke section” includes an Andrew Johnson Pez dispenser lingering threateningly amid bobblehead dolls of Thaddeus Stevens, Abraham Lincoln, and Salmon P. Chase. On his bookshelf, a bust of Du Bois props up a copy of The Third Reconstruction, the Reverend William Barber’s 2016 manifesto about his North Carolina “Moral Mondays” movement.

Reconstruction, as Foner points out, tends to come back into vogue during times of political transition. “People get very excited when they discover that there was this moment when actual radical change seemed possible,” he says. “I think that’s great! I think it’s inspirational, actually, which is one of the reasons that I’m so interested in it. It shows you that ordinary people in very difficult circumstances can actually take dramatic action to change society for the better.”

“Of course, it’s overthrown,” he adds.

Before Foner and his contemporaries took a crack at it, the Reconstruction story had been shaped by successive generations of historians who gave Southern propaganda a gloss of historical authority. These scribes villainized the black politicians and the “Radical Republican” lawmakers who pushed Reconstruction-era reforms through Congress. “Carpetbaggers,” as the Northerners who moved south to work in politics and business were portrayed, became known as corrupt bandits rather than as the dedicated idealists that many were. In this version of the narrative, Southern whites were the victims, and the Redemption (an exercise in Frank Luntz-ian branding if ever there was one) had an almost purifying effect.

Foner, like Du Bois before him, discovered a profoundly different story. Corruption was not uncommon in the 1870s, but the state and local Reconstruction governments that took root in the South were far more equal and democratic than anything that had existed in the United States before, and for a long time since. Black communities were, for the first time, governed by black leaders. Thousands of former slaves took government jobs; they were elected sheriffs, served in Congress, and ran local party organizations called Union Leagues. In 1868, South Carolina had a majority-black House of Representatives. Newspapers flourished. The idea of who and what government was for changed dramatically.

This new Southern society did not collapse from within. It was violently overthrown by the Democrats—the original pro-slavery party. Black Republican voters were massacred, and their lawmakers were assassinated. The federal government intervened for a time, but the North’s appetite for resistance eventually faded, and that was the end of that.

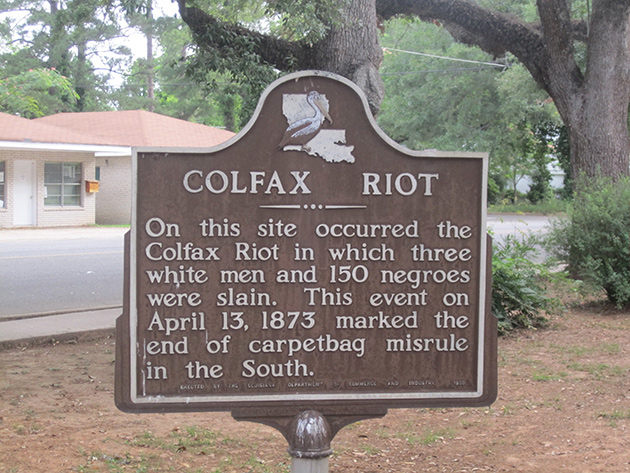

One event in particular sums up both the reality of Redemption and the way its memory has been warped. In 1873, after the Democrats lost the Louisiana governor’s race, a group of white paramilitaries that would later be known as the White League set out to seize local offices by force. They killed about 150 black citizens during a rampage in the town of Colfax. The state placed a plaque at the site in 1950. The “Colfax Riot,” it explains, “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

Change comes slowly. In April, protected by police snipers, city workers in bulletproof vests removed a divisive New Orleans monument to the 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, in which 5,000 White League members—still sore about that 1872 election—seized control of Louisiana’s capital for three days. “United States troops took over the state government and reinstated the usurpers,” read the offending plaque, “but the national election of November 1876 recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state.”

Foner’s battle with the Southern historians is largely over (advantage: Foner), but Reconstruction still struggles for respect. One reason, he says, is that it’s overshadowed by the Civil War. And then there’s the tricky matter of national identity. Borrowing an argument from a Yale colleague, Foner recalls William Dean Howells’ famous criticism of The House of Mirth, a 1906 play adapted from the Edith Wharton novel: “What the American public always wants in the theater is a tragedy with a happy ending.”

“Reconstruction doesn’t have a happy ending,” Foner says. “It’s hard to assimilate into an onward and upward vision of America that says things have been getting better and better all the time. Reconstruction doesn’t fit the upward trajectory.”

No, it’s more as though American history were Groundhog Day, and we’ll keep repeating the cycles of Reconstruction and Redemption until we can figure out how to live together. But for all of Foner’s willingness to see the era’s contemporary echoes, he blanches at the idea that we should view regression as inevitable. “People who lived through Reconstruction did not know Redemption was coming,” he says. “They were operating on the basis that this was happening, that this was gonna be permanent, that these rights were going to be there, and thinking about what to do with them. You can’t make Reconstruction purely a question of failure, and you can’t make it purely a question of why did it fail.”

It is indeed worth considering what survived: Colleges, churches, and other civil institutions born in that utopian moment are still going strong. The 13th Amendment’s ban on slavery was never seriously challenged. The 14th Amendment—150 years young in 2018—is a cornerstone of modern politics. The Justice Department, formed to combat Southern white terrorism, would some 90 years later become the vehicle by which the “Second Reconstruction” was enforced, and (Jeff Sessions notwithstanding) it may yet be the vehicle to drag America out of its latest Redemption.

Before we part ways, Foner tells me how Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s story ends. In 2000, before Bill Clinton left office, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt read Foner’s book and decided to give him a call. Babbitt considered it a travesty that the National Park Service had dozens of sites focused on the Civil War but hardly any dedicated to Reconstruction. Babbitt wanted Foner’s input on where to start. The professor didn’t hesitate: Beaufort, South Carolina—home of Higginson and the Port Royal Experiment.

The Park Service seemed amenable—that is, until a group called the Sons of Confederate Veterans pushed back, condemning the government’s effort to “ignore the corruption and cruelty, which victimized so many South Carolinians.” The Redeemers, once more, appeared to have the last word. But the idea made a comeback toward the end of the Obama administration, and the Park Service tapped a pair of historians to recommend how best to incorporate Reconstruction into the monument list.

The project took on new after the election. Who knew what the future held under a budget-slashing admirer of Andrew Jackson? So in December, Foner and the Park Service’s consulting historians penned a New York Times op-ed asking the agency to get a move on. The city of Beaufort chimed in, too, and Obama signed off on the Port Royal monument with just eight days left in his term.

On the eve of Trump’s inauguration, it was a fitting memorial to progress. Perhaps it should be a warning, too.

This article has been revised.